作用域在所有权(ownership)、借用(borrow)和生命周期(lifetime)中起着重要作用。也就是说,作用域告诉编译器什么时候借用是合法的、什么时候资源可以释放、以及变量何时被创建或销毁。

15.1 RAII

Rust 的变量不只是在栈中保存数据:它们也占有 资源,比如 Box<T> 占有堆(heap)中的内存。Rust 强制实行 RAII(Resource Acquisition Is Initialization,资源获取即初始化),所以任何对象在离开作用域时,它的析构函数(destructor)就被调用,然后它占有的资源就被释放。

这种行为避免了资源泄漏(resource leak),所以你再也不用手动释放内存或者担心内存泄漏(memory leak)!下面是个快速入门示例:

// 15.1节 RAII

fn create_box() {

// 在堆上分配一个整型数据

let _box1 = Box::new(3i32);

// `_box1` 在这里被销毁,内存得到释放

}

fn main() {

// 在堆上分配一个整型数据

let _box2 = Box::new(5i32);

// 嵌套作用域:

{

// 在堆上分配一个整型数据

let _box3 = Box::new(4i32);

// `_box3` 在这里被销毁,内存得到释放

}

// 创建一大堆 box(只是因为好玩)。

// 完全不需要手动释放内存!

for _ in 0u32..1_000 {

create_box();

}

// `_box2` 在这里被销毁,内存得到释放

println!("Hello Rust");

}

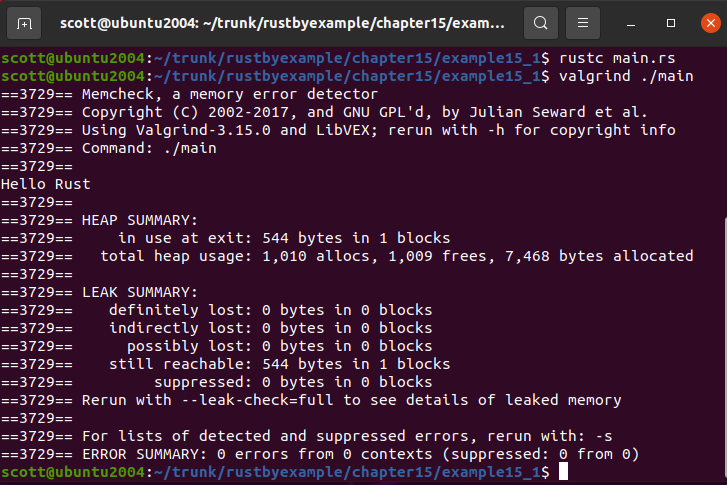

// rustc main.rs

//当然我们可以使用 valgrind 对内存错误进行仔细检查:

// valgrid ./main

// ./main当然我们可以使用 valgrind 对内存错误进行仔细检查:

(Ubuntu2004环境)

scott@ubuntu2004:~/trunk/rustbyexample/chapter15/example15_1$ rustc main.rs

scott@ubuntu2004:~/trunk/rustbyexample/chapter15/example15_1$ valgrind ./main

==4513== Memcheck, a memory error detector

==4513== Copyright (C) 2002-2017, and GNU GPL'd, by Julian Seward et al.

==4513== Using Valgrind-3.15.0 and LibVEX; rerun with -h for copyright info

==4513== Command: ./main

==4513==

Hello Rust

==4513==

==4513== HEAP SUMMARY:

==4513== in use at exit: 544 bytes in 1 blocks

==4513== total heap usage: 1,010 allocs, 1,009 frees, 7,468 bytes allocated

==4513==

==4513== LEAK SUMMARY:

==4513== definitely lost: 0 bytes in 0 blocks

==4513== indirectly lost: 0 bytes in 0 blocks

==4513== possibly lost: 0 bytes in 0 blocks

==4513== still reachable: 544 bytes in 1 blocks

==4513== suppressed: 0 bytes in 0 blocks

==4513== Rerun with --leak-check=full to see details of leaked memory

==4513==

==4513== For lists of detected and suppressed errors, rerun with: -s

==4513== ERROR SUMMARY: 0 errors from 0 contexts (suppressed: 0 from 0)

scott@ubuntu2004:~/trunk/rustbyexample/chapter15/example15_1$

完全没有泄漏!

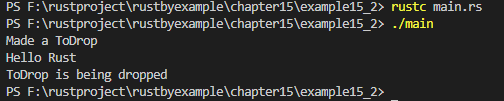

析构函数

Rust 中的析构函数概念是通过 Drop trait 提供的。当资源离开作用域,就调用析构函数。你无需为每种类型都实现 Drop trait,只要为那些需要自己的析构函数逻辑的类型实现就可以了。

运行下列例子,看看 Drop trait 是怎样工作的。当 main 函数中的变量离开作用域,自定义的析构函数就会被调用:

// 15.1节 析构函数

struct ToDrop;

impl Drop for ToDrop {

fn drop(&mut self) {

println!("ToDrop is being dropped");

}

}

fn main() {

let _x = ToDrop;

println!("Made a ToDrop");

println!("Hello Rust");

}

// rustc main.rs

// ./main编译运行:

PS F:\rustproject\rustbyexample\chapter15\example15_2> rustc main.rs

PS F:\rustproject\rustbyexample\chapter15\example15_2> ./main

Made a ToDrop

Hello Rust

ToDrop is being dropped

PS F:\rustproject\rustbyexample\chapter15\example15_2>

参见:

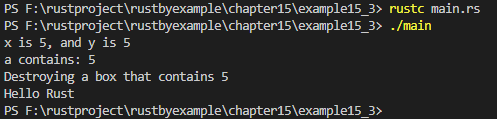

15.2 所有权和移动

因为变量要负责释放它们拥有的资源,所以资源只能拥有一个所有者 。这也防止了资源的重复释放。注意并非所有变量都拥有资源(例如引用)。

在进行赋值(let x = y)或通过值来传递函数参数(foo(x))的时候,资源的所有权 (ownership)会发生转移。按照 Rust 的说法,这被称为资源的移动(move)。

在移动资源之后,原来的所有者不能再被使用,这可避免悬挂指针(dangling pointer)的产生。

// 15.2节 所有权和移动

// 此函数取得堆分配的内存的所有权

fn destroy_box(c: Box<i32>) {

println!("Destroying a box that contains {}", c);

// `c` 被销毁且内存得到释放

}

fn main() {

// 栈分配的整型

let x = 5u32;

// 将 `x` *复制*到 `y`------不存在资源移动

let y = x;

// 两个值各自都可以使用

println!("x is {}, and y is {}", x, y);

// `a` 是一个指向堆分配的整数的指针

let a = Box::new(5i32);

println!("a contains: {}", a);

// *移动* `a` 到 `b`

let b = a;

// 把 `a` 的指针地址(而非数据)复制到 `b`。现在两者都指向

// 同一个堆分配的数据,但是现在是 `b` 拥有它。

// 报错!`a` 不能访问数据,因为它不再拥有那部分堆上的内存。

//println!("a contains: {}", a);

// 试一试 ^ 去掉此行注释

// 此函数从 `b` 中取得堆分配的内存的所有权

destroy_box(b);

// 此时堆内存已经被释放,这个操作会导致解引用已释放的内存,而这是编译器禁止的。

// 报错!和前面出错的原因一样。

//println!("b contains: {}", b);

// 试一试 ^ 去掉此行注释

println!("Hello Rust");

}

// rustc main.rs

// ./main编译运行:

PS F:\rustproject\rustbyexample\chapter15\example15_3> rustc main.rs

PS F:\rustproject\rustbyexample\chapter15\example15_3> ./main

x is 5, and y is 5

a contains: 5

Destroying a box that contains 5

Hello Rust

PS F:\rustproject\rustbyexample\chapter15\example15_3>

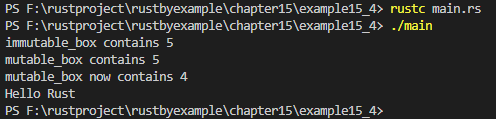

15.2.1 可变性

当所有权转移时,数据的可变性可能发生改变。

// 15.2.1节 可变性

fn main() {

let immutable_box = Box::new(5u32);

println!("immutable_box contains {}", immutable_box);

// 可变性错误

//*immutable_box = 4;

// *移动* box,改变所有权(和可变性)

let mut mutable_box = immutable_box;

println!("mutable_box contains {}", mutable_box);

// 修改 box 的内容

*mutable_box = 4;

println!("mutable_box now contains {}", mutable_box);

println!("Hello Rust");

}

// rustc main.rs

// ./main编译运行:

PS F:\rustproject\rustbyexample\chapter15\example15_4> rustc main.rs

PS F:\rustproject\rustbyexample\chapter15\example15_4> ./main

immutable_box contains 5

mutable_box contains 5

mutable_box now contains 4

Hello Rust

PS F:\rustproject\rustbyexample\chapter15\example15_4>

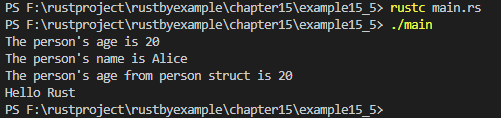

15.2.2 部分移动

在单个变量的解构内,可以同时使用 by-move 和 by-reference 模式绑定。这样做将导致变量的部分移动(partial move),这意味着变量的某些部分将被移动,而其他部分将保留。在这种情况下,后面不能整体使用父级变量,但是仍然可以使用只引用(而不移动)的部分。

// 15.2.2节 部分移动

fn main() {

#[derive(Debug)]

struct Person {

name: String,

age: u8,

}

let person = Person {

name: String::from("Alice"),

age: 20,

};

// `name` 从 person 中移走,但 `age` 只是引用

let Person {name, ref age} = person;

println!("The person's age is {}", age);

println!("The person's name is {}", name);

// 报错!部分移动值的借用:`person` 部分借用产生

//println!("The person struct is {:?}", person);

// `person` 不能使用,但 `person.age` 因为没有被移动而可以继续使用

println!("The person's age from person struct is {}", person.age);

println!("Hello Rust");

}

// rustc main.rs

// ./main编译运行:

PS F:\rustproject\rustbyexample\chapter15\example15_5> rustc main.rs

PS F:\rustproject\rustbyexample\chapter15\example15_5> ./main

The person's age is 20

The person's name is Alice

The person's age from person struct is 20

Hello Rust

PS F:\rustproject\rustbyexample\chapter15\example15_5>

参见:

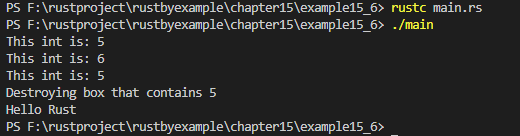

15.3 借用

多数情况下,我们更希望能访问数据,同时不取得其所有权。为实现这点,Rust 使用了借用 (borrowing)机制。对象可以通过引用(&T)来传递,从而取代通过值(T)来传递。

编译器(通过借用检查)静态地保证了引用总是 指向有效的对象。也就是说,当存在引用指向一个对象时,该对象不能被销毁。

// 15.3节 借用

// 此函数取得一个 box 的所有权并销毁它

fn eat_box_i32(boxed_i32: Box<i32>) {

println!("Destroying box that contains {}", boxed_i32);

}

// 此函数借用了一个 i32 类型

fn borrow_i32(borrowed_i32: &i32) {

println!("This int is: {}", borrowed_i32);

}

fn main() {

// 创建一个装箱的 i32 类型,以及一个存在栈中的 i32 类型。

let boxed_i32 = Box::new(5_i32);

let stacked_i32 = 6_i32;

// 借用了 box 的内容,但没有取得所有权,所以 box 的内容之后可以再次借用。

// 译注:请注意函数自身就是一个作用域,因此下面两个函数运行完成以后,

// 在函数中临时创建的引用也就不复存在了。

borrow_i32(&boxed_i32);

borrow_i32(&stacked_i32);

{

// 取得一个对 box 中数据的引用

let _ref_to_i32: &i32 = &boxed_i32;

// 报错!

// 当 `boxed_i32` 里面的值之后在作用域中被借用时,不能将其销毁。

//eat_box_i32(boxed_i32);

// 改正 ^ 注释掉此行

// 在 `_ref_to_i32` 里面的值被销毁后,尝试借用 `_ref_to_i32`

//(译注:如果此处不借用,则在上一行的代码中,eat_box_i32(boxed_i32)可以将 `boxed_i32` 销毁。)

borrow_i32(_ref_to_i32);

// `_ref_to_i32` 离开作用域且不再被借用。

}

// `boxed_i32` 现在可以将所有权交给 `eat_i32` 并被销毁。

//(译注:能够销毁是因为已经不存在对 `boxed_i32` 的引用)

eat_box_i32(boxed_i32);

println!("Hello Rust");

}

// rustc main.rs

// ./main编译运行:

PS F:\rustproject\rustbyexample\chapter15\example15_6> rustc main.rs

PS F:\rustproject\rustbyexample\chapter15\example15_6> ./main

This int is: 5

This int is: 6

This int is: 5

Destroying box that contains 5

Hello Rust

PS F:\rustproject\rustbyexample\chapter15\example15_6>

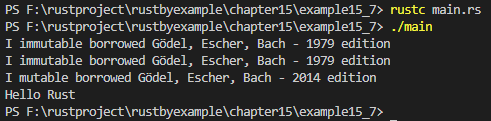

15.3.1 可变性

可变数据可以使用 &mut T 进行可变借用。这叫做可变引用 (mutable reference),它使借用者可以读/写数据。相反,&T 通过不可变引用(immutable reference)来借用数据,借用者可以读数据而不能更改数据:

// 15.3.1节 可变性

#[allow(dead_code)]

#[derive(Clone, Copy)]

struct Book {

// `&'static str` 是一个对分配在只读内存区的字符串的引用

author: &'static str,

title: &'static str,

year: u32,

}

// 此函数接受一个对 Book 类型的引用

fn borrow_book(book: &Book) {

println!("I immutable borrowed {} - {} edition", book.title, book.year);

}

// 此函数接受一个对可变的 Book 类型的引用,它把年份 `year` 改为 2014 年

fn new_edition(book: &mut Book) {

book.year = 2014;

println!("I mutable borrowed {} - {} edition", book.title, book.year);

}

fn main() {

// 创建一个名为 `immutabook` 的不可变的 Book 实例

let immutabook = Book {

// 字符串字面量拥有 `&'static str` 类型

author: "Douglas Hofstadter",

title: "Gödel, Escher, Bach",

year: 1979,

};

// 创建一个 `immutabook` 的可变拷贝,命名为 `mutabook`

let mut mutabook = immutabook;

// 不可变地借用一个不可变对象

borrow_book(&immutabook);

// 不可变地借用一个可变对象

borrow_book(&mutabook);

// 可变地借用一个可变对象

new_edition(&mut mutabook);

// 报错!不能可变地借用一个不可变对象

//new_edition(&mut immutabook);

// 改正 ^ 注释掉此行

println!("Hello Rust");

}

// rustc main.rs

// ./main编译运行:

PS F:\rustproject\rustbyexample\chapter15\example15_7> rustc main.rs

PS F:\rustproject\rustbyexample\chapter15\example15_7> ./main

I immutable borrowed Gödel, Escher, Bach - 1979 edition

I immutable borrowed Gödel, Escher, Bach - 1979 edition

I mutable borrowed Gödel, Escher, Bach - 2014 edition

Hello Rust

PS F:\rustproject\rustbyexample\chapter15\example15_7>

参见:

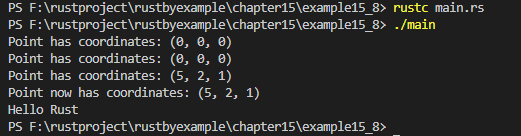

15.3.2 别名使用

数据可以多次不可变借用,但是在不可变借用的同时,原始数据不能使用可变借用。或者说,同一时间内只允许一次 可变借用。仅当最后一次使用可变引用之后,原始数据才可以再次借用。

// 15.3.2节 别名使用

struct Point { x: i32, y: i32, z: i32}

fn main() {

let mut point = Point {x: 0, y: 0, z: 0};

let borrowed_point = &point;

let another_borrow = &point;

// 数据可以通过引用或原始类型来访问

println!("Point has coordinates: ({}, {}, {})",

borrowed_point.x, another_borrow.y, point.z);

// 报错!`point` 不能以可变方式借用,因为当前还有不可变借用。

// let mutable_borrow = &mut point;

// TODO ^ 试一试去掉此行注释

// 被借用的值在这里被重新使用

println!("Point has coordinates: ({}, {}, {})",

borrowed_point.x, another_borrow.y, point.z);

// 不可变的引用不再用于其余的代码,因此可以使用可变的引用重新借用。

let mutable_borrow = &mut point;

// 通过可变引用来修改数据

mutable_borrow.x = 5;

mutable_borrow.y = 2;

mutable_borrow.z = 1;

// 报错!不能再以不可变方式来借用 `point`,因为它当前已经被可变借用。

// let y = &point.y;

// TODO ^ 试一试去掉此行注释

// 报错!无法打印,因为 `println!` 用到了一个不可变引用。

// println!("Point Z coordinate is {}", point.z);

// TODO ^ 试一试去掉此行注释

// 正常运行!可变引用能够以不可变类型传入 `println!`

println!("Point has coordinates: ({}, {}, {})",

mutable_borrow.x, mutable_borrow.y, mutable_borrow.z);

// 可变引用不再用于其余的代码,因此可以重新借用

let new_borrowed_point = &point;

println!("Point now has coordinates: ({}, {}, {})",

new_borrowed_point.x, new_borrowed_point.y, new_borrowed_point.z);

println!("Hello Rust");

}

// rustc main.rs

// ./main编译运行:

PS F:\rustproject\rustbyexample\chapter15\example15_8> rustc main.rs

PS F:\rustproject\rustbyexample\chapter15\example15_8> ./main

Point has coordinates: (0, 0, 0)

Point has coordinates: (0, 0, 0)

Point has coordinates: (5, 2, 1)

Point now has coordinates: (5, 2, 1)

Hello Rust

PS F:\rustproject\rustbyexample\chapter15\example15_8>

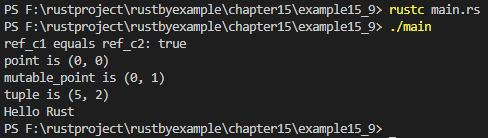

15.3.3 ref模式

在通过 let 绑定来进行模式匹配或解构时,ref 关键字可用来创建结构体/元组的字段的引用。下面的例子展示了几个实例,可看到 ref 的作用:

// 15.3.3节 ref模式

#[derive(Clone, Copy)]

struct Point{x: i32, y: i32}

fn main() {

let c = 'Q';

// 赋值语句中左边的 `ref` 关键字等价于右边的 `&` 符号。

let ref ref_c1 = c;

let ref_c2 = &c;

println!("ref_c1 equals ref_c2: {}", *ref_c1 == *ref_c2);

let point = Point{x: 0, y: 0};

// 在解构一个结构体时 `ref` 同样有效。

let _copy_of_x = {

// `ref_to_x` 是一个指向 `point` 的 `x` 字段的引用。

let Point {x: ref ref_to_x, y: _} = point;

// 返回一个 `point` 的 `x` 字段的拷贝。

*ref_to_x

};

// `point` 的可变拷贝

let mut mutable_point = point;

{

// `ref` 可以与 `mut` 结合以创建可变引用。

let Point {x: _, y: ref mut mut_ref_to_y} = mutable_point;

// 通过可变引用来改变 `mutable_point` 的字段 `y`。

*mut_ref_to_y = 1;

}

println!("point is ({}, {})", point.x, point.y);

println!("mutable_point is ({}, {})", mutable_point.x, mutable_point.y);

// 包含一个指针的可变元组

let mut mutable_tuple = (Box::new(5u32), 3u32);

{

// 解构 `mutable_tuple` 来改变 `last` 的值。

let (_, ref mut last) = mutable_tuple;

*last = 2u32;

}

println!("tuple is {:?}", mutable_tuple);

println!("Hello Rust");

}

// rustc main.rs

// ./main编译运行:

PS F:\rustproject\rustbyexample\chapter15\example15_9> rustc main.rs

PS F:\rustproject\rustbyexample\chapter15\example15_9> ./main

ref_c1 equals ref_c2: true

point is (0, 0)

mutable_point is (0, 1)

tuple is (5, 2)

Hello Rust

PS F:\rustproject\rustbyexample\chapter15\example15_9>

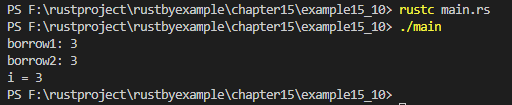

15.4 生命周期

生命周期(lifetime)是这样一种概念,编译器(中的借用检查器)用它来保证所有的借用都是有效的。确切地说,一个变量的生命周期在它创建的时候开始,在它销毁的时候结束。虽然生命周期和作用域经常被一起提到,但它们并不相同。

例如考虑这种情况,我们通过 & 来借用一个变量。该借用拥有一个生命周期,此生命周期由它声明的位置决定。于是,只要该借用在出借者(lender)被销毁前结束,借用就是有效的。然而,借用的作用域则是由使用引用的位置决定的。

在下面的例子和本章节剩下的内容里,我们将看到生命周期和作用域的联系与区别。

译注:如果代码中的生命周期示意图乱掉了,请把它复制到任何编辑器中,用等宽字体查看。为避免中文的显示问题,下面一些注释没有翻译。

// 15.4节 生命周期

// 下面使用连线来标注各个变量的创建和销毁,从而显示出生命周期。

// `i` 的生命周期最长,因为它的作用域完全覆盖了 `borrow1` 和

// `borrow2` 的。`borrow1` 和 `borrow2` 的周期没有关联,

// 因为它们各不相交。

fn main() {

let i = 3; // Lifetime for `i` starts. ────────────────┐

// │

{ // │

let borrow1 = &i; // `borrow1` lifetime starts. ──┐│

// ││

println!("borrow1: {}", borrow1); // ││

} // `borrow1 ends. ──────────────────────────────────┘│

// │

// │

{ // │

let borrow2 = &i; // `borrow2` lifetime starts. ──┐│

// ││

println!("borrow2: {}", borrow2); // ││

} // `borrow2` ends. ─────────────────────────────────┘│

println!("i = {}", i); // │

} // Lifetime ends. ─────────────────────────────────────┘

// rustc main.rs

// ./main编译运行:

PS F:\rustproject\rustbyexample\chapter15\example15_10> rustc main.rs

PS F:\rustproject\rustbyexample\chapter15\example15_10> ./main

borrow1: 3

borrow2: 3

i = 3

PS F:\rustproject\rustbyexample\chapter15\example15_10>

注意到这里没有用到名称或类型来标注生命周期,这限制了生命周期的用法,在后面我们将会看到生命周期更强大的功能。

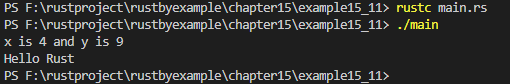

15.4.1 显示标注

借用检查器使用显式的生命周期标记来明确引用的有效时间应该持续多久。在生命周期没有省略1的情况下,Rust 需要显式标注来确定引用的生命周期应该是什么样的。可以用撇号显式地标出生命周期,语法如下:

foo<'a>

// `foo` 带有一个生命周期参数 `'a`和闭包类似,使用生命周期需要泛型。另外这个生命周期的语法也表明了 foo 的生命周期不能超出 'a 的周期。若要给类型显式地标注生命周期,其语法会像是 &'a T 这样,其中 'a 的作用刚刚已经介绍了。

foo<'a, 'b>

// `foo` 带有生命周期参数 `'a` 和 `'b`在上面这种情形中,foo 的生命周期不能超出 'a 和 'b 中任一个的周期。

看下面的例子,了解显式生命周期标注的运用:

// 15.4.1节 显示标注

// `print_refs` 接受两个 `i32` 的引用,它们有不同的生命周期 `'a` 和 `'b`。

// 这两个生命周期都必须至少要和 `print_refs` 函数一样长。

fn print_refs<'a, 'b>(x: &'a i32, y: &'b i32) {

println!("x is {} and y is {}", x, y);

}

// 不带参数的函数,不过有一个生命周期参数 `'a`。

fn failed_borrow<'a>() {

let _x = 12;

// 报错:`_x` 的生命周期不够长

//let y: &'a i32 = &_x;

// 在函数内部使用生命周期 `'a` 作为显式类型标注将导致失败,因为 `&_x` 的

// 生命周期比 `y` 的短。短生命周期不能强制转换成长生命周期。

}

fn main() {

// 创建变量,稍后用于借用。

let (four, nine) = (4, 9);

// 两个变量的借用(`&`)都传进函数。

print_refs(&four, &nine);

// 任何被借用的输入量都必须比借用者生存得更长。

// 也就是说,`four` 和 `nine` 的生命周期都必须比 `print_refs` 的长。

failed_borrow();

// `failed_borrow` 未包含引用,因此不要求 `'a` 长于函数的生命周期,

// 但 `'a` 寿命确实更长。因为该生命周期从未被约束,所以默认为 `'static`。

println!("Hello Rust");

}

// rustc main.rs

// ./main编译运行:

PS F:\rustproject\rustbyexample\chapter15\example15_11> rustc main.rs

PS F:\rustproject\rustbyexample\chapter15\example15_11> ./main

x is 4 and y is 9

Hello Rust

PS F:\rustproject\rustbyexample\chapter15\example15_11>

省略 隐式地标注了生命周期,所以情况不同。

参见:

15.4.2 函数

排除省略(elision)的情况,带上生命周期的函数签名有一些限制:

- 任何引用都必须拥有标注好的生命周期。

- 任何被返回的引用都必须 有和某个输入量相同的生命周期或是静态类型(

static)。

另外要注意,如果没有输入的函数返回引用,有时会导致返回的引用指向无效数据,这种情况下禁止它返回这样的引用。下面例子展示了一些合法的带有生命周期的函数:

// 15.4.2节 函数

// 一个拥有生命周期 `'a` 的输入引用,其中 `'a` 的存活时间

// 至少与函数的一样长。

fn print_one<'a>(x: &'a i32) {

println!("'print_one': x is {}", x);

}

// 可变引用同样也可能拥有生命周期。

fn add_one<'a>(x: &'a mut i32) {

*x += 1;

}

// 拥有不同生命周期的多个元素。对下面这种情形,两者即使拥有

// 相同的生命周期 `'a` 也没问题,但对一些更复杂的情形,可能

// 就需要不同的生命周期了。

fn print_multi<'a, 'b>(x: &'a i32, y: &'b i32) {

println!("'print_multi': x is {}, y is {}", x, y);

}

// 返回传递进来的引用也是可行的。

// 但必须返回正确的生命周期。

fn pass_x<'a, 'b>(x: &'a i32, _: &'b i32) -> &'a i32 {x}

//fn invalid_output<'a>() -> &'a String { &String::from("foo") }

// 上面代码是无效的:`'a` 存活的时间必须比函数的长。

// 这里的 `&String::from("foo")` 将会创建一个 `String` 类型,然后对它取引用。

// 数据在离开作用域时删掉,返回一个指向无效数据的引用。

fn main() {

let x = 7;

let y = 9;

print_one(&x);

print_multi(&x, &y);

let z = pass_x(&x, &y);

print_one(z);

let mut t = 3;

add_one(&mut t);

print_one(&t);

println!("Hello Rust");

}

// rustc main.rs

// ./main编译运行:

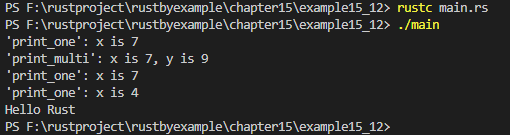

PS F:\rustproject\rustbyexample\chapter15\example15_12> rustc main.rs

PS F:\rustproject\rustbyexample\chapter15\example15_12> ./main

'print_one': x is 7

'print_multi': x is 7, y is 9

'print_one': x is 7

'print_one': x is 4

Hello Rust

PS F:\rustproject\rustbyexample\chapter15\example15_12>

参见:

15.4.3 方法

方法的标注和函数类似:

// 15.4.3节 方法

struct Owner(i32);

impl Owner {

// 标注生命周期,就像独立的函数一样。

fn add_one<'a>(&'a mut self) {self.0 += 1;}

fn print<'a>(&'a self) {

println!("'print': {}", self.0);

}

}

fn main() {

let mut owner = Owner(18);

owner.add_one();

owner.print();

println!("Hello Rust");

}

// rustc main.rs

// ./main编译运行:

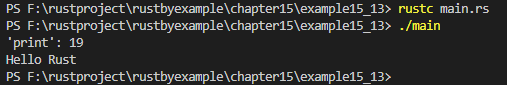

PS F:\rustproject\rustbyexample\chapter15\example15_13> rustc main.rs

PS F:\rustproject\rustbyexample\chapter15\example15_13> ./main

'print': 19

Hello Rust

PS F:\rustproject\rustbyexample\chapter15\example15_13>

译注:方法一般是不需要标明生命周期的,因为 self 的生命周期会赋给所有的输出生命周期参数,详见 TRPL。

参见:

15.4.4 结构体

在结构体中标注生命周期也和函数的类似:

// 15.4.4节 结构体

// 一个 `Borrowed` 类型,含有一个指向 `i32` 类型的引用。

// 该引用必须比 `Borrowed` 寿命更长。

#[derive(Debug)]

#[allow(unused)]

struct Borrowed<'a>(&'a i32);

// 和前面类似,这里的两个引用都必须比这个结构体长寿。

#[derive(Debug)]

#[allow(unused)]

struct NamedBorrowed<'a> {

x: &'a i32,

y: &'a i32,

}

// 一个枚举类型,其取值不是 `i32` 类型就是一个指向 `i32` 的引用。

#[derive(Debug)]

#[allow(unused)]

enum Either<'a> {

Num(i32),

Ref(&'a i32),

}

fn main() {

let x = 18;

let y = 15;

let single = Borrowed(&x);

let double = NamedBorrowed{x: &x, y: &y};

let reference = Either::Ref(&x);

let number = Either::Num(y);

println!("x is borrowed in {:?}", single);

println!("x and y are borrowed in {:?}", double);

println!("x is borrowed in {:?}", reference);

println!("y is *not* borrowed in {:?}", number);

println!("Hello Rust");

}

// rustc main.rs

// ./main编译运行:

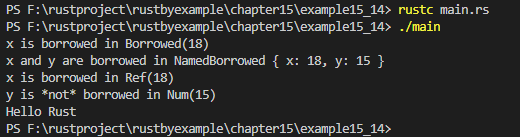

PS F:\rustproject\rustbyexample\chapter15\example15_14> rustc main.rs

PS F:\rustproject\rustbyexample\chapter15\example15_14> ./main

x is borrowed in Borrowed(18)

x and y are borrowed in NamedBorrowed { x: 18, y: 15 }

x is borrowed in Ref(18)

y is *not* borrowed in Num(15)

Hello Rust

PS F:\rustproject\rustbyexample\chapter15\example15_14>

参见:

15.4.5 trait

trait 方法中生命期的标注基本上与函数类似。注意,impl 也可能有生命周期的标注。

// 15.4.5节 trait

// 带有生命周期标注的结构体。

#[derive(Debug)]

#[allow(unused)]

struct Borrowed<'a> {

x: &'a i32,

}

// 给 impl 标注生命周期。

impl<'a> Default for Borrowed<'a> {

fn default() -> Self {

Self {

x: &10,

}

}

}

fn main() {

let b: Borrowed = Default::default();

println!("b is {:?}", b);

println!("Hello Rust");

}

// rustc main.rs

// ./main编译运行:

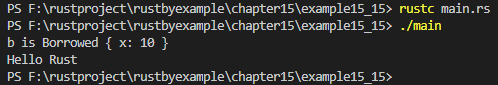

PS F:\rustproject\rustbyexample\chapter15\example15_15> rustc main.rs

PS F:\rustproject\rustbyexample\chapter15\example15_15> ./main

b is Borrowed { x: 10 }

Hello Rust

PS F:\rustproject\rustbyexample\chapter15\example15_15>

参见:

15.4.6 约束

就如泛型类型能够被约束一样,生命周期(它们本身就是泛型)也可以使用约束。: 字符的意义在这里稍微有些不同,不过 + 是相同的。注意下面的说明:

T: 'a:在T中的所有 引用都必须比生命周期'a活得更长。T: Trait + 'a:T类型必须实现Traittrait,并且在T中的所有 引用都必须比'a活得更长。

下面例子展示了上述语法的实际应用:

// 15.4.6节 约束

use std::fmt::Debug; // 用于约束的 trait。

#[derive(Debug)]

#[allow(dead_code)]

struct Ref<'a, T: 'a>(&'a T);

// `Ref` 包含一个指向泛型类型 `T` 的引用,其中 `T` 拥有一个未知的生命周期

// `'a`。`T` 拥有生命周期限制, `T` 中的任何*引用*都必须比 `'a` 活得更长。另外

// `Ref` 的生命周期也不能超出 `'a`。

// 一个泛型函数,使用 `Debug` trait 来打印内容。

fn print<T>(t: T) where

T: Debug {

println!("'print': t is {:?}", t);

}

// 这里接受一个指向 `T` 的引用,其中 `T` 实现了 `Debug` trait,并且在 `T` 中的

// 所有*引用*都必须比 `'a'` 存活时间更长。另外,`'a` 也要比函数活得更长。

fn print_ref<'a, T>(t: &'a T) where

T: Debug + 'a {

println!("'print_ref': t is {:?}", t);

}

fn main() {

let x = 7;

let ref_x = Ref(&x);

print_ref(&ref_x);

print(ref_x);

println!("Hello Rust");

}

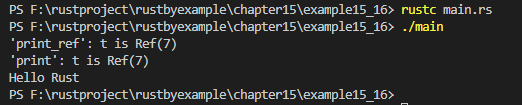

// rustc main.rs

// ./main编译运行:

PS F:\rustproject\rustbyexample\chapter15\example15_16> rustc main.rs

PS F:\rustproject\rustbyexample\chapter15\example15_16> ./main

'print_ref': t is Ref(7)

'print': t is Ref(7)

Hello Rust

PS F:\rustproject\rustbyexample\chapter15\example15_16>

参见:

15.4.7 强制转换

一个较长的生命周期可以强制转成一个较短的生命周期,使它在一个通常情况下不能工作的作用域内也能正常工作。强制转换可由编译器隐式地推导并执行,也可以通过声明不同的生命周期的形式实现。

// 15.4.7节 强制转换

// 在这里,Rust 推导了一个尽可能短的生命周期。

// 然后这两个引用都被强制转成这个生命周期。

fn multiply<'a>(first: &'a i32, second: &'a i32) -> i32 {

first * second

}

fn multiply2(first: &i32, second: &i32) -> i32 {

first * second * 2

}

// `<'a: 'b, 'b>` 读作生命周期 `'a` 至少和 `'b` 一样长。

// 在这里我们我们接受了一个 `&'a i32` 类型并返回一个 `&'b i32` 类型,这是

// 强制转换得到的结果。

fn choose_first<'a: 'b, 'b>(first: &'a i32, _: &'b i32) -> &'b i32 {

first

}

fn main() {

let first = 2; // 较长的生命周期

{

let second = 3; //较短的生命周期

println!("The product is {}", multiply(&first, &second));

println!("{} is the first", choose_first(&first, &second));

println!("The product2 is {}", multiply2(&first, &second));

}

println!("Hello Rust");

}

// rustc main.rs

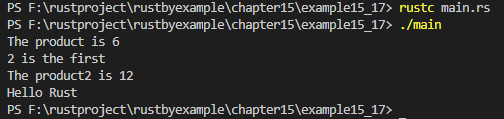

// ./main编译运行:

PS F:\rustproject\rustbyexample\chapter15\example15_17> rustc main.rs

PS F:\rustproject\rustbyexample\chapter15\example15_17> ./main

The product is 6

2 is the first

The product2 is 12

Hello Rust

PS F:\rustproject\rustbyexample\chapter15\example15_17>

15.4.8 static

'static 生命周期是可能的生命周期中最长的,它会在整个程序运行的时期中存在。'static 生命周期也可被强制转换成一个更短的生命周期。有两种方式使变量拥有 'static 生命周期,它们都把数据保存在可执行文件的只读内存区:

- 使用

static声明来产生常量(constant)。 - 产生一个拥有

&'static str类型的string字面量。

看下面的例子,了解列举到的各个方法:

// 15.4.8节 static

// 产生一个拥有 `'static` 生命周期的常量。

static NUM: i32 = 18;

// 返回一个指向 `NUM` 的引用,该引用不取 `NUM` 的 `'static` 生命周期,

// 而是被强制转换成和输入参数的一样。

fn coerce_static<'a>(_: &'a i32) -> &'a i32 {

&NUM

}

fn main() {

{

// 产生一个 `string` 字面量并打印它:

let static_string = "I'm in read-only memory";

println!("static_string: {}", static_string);

// 当 `static_string` 离开作用域时,该引用不能再使用,不过

// 数据仍然存在于二进制文件里面。

}

{

// 产生一个整型给 `coerce_static` 使用:

let lifetime_num = 9;

// 将对 `NUM` 的引用强制转换成 `lifetime_num` 的生命周期:

let coerced_static = coerce_static(&lifetime_num);

println!("coerced_static: {}", coerced_static);

}

println!("NUM: {} stays accessible!", NUM);

println!("Hello Rust");

}

// rustc main.rs

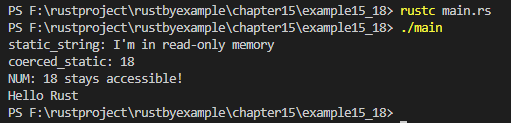

// ./main编译运行:

PS F:\rustproject\rustbyexample\chapter15\example15_18> rustc main.rs

PS F:\rustproject\rustbyexample\chapter15\example15_18> ./main

static_string: I'm in read-only memory

coerced_static: 18

NUM: 18 stays accessible!

Hello Rust

PS F:\rustproject\rustbyexample\chapter15\example15_18>

参见:

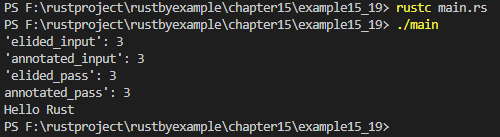

15.4.9 省略

有些生命周期的模式太常用了,所以借用检查器将会隐式地添加它们以减少程序输入量和增强可读性。这种隐式添加生命周期的过程称为省略(elision)。在 Rust 使用省略仅仅是因为这些模式太普遍了。

下面代码展示了一些省略的例子。对于省略的详细描述,可以参考官方文档的生命周期省略。

// 15.4.9节 省略

// `elided_input` 和 `annotated_input` 事实上拥有相同的签名,

// `elided_input` 的生命周期会被编译器自动添加:

fn elided_input(x: &i32) {

println!("'elided_input': {}", x)

}

fn annotated_input<'a>(x: &'a i32) {

println!("'annotated_input': {}", x)

}

// 类似地,`elided_pass` 和 `annotated_pass` 也拥有相同的签名,

// 生命周期会被隐式地添加进 `elided_pass`:

fn elided_pass(x: &i32) -> &i32{x}

fn annotated_pass<'a>(x: &'a i32) -> &'a i32{x}

fn main() {

let x = 3;

elided_input(&x);

annotated_input(&x);

println!("'elided_pass': {}", elided_pass(&x));

println!("annotated_pass': {}", annotated_pass(&x));

println!("Hello Rust");

}

// rustc main.rs

// ./main编译运行:

PS F:\rustproject\rustbyexample\chapter15\example15_19> rustc main.rs

PS F:\rustproject\rustbyexample\chapter15\example15_19> ./main

'elided_input': 3

'annotated_input': 3

'elided_pass': 3

annotated_pass': 3

Hello Rust

PS F:\rustproject\rustbyexample\chapter15\example15_19>