⑴

So, what about colors ? We've already started looking at pictures. Well, how are those pictures be it emojis or anything else, represented ? One of the most common ways is just with RGB - - red, green and blue. It turns out that if we just keep track of how much red should be on the screen and how much freen, and how much blue, combined together that gives up every color of the rainbow from white to black and everything in between. So how do we represent an amount of red and green, and blue ? Well, frankly, just with three different numbers.

And this is how computers typically represent colors. Every one of the dots on your computer screen or your phone screen is called a pixel. And every single dot underneath the hood has three numbers associated with it, so three numbers, three numbers, three numbers for every little dot. And those three numbers, together, say how much red, green and blue should the device display at that location.

So, for instance, if you had a dot on your screen that said, " use this much red, this much green, this much blue ", because each of these numbers, I'll tell you, are one byte or eight bits, which means the total possible values is 0 to 255.

Let me just ballpark that the 72, it feels like a medium amount of red because it's in between 0 and 255, 73 is a medium amount of green, and 33 of blue is just a little bit. So if you combine a medium amount of red, green and a little bit of blue, anyone want to guess what color of the rainbow this is ? It's a little more yellow than it is brown.

But if we combine them, it looks a little something like this.

⑵

We've seen these numbers before, 72, 73, 33 represented what ? So it meant " Hi! " but here I am, claiming that yellow. How do you reconcile this ? Well, at the end of the day, this is all we have 0's and 1's, whether you think of them as numbers or letters, or even colors now. But it depends on the context. So if you've received a text message or an email, odds are the pattern of 0's and 1's that the computer is showing you are going to be interpreted as text because that's the whole point of a text message or an email. If, though, you opened up MacOS's or iOS's or Windows's or Android's calculator app, the same pattern of 0's and 1's might be interpreted as numbers for some addition, or subtraction, or whatever. If you open the same pattern of 0's and 1's in Photoshop, like a graphics program, they're going to be interpreted, in that context, as colors. So context matters.

⑶

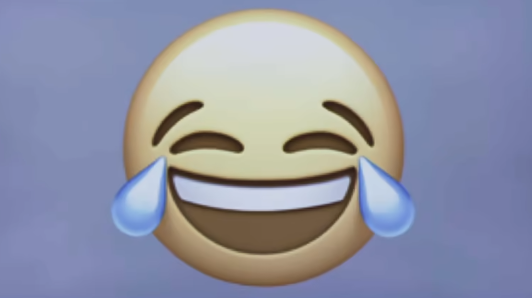

And you can actually see these dots, these pixels on the screen.

Let me zoom it, zoom it.

And here we have it, just with this emoji, which, at the end of the day, is a picture that someone at Apple, in this case, drew.

And you can see - - if you really room in, or take your phone or TV, and really put it close to your face, you'll see all of these dots, depending on the hardware.

And each of these dots, these squares, is storing 24 bits or 3 bytes, 24 bits, 24 bits, 24 bits. And that's why, dot, dot, dot, if you're got a photograph, for instance, that's three megabytes, which is 3 million bytes, well, odds are these's 1 million pixels there in because you're using three bytes per pixel to represent each of those colors. That's a bit of an oversimplification, but that's why images and photos are getting bigger and bigger nowadays. Because we're throwing even more pixels into the file.

⑷

.How could you represent music, digitally, using just 0's and 1's, or numbers, really ? Any instinct, whether a musician or not ? Yeah, we can just represent notes by a number. So, A is some number, and B is some number. And maybe sharp or flat is some other number. So, one number to represent the note, itself, the sound or the pitch, one other numbers to represent the duration. In the context of piano, how long is the human holding the key down ? And maybe I can think of a third, the loudness. How hard has the person played that note ? So minimally, with three numbers, you could imagine representing music, as well. And indeed, that's very well might be what computers are doing when you listen to sound. What about video ? How could you represent videos, as well ? Yeah, many images. So, if you've ever produced a film or looked at some of the fine print, 30 frames per second, FPS, or 29 frames per second, is just how many pictures are flying across the screen. But that's really all a video file is on a computer, lots of pictures moving so quickly in front of us that you and I, our brains interpolate that as being actual motion. And, in fact, from yesteryear, motion pictures, it's like pictures that are giving the illusion of motion, even though there's only 30 or so of them flying across the screen.

⑸

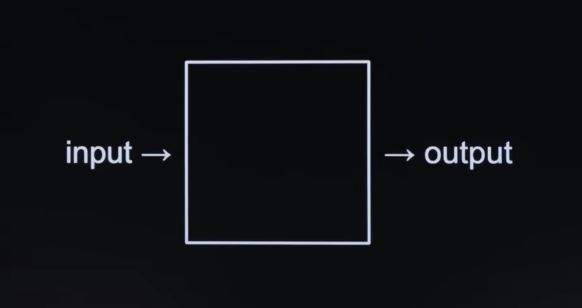

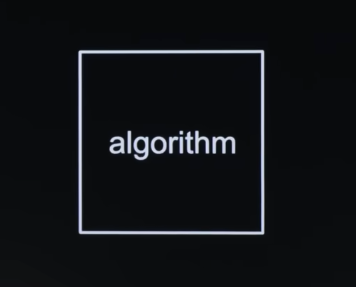

So, we have a way, now, to represent information, both as input and output, whether it's numbers, letters, images, anything else.

Let's now focus on what's inside of that black box, so to speak, wherein we have algorithms, step - by - step instructions for solving some problem. Now, what do I mean by " algorithms " or " step - by - step instructions " ?

Well, maybe, if we were to turn this into code, and that's how we'll connect the dots, ultimately, today. Code is just the implementation, in computers, of algorithms. An algorithm can be something we do in the physical world, Code is how we implement that exact same idea, in the context of a computer, instead.

And here, for instance, is a very common application inside of a computer for your context. This is the iOS version of the icon. And, typically, if you click on that icon,

you"ll see something like all of your contacts here, typically, alphabetical, by first name or last name. And your phone or computer lets you often search for someone's name at the very top. And it will autocomplete, and it'll be pretty darn fast. But it'll be pretty darn fast because the programmers who implemented that application are looking for someone quickly for you.

⑹

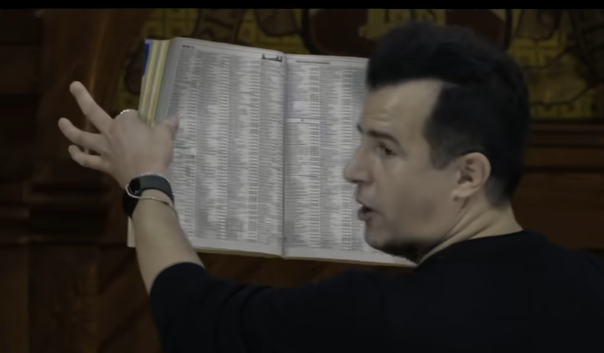

Now I can do this old school style, whereby we have one of these things from yesteryear, an actual phone book. So, in a physical phone book, you might have 1000 pages. And on every page are a bunch of names and a bunch of numbers. And as I flip through this, I could look for someone specific. So suppose I want to call John Harvard, who's the first name starts with a " J ". Well, I could just turn page by page, looking for John Harvard. And if he's not there. I keep turning and turning. So this is an algorithm. I'm stepping through the phone book, one page at a time. Is it correct, this algorithm, assuming I'm looking down ? I mean, it's stupidly slow because why am I wasting my time with the A's, and the B's and the so forth ? I could probably take bigger bite out of it. But it is corret. And that's going to be one of the goals of writing code, is to solve the problem, you care about correctly. So correctness goes without saying, or else what's the point of writing the code or solving or implementing the algorithm ? Well, let me at least speed things up. So instead of one page at a time, so 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, and so forth. It's a little hard to do, physically, but it sounded faster. It was twice as fast, theoretically, but is it correct ? Yeah, I might miss John Harvard because, just by accident, he might get standwhiched between two pages. But do I have to throw the algorithm out altogether ? Probably not. Once I reach the " K "section, which is past the " J " section。 I could double back at least one page, and just make sure I didn't blow past him completely. So that is twice as fast, because I'm going two pages at a time plus one extra step. So it's still an improvement. So the first algorithm, worst case, if it's not John but someone whose name starts with " Z " that might take me a full 1000 steps. The second algorithm is just 500 steps because I'm going two pages at a time plus one, in case I have to double back but that's in the worst case. But most of us in the yesteryear, and what Apple, and Google, and others are actually doing is, in software or here physically. We're typically going, roughly to the middle. Especially if there's no cheat sheet on the side, like A through Z. I'm just going to go to roughly the middle. And oh, here I am not surprisingly, in the " M " section.

But what do I know ? If this is the " M " section, where is John Harvard ? So, clearly, to the left alphabetically. And so here is where we can take a much bigger bite out of the problem. We can really divide and conquer this problem by tearing the problem (book) in half, throwing half of it away, 500 pages away, leaving me with a smaller problem, half as big, that I can really just now repeat.

So I go, roughly, here and now I'm in the ' E " section. So I went a little too far back. But what do I now know ? If this is the " E " pages, where's John ? So, now he's to the right. So I can tear the problem in half again, throw that 250 pages away. And now I've gone from 1000 to 500 to 250 pages. Now I'm moving because the first algorithm was one page at a time, second was two, This is hundreds of pages at a time. And if I go, roughly, again to the middle, roughly to the middle, roughly to the middle, hopefully, I'll find John Harvard on one final page. So that invites the question I would think , if the phone book does have 1000 or so pages, how many times can I divide the problem in half to get down to one last page ? So it's roughly 10. And the quick math is 1000 goes to 500 to 250 to 125 to 67 something. So we have to deal with rounding issues, eventually. But assuming we work out the math, it's, roughly 10 page tears. And that's crazy faster than 1000 pages and still faster than 500 pages, so it's fundamentally better.