Financial Markets

本文是学习 https://www.coursera.org/learn/financial-markets-global这门课的学习笔记

这门课的老师是耶鲁大学的Robert Shiller https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_J._Shiller

Robert James Shiller (born March 29, 1946)[4] is an American economist, academic, and author. As of 2022,[5] he served as a Sterling Professor of Economics at Yale University and is a fellow at the Yale School of Management's International Center for Finance.[6] Shiller has been a research associate of the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) since 1980, was vice president of the American Economic Association in 2005, its president-elect for 2016, and president of the Eastern Economic Association for 2006--2007.[7] He is also the co‑founder and chief economist of the investment management firm MacroMarkets LLC.

Week 3

Stocks, bonds, dividends, shares, market caps; what are these? Who needs them? Why? Module 3 explores these concepts, along with corporation basics and some basic financial markets history.

Learning Objectives

- Describe the implications and institutions associated with the short term interest rate, and describe how to compute single and compound interest.

- Identify the difference between coupon and discount bonds, and calculate the present discounted value of discount bonds.

- Determine the origin, the meaning and the valuation of two debt securities: consols and annuities.

- Understand the meaning of forward rates and to describe how to calculate them

- Define the meaning and how to calculate the market capitalization of a company.

- Explain the structure of corporations in the U.S. and the implications of owning shares in a company.

- Identify the differences between common and preferred stocks, and the concepts of dilution and dividends.

- Describe how and why companies repurchase their shares.

- Describe the basics of corporate governance.

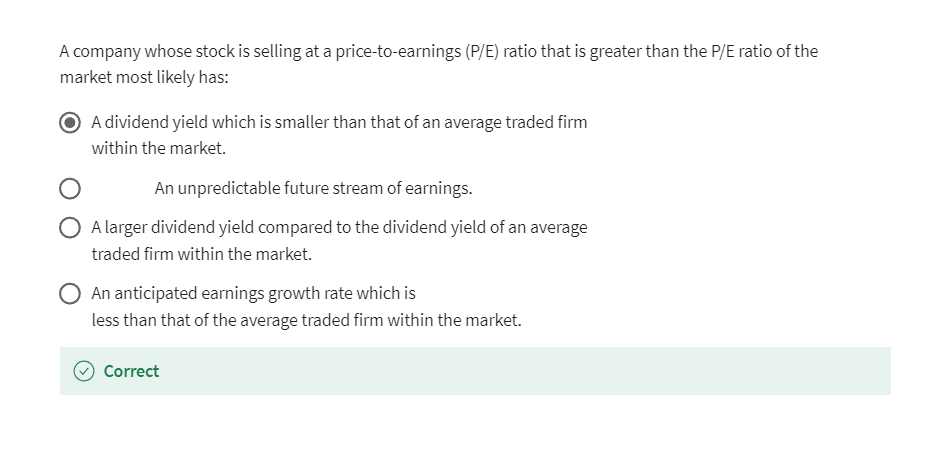

- Further understand the pricing of stocks and the price-to-earnings ratio.

文章目录

- [Financial Markets](#Financial Markets)

- [Week 3](#Week 3)

-

-

- [Learning Objectives](#Learning Objectives)

-

- Lesson #8

-

- [1982 Savings Account](#1982 Savings Account)

- [Federal Funds and Interest Rates](#Federal Funds and Interest Rates)

- [Compound Interest](#Compound Interest)

- [Discount Bonds](#Discount Bonds)

- [Consol and Annuity](#Consol and Annuity)

- [Forward Rates and Expectation Theory](#Forward Rates and Expectation Theory)

- Inflation

- Leverage

- [Lesson #8 Quiz](#8 Quiz)

- Lesson #9

-

- [Market Capitalization by Country](#Market Capitalization by Country)

- [The Corporation](#The Corporation)

- [Shares and Dividends](#Shares and Dividends)

- [Common vs. Preferred](#Common vs. Preferred)

- [Corporate Charter](#Corporate Charter)

- [Corporations Raise Money](#Corporations Raise Money)

- Dilution

- [Share Repurchase](#Share Repurchase)

- [PDV of Expected Dividends](#PDV of Expected Dividends)

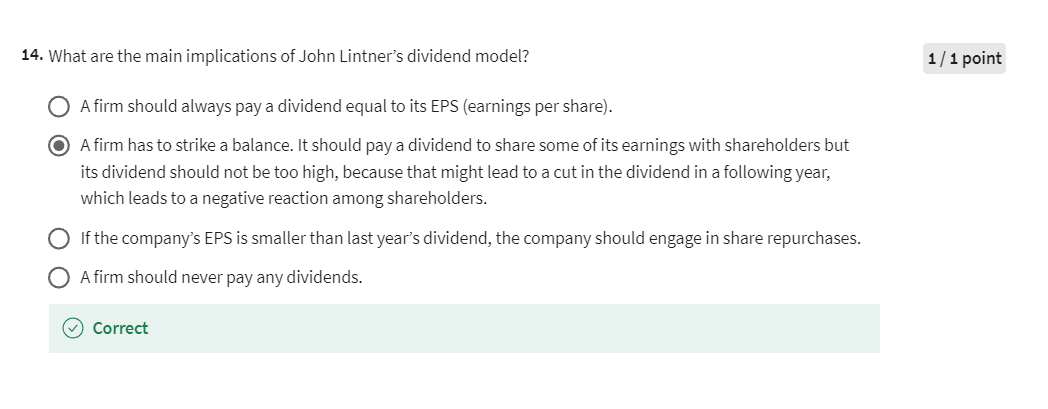

- [Why do firms pay dividends?](#Why do firms pay dividends?)

- [Lesson #9 Quiz](#9 Quiz)

- [Module 3 Honors Quiz](#Module 3 Honors Quiz)

- 后记

in the aftermath of: 在xxx之后

the situation in the aftermath of the financial crisis of 2008:2008年金融危机后的形势

passbook :存折

deposit:存钱

withdraw:取钱

you would present your passbook. And you could either deposit or withdraw. And they would enter your new balance in your passbook. 你应该出示你的存折。你可以存钱或取钱。他们会把你的新余额记入你的存折。

Compound Interest: 复利

coupon: 票息

maturity: 到期日

maturity of the bond:债券到期日

at par: 平价;按面值;根据票面价格

the coupon bonds which are more common, tend to be sold at par. 更常见的息票债券倾向于按面值出售。

Creditors:美 [k'redɪtəz] 债权人;债主;贷方;放款人;

impetus:美 [ˈɪmpɪtəs] 动力;原动力;推动;

board of directors: 董事会;理事会;

perpetuate:美 [pərˈpetʃueɪt] 延续;使永久化;使不朽;保持;

at discretion: 酌定;自行;随意

dividend is at discretion of firm,股息由公司决定

retained earnings:留存收益;保留盈利;未分配利润

expenditure:美 [ɪkˈspendɪtʃər] 花费;支出;开支;经费

capital expenditures: 资本支出

shares outstanding: 流通在外股票;净发股票

repurchase shares outstanding: 回购已发行股份

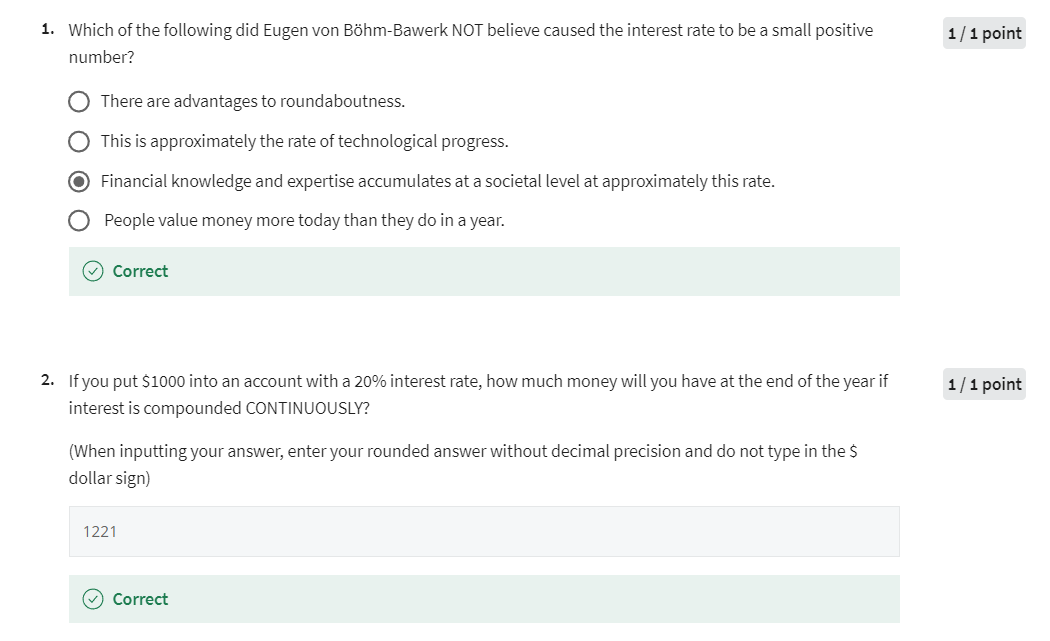

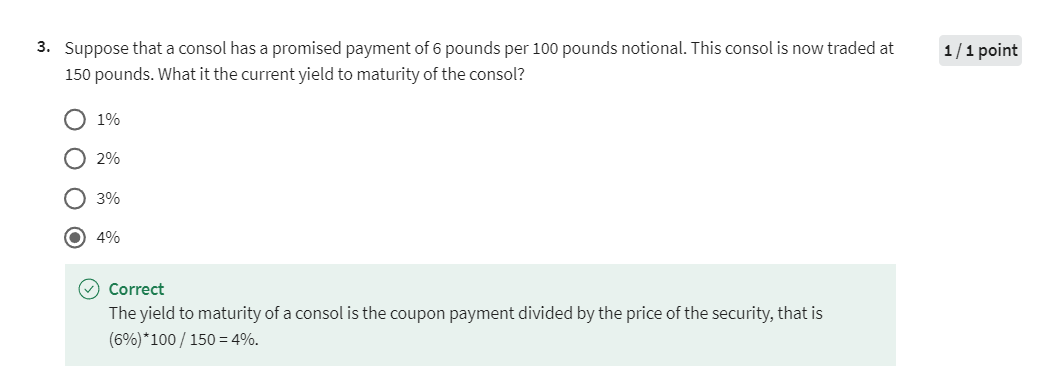

Lesson #8

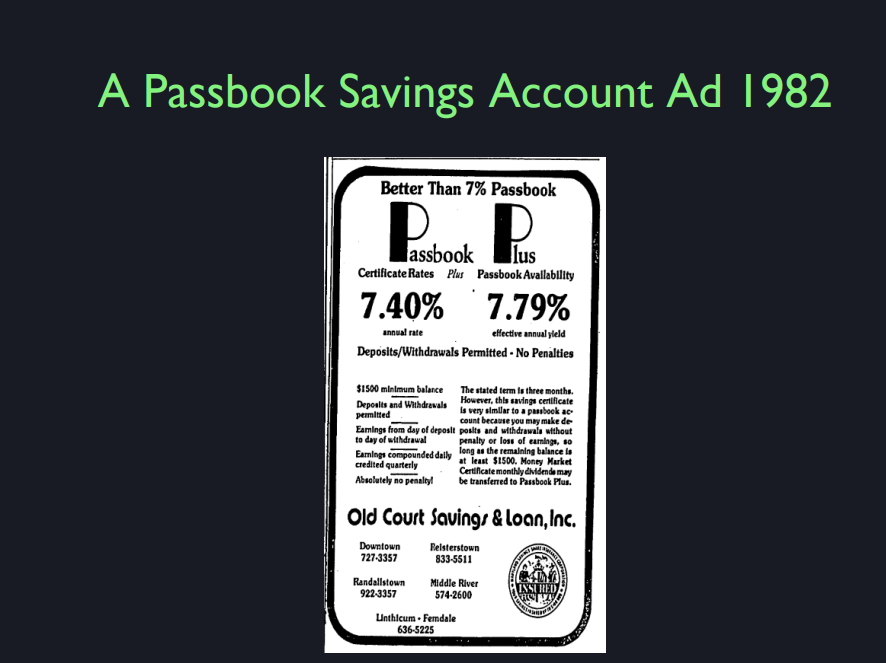

1982 Savings Account

I wanted to start though with just

a little bit about the current situation, or the situation in the aftermath of

the financial crisis of 2008, 2009. And that's not what I'm showing you, this ad here, I found it from 1982. What I'm commenting here is that

the current economic situation is rather different from 1982, and one sign of

that is you don't see these ads anymore. [LAUGH] I was just thinking,

where are the ads for savings accounts? They used to be all the time in

newspapers and magazines and TV. So I couldn't remember what they

looked like, so I looked it up. I found this ad, and

this is one you'd love to see today, but you won't see it today. [LAUGH] So

this is offering a passbook plus account with a 7.4 per

annum interest rate.

Now say, do you even know what

a passbook savings account is? Actually, I have my passport here,

I think. No, I don't, it's in my other,

LAUGH\] it looks like a passport. You used to walk into banks, everything has changed so much. You used to walk in, and there would be a teller. And you would present your passbook. And you could either deposit or withdraw. And they would enter your new balance in your passbook. It's like a statement. Whenever you need money, you go right to the bank and you pull it out. Meanwhile, you're earning 7.4% interest per year interest on it. So this actually is an ad for somebody's passbook plus savings account, which has a term, it says this in the fine print. Stated term is three months. That means you technically, they might make you wait three months to get your money out. However, this is very similar to a passbook account because you make deposits and withdrawals without penalty or loss of earnings. In this case, though, you have to keep your remaining balance at least $1,500. So here you are. You can go in and out of this account whenever you like. So it's basically an overnight account, you can take it out any day, any hour. It pays a nice interest rate, and it's insured by the government, so there's absolutely no risk. So this is what you want, right? But you're not going to get it \[LAUGH

because it doesn't exist anymore. Now the secret is if you

want something like this, you're going to have to pay

a negative interest rate. Because it just doesn't pay. This business just doesn't

pay because interest rates at the short end have gotten very low. And I'm going to come back to this. We're talking about the term structure. The term of any contract is the time that

you have to keep your money in it and can't get it out. So this one is technically

a three month term. But they're saying, trust us,

you can get it out any time. So it's basically overnight, absolutely

no penalty for withdrawing, it says. So we are in a situation in which at the short term,

interest rates are virtually 0. It's a historic event. And so, when we talk about interest rates, we might wonder why these

things are happening.

Federal Funds and Interest Rates

So this is the federal funds rate. Now, I'm mentioning term. Term is the time that you have to leave your money in and cannot get it out at least without a penalty. So this is the shortest term interest rate in the United States. It's called the Federal Funds Rate, and it's an overnight rate. Now, most of the people who deal in this maturity of one day are banks, because individuals normally don't borrow money overnight. It's too short an interval. Only people who are very sharp pencils and very professional will borrow money for one day. But it's a lively market, largely among bankers. So this is the interest rate on federal funds in the United States from 1954 to the present. So the ad that I showed you was from somewhere around here. I picked the high interest rate time looking for an ad. Those were different times. Look where we are now. This is amazing. It's right at zero. And it's been at zero ever since the crisis. Now, it's going to pick up. In fact, it's already picking up. Do you see this little uptick at the end? That was the decision of the government, the US Federal, well, The Federal Reserve under Janet Yellen to raise interest rates, and it got a lot of attention.

I have to say, I'm not very impressed by this raise of interest rates because it's virtually zero still. So something funny is going on here, wouldn't you say? If you looked at this whole, if your job was to predict interest rates and you were standing here in say 2004, would you have predicted this? Well, absolutely no. I shouldn't, say, there might have been someone who predicted this. But as far as I know, no one saw this coming but something very strange is happening. It'd be nice to understand this interest rate market. Now you might first of all say that well this is a targeted interest rate. The Federal Reserve announces a Federal Funds rate target, and they do everything they can and they've decided to put it at virtually zero. So you have to understand the Fed, but maybe you don't have to understand Janet Yellen or Ben Bernanke because these are the chairs of the of the Federal Reserve. Because anyone would do the same thing. It's an economic crisis that's brought equilibrium, short term interest rates down to zero. And to give you an idea that it is an economic crisis and it's not the personality of Janet Yellen that is accounts for this behavior.

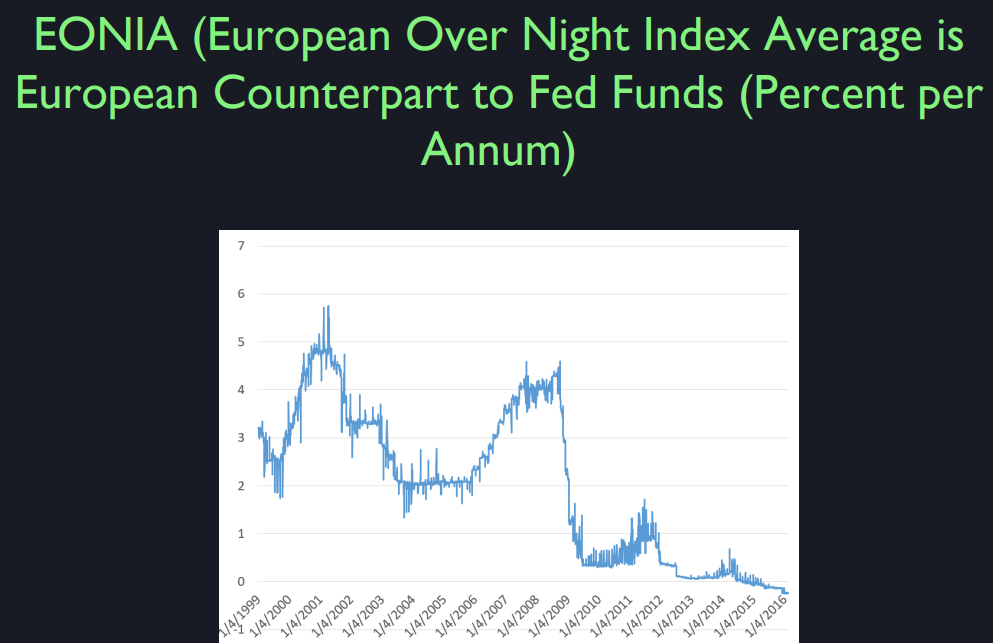

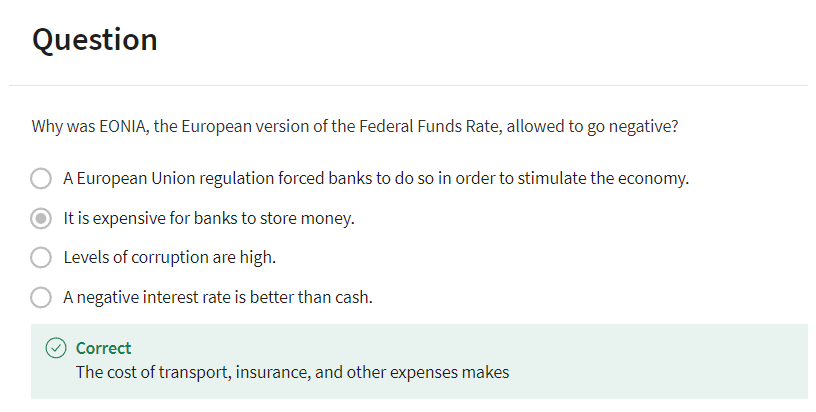

Let's look at Europe. So this is the European counterpart to the federal funds rate. It's called EONIA, European Overnight Index Average. So it's the same thing. Banks in Europe lend to each other overnight, and this is the interest rate. Now this only goes, I got these data from the European Central Bank and so that's why it only goes back to 1999. But you can see that it has the same downward path since 2000. Now, it's even more interesting because in the US, it stopped at zero. But it somehow knows no zero bound. In fact it's been negative for over a year. And it just seems to be trending down. Is this gonna... What is it... Now, if I asked you to forecast where it will be in 10 years, where will EONIA be in 10 years? Well, you might be inclined to forecast oh, I don't know -3%. Anyone believe that? Anyone offer a forecast? What do you think it will be? It can't go too far negative because the banks have the option of just holding on to cash. Why should we lend money at a negative interest rate? Well, that's an interesting question. You can blame Mario Draghi who's head of the European Central Bank, who he and the others at the bank have lowered the interest rate that they offer to European banks on deposits at the European Central Bank to a negative number.

So that you could say it was the decision of the Central Bank. But still it seems odd. Why does a bank ever invest money at a negative rate when they can just pull the money out and hold cash? Cash by definition, I mean real cash, paper money. Those those Euro notes that you have in your pocket, they pay exactly zero interest. So why would a bank lend to another bank at negative? Does anyone have an idea? Why would they? They are doing it right. We know they're doing it. Why are they lending to another bank at a negative rate? It's costly to store cash. First of all, if it becomes known that you have large amounts of cash in your vault, thieves might come and steal it, so you have to buy insurance against that. And then the insurance company will impose costs on you. Plus you have to hire those trucks to drive it. You know, it's not set up... Banks don't hold huge amounts of cash in their vaults. So yeah, so you've got to hire trucks and armed guards and it sounds... I think also it's just irregular, we don't do this. We don't have you billions in our vault. We have to get a bigger vault maybe because they don't. What's the biggest Euro note? It's probably like a hundred, does anyone know? 500. That's it 500. In the United States, it's only $100. So to store a billion dollars, you need a big vault. So you have to buy a new vault. It's silly things like that that allow negative interest rates. I think that as they learn that it's going to be harder to have a negative. So right now it looks like in this latest data shown here it looks like about -30 basis points where 30, a basis point is one hundredth of a percentage point. So it's minus a third of a percent. So they can get it lower than that for a while anyway. But anyway, it's just trying to understand why did it get so low.

So this brings us to causes of interest rates. There was a famous book written by Eugen Bohm von Bawerk in 1884, Capital and Interest, which said, "Interest rates tend to be small positive numbers like 3% or 5% because of technical progress, time preferences and advantages to round aboutness." I think he said round, he wrote in German so how do you say round aboutness in German? It's not exactly an English word either. I'll let you think about that. It's probably a translation of some long German word. But he said, why is it, and where does this number 3% come from? Why is it 3 percent or 5%? Well, he said, "It's because the rate of progress is something like 3%." Also so that sounds plausible, right. The economy is moving forward. So money, one dollar today is really if you take into account what will happen to the economy, it's really like a dollar, $1.03 and in a year. The other thing is time preferences. He said, "People are just naturally impatient. It's built into our, I don't think he said built into our neural structure, but maybe he meant that. So we just want more today. So if a dollar and three cents in a year is equivalent to a dollar today because I wouldn't... I prefer it now. And so I'll take a cut in what I have to get it now rather than later. And finally, advantages to round aboutness. That is advantages to more delayed and complicated production process. So for example, I can talk to... I'll just give you a very homely example. I can talk to a apple orchard and say, "How many apples can you give me today?" And so the guy quotes so many bushels of apples. And then you come back and say, "That's not enough, I want more apples." And he'll say, "Hey, you know our trees only produce so much." But you say, "I want more.". And then he said, "Well, okay, what I'll do instead of giving you apples now, I will sell my apples, buy fertilizer and I get stronger and bigger trees next year and I'll have more for you. But you have, more round about." Right. "I'm converting apples into fertilizer and I'm making the trees bigger. I can get you more next year." That's a roundabout production process. And so there's an advantage to that. So all three of those were causes of interest.

Do you think that low interest rates are contributing to inequality? There's definitely some connection because a lot of elderly people retire on fixed incomes. And if they have a rule that they will only consume the interest and the interest is zero, they're in big trouble. And that is unfortunately the situation. It's unfortunate that our efforts at policy can't help everybody. So monetary policy is a very blunt tool. You may feel that you have to cut interest rates to help the economy move ahead, but it doesn't affect everyone the same. And any time it doesn't, that, it has a potential to raise inequality.

Compound Interest

Now I wanted to give you a lesson, which,

I somehow have the impression you learned in high school,

did you learn compound interest? It's supposed to be such a basic math

point but let me just reiterate it. Suppose there's an annual rate of interest

r, and suppose that you're putting your money in a savings account in a bank

that promises to compound once per year. What does that mean? That means that your interest is

applied to the account once a year and you start earning interest on your

interest at the end of the year. So if I put $100 into an account

paying 3% compounding once a year, and

I go to the bank after six month and I say I'd like to cash out of my account,

what's it worth? They would say $100.00 because we haven't

credited your annual interest yet. So then you go [LAUGH] if you wait a full

year you can come back to the bank and now you get $103, now your account

is marked up for compounding. If you go back to the bank in 18

months since you deposited it, and you ask for your money,

they'd say well now you have $103 [LAUGH] because we haven't credited your

new interest for this year. You have to wait two years and

after two years how much do you have? You have 1.03 times 1.03, is little over 1.06,

if you have annual compounding. Now the banks often compound

more often than once a year so suppose they compound twice per year. You put in $100 in a 3% compounding twice

per year, if you went to get your money in the first six months,

you would still just get 100 back. After six months, you'd get 101.50, if you went back after nine months,

you'd get $101.50. You'd have to wait two years, no,

one full year, did I say that right? Yeah, you'd have to wait a full year and then you would get 1.015

squared times $100. You see where we're going on this,

if it's compounded twice per year the balance is 1 plus r

over 2 times 2t after t years. Where t is any number,

which is either one or, one plus, it's either an integer or an integer plus a half,

in between it's a step function. And if it's compounded n-times a year, the balance is one plus r

over n to the nt-th period. Now if you take the limit of this

expression as n goes to infinity, you get what's called

continuous compounding, and then the balance is e to the rt,

where e is the natural number. So if they continuously compound, it improves your interest

payments a little bit more, unless r is really big it's not, or t is

really big, it's not a huge difference.

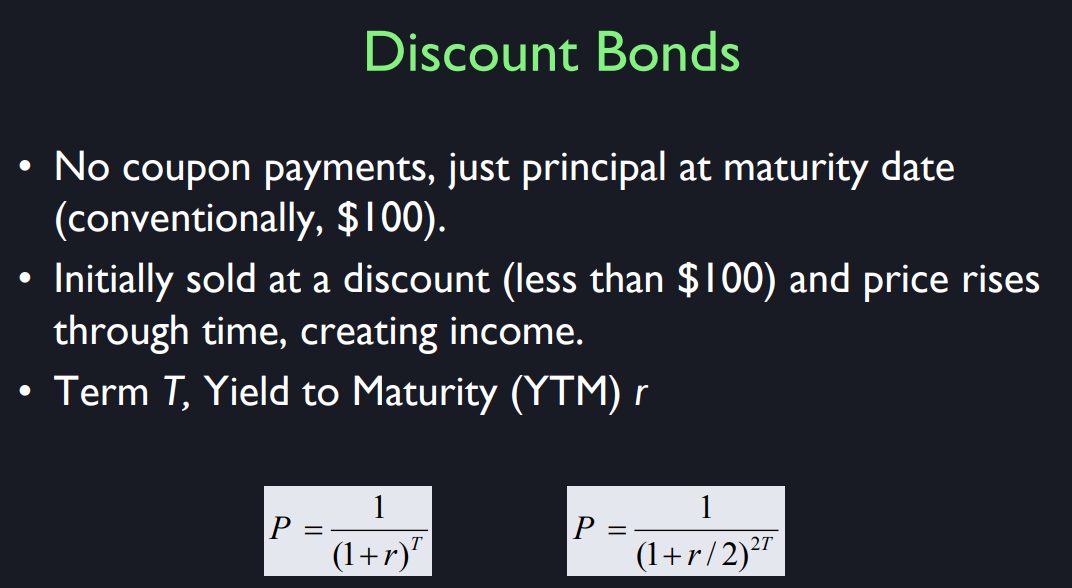

Discount Bonds

Now, I wanted to find a discount bond. Bonds typically pay coupons. This is an old word but they still say coupons. It used to be, that if you invested in a corporate bond or a government bond it would be on a piece of paper they would give you. This is like for hundreds of years. And around the exterior of the pieces of paper, were little coupons that you would clip every six months typically. And you would clip your coupons every six months and take them to a bank, and the bank would then give you the money. So, each coupon would be so much money.

And then, at the end of the maturity of the bond, you could take the whole thing back and you get your amount back. So a typical bond back then, in 1900, and 1800, and 1700. Going way back. If you bought a 100-dollar bond, and it was issued for 100, and had say as a three-dollar coupon. Then, you would pay 100. You'd wait six months, you'd clip a coupon, and it would say, pay to the bearer one dollar and fifty cents. You'd go to the bank and get your one dollar and fifty cents. And you can see some of these bonds, they're framed and on display. Ones that defaulted, otherwise, the coupons would be already clipped and gone. You can see them, I think they're on displays on the fourth floor of this building.

A discount bond is a bond that carries no coupon. Now, why would you buy a bond that carries no coupon? How do you get interest from it? This is also time in memorial. People have traded discount bonds for a long time, and the answer is, because you buy it for less than 100. You buy it at a discount. So, they tend to be two different kinds of bonds, the coupon bonds which are more common, tend to be sold at par. You buy it initially for 100, and you sell it for a 100, you get back at the end when it matures after so many predefined years. With a discount bond, there are no coupons but of course, you buy it at a discount. There would be no other reason to buy it. Maybe today they're selling not at a discount with a negative interest rates. But normally, they're sold at a discount. We still call them discount bonds even there's a negative interest rate than they're selling for more than $100 initially.

So, if we look at the price of the discount bond, we can infer the yield to maturity from that bond. So, if someone says, I have a bond that will pay let's say, one dollar in T years, and it's compounding once a year, and the price I want is P, I can compute using this formula. What the yield to maturity is. So, I would basically take one over P, if solving this equation, I take one over P to the one over T power, and that's the yield to maturity. In a sense paying an interest rate of r, every year. Compounding once a year if I call it that. But typically, bonds pay interest rate every six months, that's the tradition. So, you might use this formula instead which has the bond compounding twice a year. If T is a number of years to maturity, and P is the price, then we will take P as the present value of the principal which I have as one dollar here, divided by one plus or over two, to the two T. So, the price today of the bond is called, the present value.

If it's a one dollar principal of one dollar at time capital T. And as a general rule, P is going to be less than one. I say is a general rule because it might not hold right now which is a little puzzling. But over most of history, it's a discount. P is less than one. So, is that clear? Any questions about that? You have to specify the compounding interval. But normally, for pedagogical purposes, it's convenient to take the compounding as once a year. And we just use this formula. By the way, you could do it continuously till you could say, what does that continuously compounded yield to maturity. And that we have P equals e to the minus r times capital T.

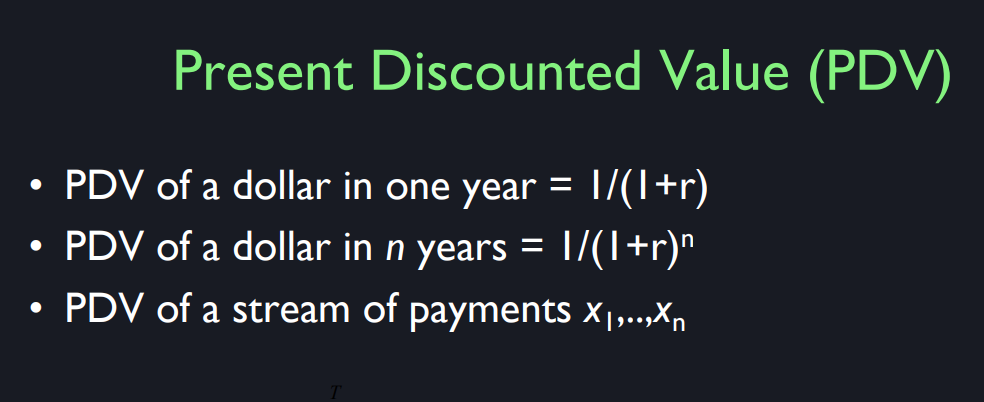

Okay. Now, we can define the present discounted value of any cash flow, not just a coupon flow which would be the case for a coupon bond, or the principal after T years for discount bond. Because we know that implicit in market prices for discount bonds, we can calculate the present discounted value of a dollar in any number of years. So, what is a dollar one year today? What is the present discounted value of that? It's one over one plus r, where r is the yield to maturity on a one year discount bond. And what is the present discounted value of a dollar in n years? It's one over one plus r to the nth power. Now, this is obvious to a banker who always thinks. When you talk money with a banker, and you're talking about money in future years, there's a little calculator going in his head, he has memorized the prices of all these discount bonds going out. And he's translating it into present value or present discounted value, PDV. Amateur's mess this up. Instead, they become vulnerable to fishes. Lots of people make mistakes. Maybe you should develop the habit of always computing the present discounted value. On the other hand, you live in a very good time for ignoring this. Because right now, interest rates are virtually zero. But it will come back. I think Nick you are right, we are going to have two percent and higher interest rates at some date in the future. I just don't know when. If you have a cash flow, x sub t, where x sub one is the money coming in in one year. x sub two is the money coming in in two years. And let's assume that the discount rate is the same for all these different maturity. This is a simplification. Then the present discounted value of the cash flow is the summation t equals one of the capital T, of the cash flow x sub t, divided by one plus r over the t. That's one of the most famous formulas in finance.

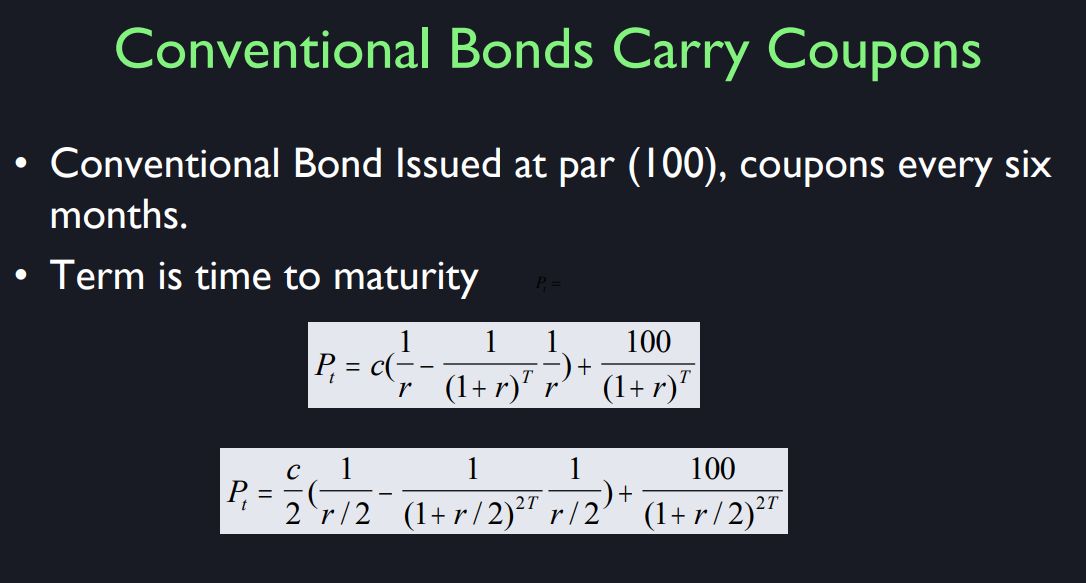

So, now let's look at a conventional coupon varying bond which is issued at par. How do they issue them at par by the way? It's tradition to issue at par because you're getting your interest in the form of coupons. What they have to do is judge the market. If I want to issue with par, what coupon is the market demanding on a 100? And once I know that, I'll just pick that coupon, and I can be pretty sure that my bond will be picked up for 100 because I've got the market coupon. So, I'm going to use c for the amount of coupon. Now, this is measured in currency, if we're dealing in dollars, c is so many dollars and the prices in so many dollars. And what it is now?

Now, here I have two versions. This is compounded annually, and this is the more realistic compound in every six months where t measures years. So, what you get in a simple case when you buy a coupon bond, is you get after one year, this is the annual compound after one year, I can clip a coupon for c dollars. And then, I have to wait another year, and then I can clip a coupon for c dollars again, and clip another coupon in three years for c dollars. And then at the end, I get my last coupon of c dollars, plus the principal which is a 100. So, I get 100 plus c dollars at the end. What is the present value of that if it's discounted at rate r? It turns out that's the formula for the present value. Now it's interesting to take the limit of this as t goes to infinity. If t goes to infinity, this term goes to zero, right? And this term goes to zero. So, we're left with c times one over r. So, that's the console. I think I have another slide for that. This is the more complicated formula for six-month compounding. This formula was sufficiently difficult that in the old days, and people didn't have calculators. Bankers would carry around the table, bond yield table. Also you can't solve this back. If I'm told the price of a bond, and I want to compute the yield to maturity r, I've got to solve this equation for r. And you can't. It's not algebraically possible. Unless, t is very small. So, you need a book. But now, it's probably already on your mobile phone. I think it is. I know it is. Go to Wolfram Alpha on your mobile phone and you'll get, or there must be other places. Must be hundreds of places that will solve this equation for you because it's standard. So many people think in terms of present values. And they want to know what the yield to maturity. What's the interest rate on a bond given its price.

Consol and Annuity

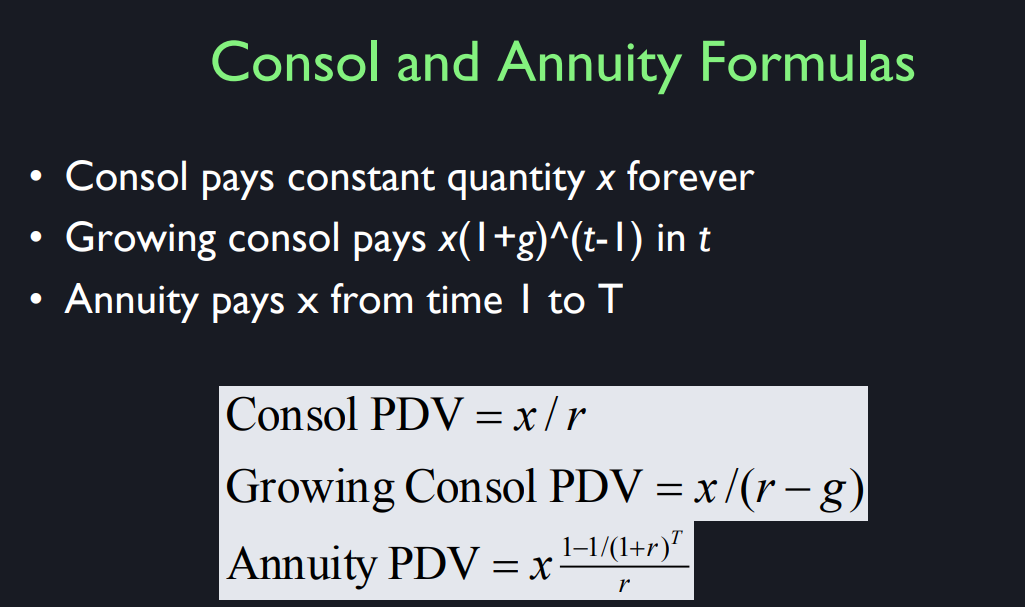

So I already mentioned a consol

is one that pays a quantity. What I was saying c or whatever x forever. And the consol present this kind of

value is x over or coupon over r. So it's kind of obvious in the case of a,

why do we call them consols by the way? Because in Britain,

in the 1700s, the government of the United Kingdom issued

bonds with no maturity date. They promised to pay this coupon forever,

and the only way they could get out

of it was by buying them back. And those bonds, well, there was

some adjustments made in the 1880s. They're still paying the coupon. The British government hasn't

defaulted in all that time. And so it's not forever,

but it's close to forever. I mean, several hundred years,

a long time to be paying a coupon.

在你提供的上下文中,"consol" 指的是由英国政府发行的一种没有到期日的政府债券。这些债券也被称为永久债券,最早在18世纪发行,并承诺无限期支付固定的利息。唯一能停止支付这些利息的方式是政府回购这些债券。

"consol" 是 "consolidated annuities" 的简称,反映了这些债券合并了早期的债务。consol 的主要特征包括:

- 永续性:它们无限期支付利息(或至少支付非常长的时间,如几百年)。

- 固定利息:利息支付是固定和定期的。

- 无到期日:与典型债券不同,consol 没有固定的还本日期。

consol 的现值可以用公式 ( \frac{x}{r} ) 计算,其中 ( x ) 是年利息支付,( r ) 是利率。这个公式反映了收到固定支付的永续价值由支付金额除以利率决定。

In the context you provided, a "consol" refers to a type of government bond issued by the United Kingdom that has no maturity date. These bonds, also known as perpetual bonds, were first issued in the 1700s and promise to pay a fixed coupon (interest payment) indefinitely. The only way the government can stop making these payments is by buying back the bonds.

The term "consol" is short for "consolidated annuities," reflecting the way these bonds consolidated earlier debt. The key characteristics of consols are:

- Perpetuity: They pay a coupon forever (or at least for a very long time, such as several hundred years).

- Fixed Coupon: The interest payments are fixed and regular.

- No Maturity Date: Unlike typical bonds, consols do not have a set date when the principal must be repaid.

The present value of a consol can be calculated using the formula ( \frac{x}{r} ), where ( x ) is the annual coupon payment and ( r ) is the interest rate. This formula reflects the idea that the value of receiving a fixed payment forever is determined by the payment amount divided by the interest rate.

Now it's simple to understand

the consol present that says the price of the consol

p is equal to c over r. You can just return that, turn it around. It says the yield to maturity

on a consol is c over p, and that's kind of obvious, right? If the consol is paying a 3 pound coupon,

and it's selling for 200 pounds,

I say what is the yield to maturity on it? Well it's 3 pounds divided by 200 pounds. In that case it would be, if it was

3% yield to maturity, I'm sorry if it was a 3% coupon issued,

it's now paying one and a half percent yield to maturity

because the price has gone up. This is an important point with bonds. The coupon is fixed at the time

the bond is issued but the market price of the bond

changes through time so if the British government

issued a 3 pound consol for 100 pounds and

that consol is selling for £200 today, the yield to maturity is

down to 1.5% instead of 3%. But this is no fault of the British

government, they are true to their word. They are paying the consol as promised,

it's the market that does it so bonds are risky, they have market risk

even if there is no default risk. If you buy a consol,

you know you won't live forever. The British government may

live forever but you won't, so you're going to want to sell

the coupon at some point. The British government does not

guarantee the rate that you will get, the price you will get for

selling your consol. So, there's market risk for

our consol and for any debt instrument,

long term debt instrument. By the way, if a bank or a company or a government were to issue

a usually companies don't issue consols because nobody

believes they'll last forever. Patriots in Britain might believe that

the British government will last forever. Although I can tell you it won't [LAUGH],

not forever. Nothing is forever. But they imagine it's forever, so

they're willing to buy British consols.

But what if the British government

did something even more dramatic? They say, we're going to have the coupon

on the Consol growing at a constant rate. So, it's going to start out at 3 pounds,

and then it's going to grow

at a rate g per year. G is a percent of growth per year forever. Well what is the present

value of an amount x if the rate is the yield to maturity or interest rate is r and

the x is going to grow at rate g? Well, it turns out the growing consol

present discounted value is x over r minus g. So, by the way, what happens if g is

greater than r [LAUGH] or g equals r? Any idea on that? Well, I think you probably

can figure this out. It's, if g equals r it's x divided by 0,

it's infinite. That's because it's the series that

you're summing is not convergent. If you're getting an amount that's

growing at the rate of interest, the present value is infinite and if it's growing at greater than the rate

of interest, well the formula breaks down. It's still infinite. So that's why we get puzzled

about the present situation. If the interest rate is 0 then

consols don't even converge. How can that be? Doesn't the interest rate always

have to be above the growth rate. How can anything,

nothing can have an infinite price. Well, I guess the answer is short

term interest rates have 0 but longer term interest rates

are still positive so and the US doesn't have consols, but we have something analogous to consols,

like land, for example. That lasts forever, as far as we know. You can rent it out or you can plant

crops on it, as far as we know, forever. Maybe those crop, what about land? Aren't crop values rising through time? So that g is a positive number? And if interest rates are,

they can't be 0, they have to be, bond rates have to be above

0 otherwise assets that have growing payments would be

worth an infinite amount.

Now this is an annuity

present discounted value. Now an annuity is like

a consol except that it stops after a certain number of years. In a typical annuity,

a typical annuity is a home mortgage. When you buy a house,

the typical financing you'll get, is that you will pay now

the compounding integral is monthly. They think it's not realistic

to ask ordinary people to pay their mortgage every six months

because it's too hard for them. They'd have to,

they wouldn't remember to save and they wouldn't have enough

money to pay after six months. So we gotta move to a monthly schedule for

individuals. A typical and that's not,

this is not compounding monthly. This is the present value

of X dollars every year, starting in one year and

then again in two years, then again in three years and

the last payment is T years. This is different from the present

value for a corporate bond, or for a coupon carrying bond because there's

no principle repayment at the end. I'm talking about,

I think I have another slide on mortgages. I'll come back to that. But I tell you realistically, these financial instruments are designed

around human imperfections. People find it difficult

to pay back a mortgage. And what they'll find

especially difficult, is to pay a balloon payment at the,

they call it a balloon payment. There used to be mortgages like this. You would borrow to buy your house, you

would say, I'm going back to the 1920s. The house cost $10,000,

typical house in the 1920s. You borrowed 9,000. You've got your own money to put up. The 9,000, then you pay back

the money at a rate interest. And then, but at the end, you don't owe

anything except the last monthly payment. So that's what an annuity is.

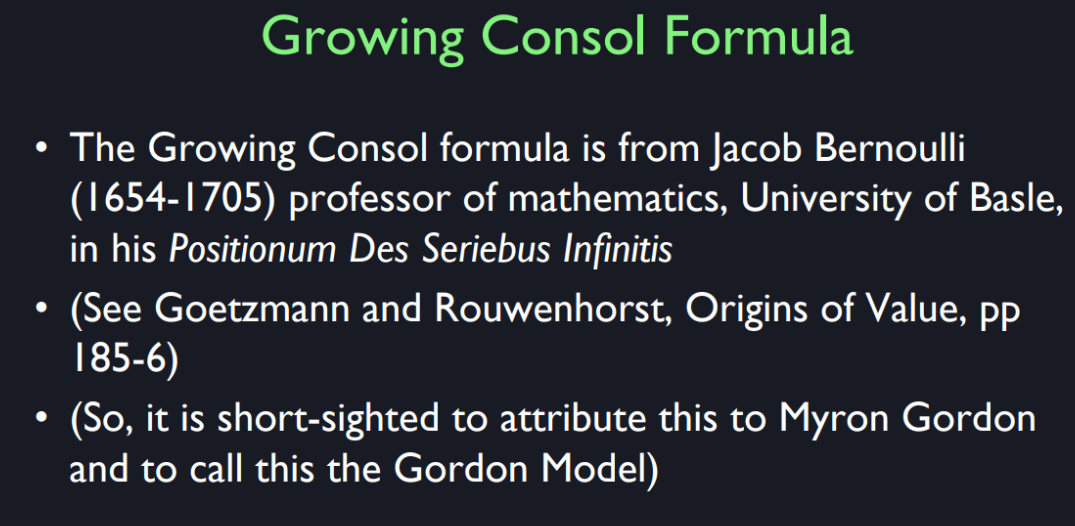

This is a little history of thought,

actually the Growing Consol Formula has been

called the Gordon Rule according to Myron Gordon who was a professor of

economics about a half century ago. But actually it goes

back to Jacob Bernoulli, I learned that from Will Goetzmann and

his co author Geert Rouwenhorst here. So it's an old formula

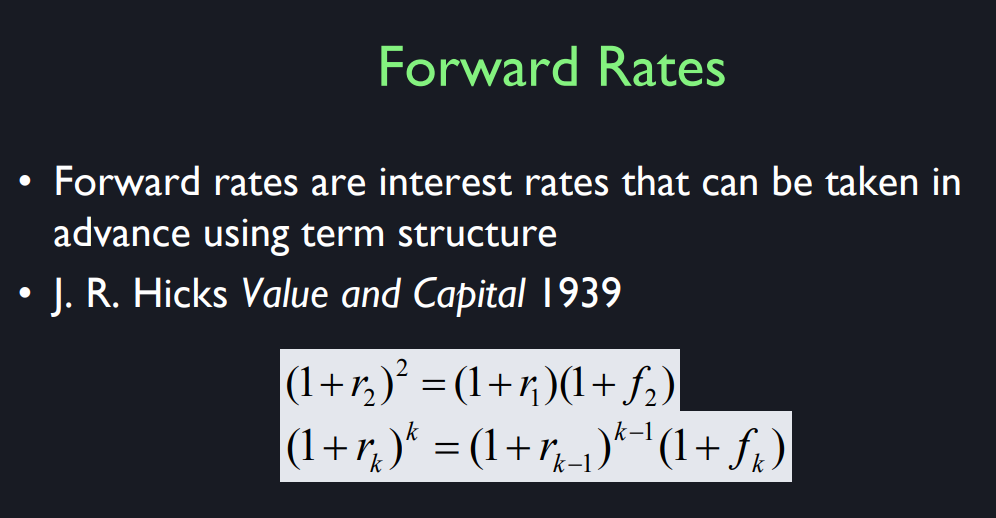

Forward Rates and Expectation Theory

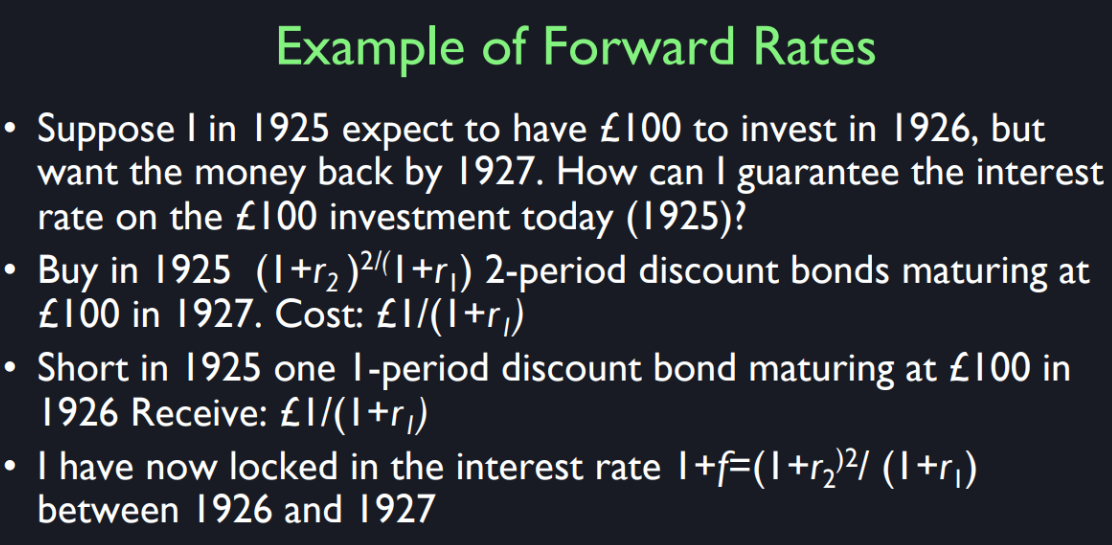

Forward rates are interest rates that can be taken in advance using the term structure. I was writing an article about the term structure of interest rates and I was wondering, "Who invented the concept of forward rate?" And I couldn't figure it out. It's hard to find the first especially back when I was writing when we didn't have the internet. I asked a graduate student, "Can you find out who invented the concept of forward rate? I think it's Sir John Hicks.". So my graduate student went to the library, -the way we used to do these things- and tried to find out. Then he came back to me and he said, "You know, Sir John Hicks is still alive, you could ask Him." So I thought, "I never thought of that. Is he still alive?" So this is back. I don't know like 1980 or something. So I thought, "All right, I'll find his address and I'll mail him a letter." So I typed a letter to him saying, "Did you invent the concept of forward rates?" And I waited about six months and then I get a letter back handwritten with shaky handwriting and so John Hicks said, "Interesting question. Did I invent that concept?" He had shaky handwriting, "I apologize, my health is not good anymore, but I thought I would answer your question." So he went back and he said, "Well, I thought it was, I did a trans- my wife and I did a translation around 1920 of a book by a Swedish economist. I thought it was there, but I went and it's not there." And then he said, he reminisced about conversations he had at coffee hour at the London School of Economics in the 1920s and he said, "Well, maybe somebody brought this up, but I don't know. Maybe I didn't read it." So I put my example here at the coffee hour at the London School of Economics. The year is 1925. This assumes that he got it from some verbal conversation but nobody knows. He's long gone now, we can't ask him again. So here we are sitting at the London School of Economics in 1925 and somebody is saying, "I'm wondering what interest rates I can invest money at in 1926?" That's next year. Remember you got to put yourself back in the time machine here.

So the year is 1925 and you want to invest the money between 1926 and 1927. And he said, "I just wonder what interest rate I can get in 1926?" That's a year in the future. But apparently somebody maybe it was Sir John Hicks at the coffee hour said, "That's a dumb question." Maybe he wasn't so rude. He said, "I can get it today. I can lock it in today." This is 1925, but there's already an interest rate between 1926 and 1927. So we'll call that the forward rate, but that term hadn't been invented. It's amazing how simple concepts don't seem to be known until somebody points them out aggressively. So this is the coffee hour conversation as I'm reconstructing it. This is how you do it.

How do I lock in an interest rate as an investor from 1926 to 1927? I buy in 1925, this number of two-period discount bonds maturing at 100 pounds in 1927. They are two-year bonds. The cost- okay. So, I'm buying this number of them. So if I'm buying this number of them, the cost to me is one pound over one plus r one. And then I have to short in 1925 one- one period discount bond maturing at $100 in 1926. So I receive one over one plus r one pounds. Now think about it. I have locked in an interest rate equal one plus F which is equal to one plus this two- period yield-to-maturity squared all over one plus the one period you have to maturity. And I've locked it in. So this was kind of a showstopper at the coffee hour at the LLC in 1925. This guy thought he was answering unanswerable question and here it is. So that you could pick up today's copy of the London Times and these prices of discount bonds will be listed. I can tell you exactly what the market today is quoting for the 1926 to 1927 investment. So is that- is that clear? It's a little tricky I guess nobody thought to talk in those terms until then.

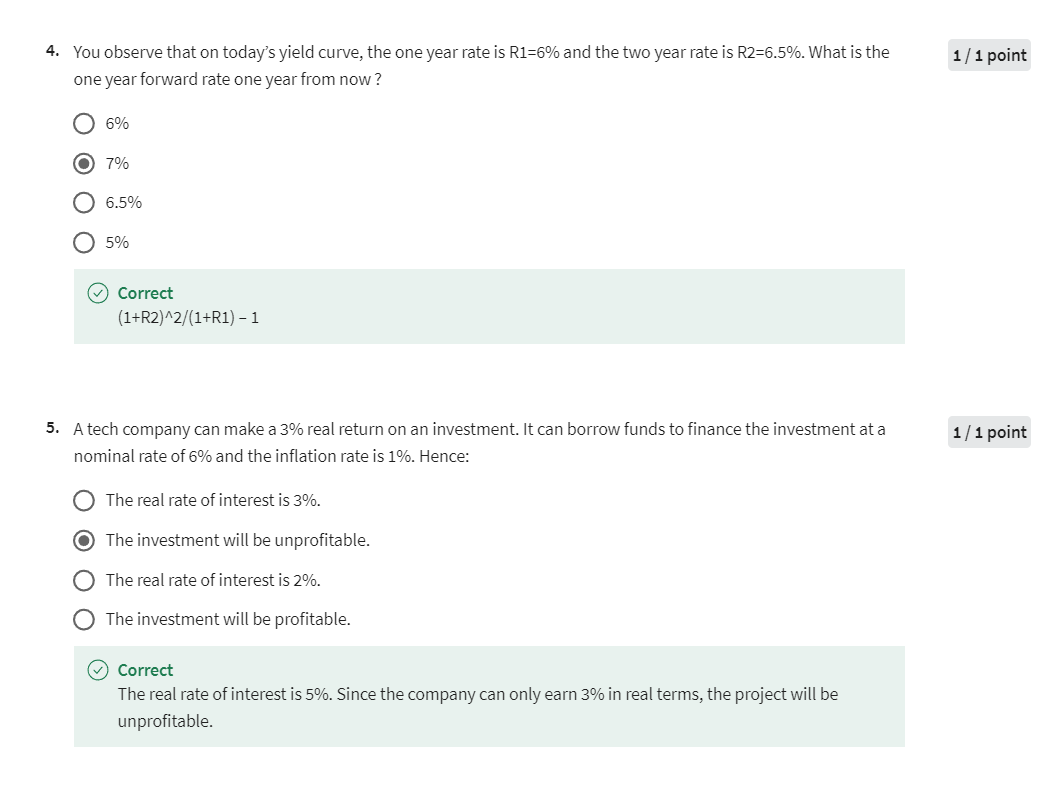

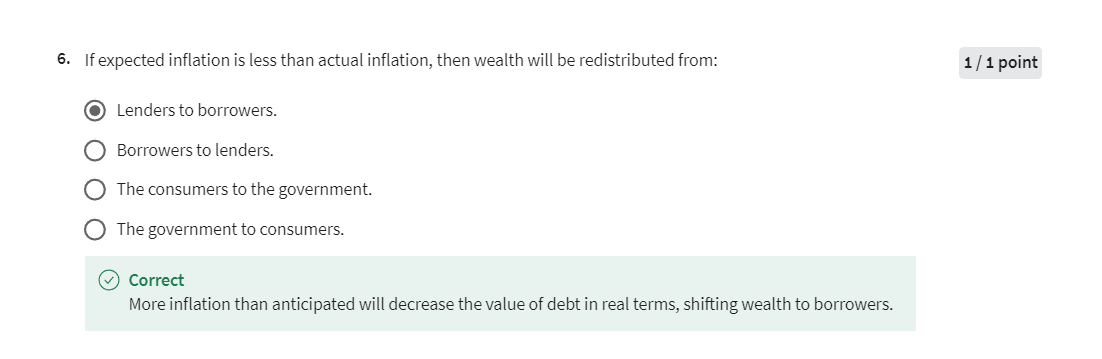

Inflation

I was doing the introduction for the John Bates Clark Medal at

the American Economic Association. And I was telling our own members at

the AEA what did John Bates Clark do that is most distinctive. In 1895,

he wrote a journal article defining what he called the real interest rate. What it is, is the interest

rate corrected for inflation. Now, I did a search to see if anyone

knew of real interest rates before 1895. And I got hits in 1894 and

1893, but nothing before that. So I think it was John Bates Clark

who invented the idea. It's just amazing to me that people

didn't understand forward rates, they didn't understand real rates. To me they seem like

such natural concepts.

So the nominal interest rate, what we've been talking about now,

is quoted in currency. Dollars, Pounds, Renminbi, whatever. But it's not corrected for inflation, and as you know when you have inflation,

the value of the currency declines. The real rate is quoted in

terms of the market basket that underlies the price index,

consumer price index. So just in simple terms,

if you are investing money at 3% for next year and the inflation rate,

consumer price index, is going up at 3% what is your real rate? How much are you making in real terms? Well, it's kind of obvious,

it's zero, right? If I have 3 more on my 100 investment,

but everything that I want to buy has gone up

by 3% then I have the same buying power. So I didn't get anything. So the simple way of describing it is

usually the real rate, this is simplified, the real rate equals the nominal

rate minus the rate of inflation. But actually the formula

is more like this. One plus the nominal rate, or money rate, equals one plus the real rate,

times one plus the rate of inflation. This is an approximation. If you multiply this through, you'll see

that it's missing the cross-product term, the product of R money times I. Which is close to zero.

Another really important invention in

history is the invention of index bonds, which are bonds that pay coupons

defined in real terms and a principle, or one or

the other in real terms. In 1780, I'm attributing

this idea to Paul Revere but I don't know it probably wasn't his idea. But he engraved the bonds,

the first issue of index bonds. I bought one under

Will Goetzmann's influence. I discovered,

I could buy one of these bonds. It'll only cost me $1,000,

and I have it up and it's framed in my office if you

want to come back and see it. Engraved by Paul Revere,

that's pretty neat. But what's even neater about it,

was it was a clever idea. Let's issue bonds whose coupons

are just tied to the inflation rate, so that you know in real

terms what you're getting. The US Treasury did not follow

up on Massachusetts until 1997. So that's 217 year lag between the first issue of indexed bonds in

the United States, and the second. Well, there might have been some minor

issues somewhere in between, but basically that's what happened. So they were called TIPS, they still are,

Treasury Inflation Protection Securities. They were issued in 1997. By 2006,

they were 7% of the national debt. I should update this. They went up more by 2010 or so. I think they're down now. But, they're still big. In the UK they call them

index-linked guilds. They're bigger in the UK, by 2006 they

were 25% of the UK National debt. And France and

other countries have been issuing them. They're still a little controversial,

but they make great sense to me.

Leverage

If a company or

an individual borrows money to buy assets, we say that person or

company is leveraging. Leveraging means you are putting more

money into the asset than you have. You could buy, if you have $100 to

invest you could buy 100 of stocks, or you could buy 200 of stocks and

borrow $100. That makes you in a riskier situation,

but also both up and down. So if you bought $100 worth of stocks and

you're lucky and it doubles in value to $200,

you've made $100. But if you leveraged and

the stock doubles in value, your portfolio goes from 200 minus

100 to 400 minus 100, or $300. So you double your profits. But on the other side of it is

if the stock falls in value. Suppose you bought it unleveraged. You bought $100 worth of stock and

it falls in value by 50%, then you are down to $50, you've lost 50. But if you leveraged and

you borrowed 200 worth of stock and borrowed 100,

then if it falls by 50% you're wiped out. So leveraging increases risks. People look at how

leveraged economies are and wonder about the chaos that might

ensue in a market correction.

For example, China is widely described as a highly leveraged country, it's

gotten worse after the financial crisis. There was a Wall Street Journal article

just the other day pointing out that corporate debt,

borrowing by corporations in China. It is 160% of GDP in China. Whereas in the US, it's only 70%. So that means the Chinese

economy is leveraged. And it could do very well

as a leveraged economy, but it's more vulnerable and

this is a concern. So debt leads to bankruptcy. If you have no debt,

you normally don't go bankrupt because bankruptcy occurs when

your creditors are after you for non-payment and normally, you would

just pay them if you had the money. It's just when you don't have

the money that you are in trouble.

Now I think a very important,

I keep coming back to Irving Fisher. As I say, I'm a little bit biased

because he's a Yale person but I never even met the guy and

I don't know if I would like him. He's kind of a quirky guy. He would invite students over for

dinner at his house, and he would tell them at dinner, you have to chew each bite

100 times before you swallow. Because he thought that was health. Anyone do that? [LAUGH] Be careful to chew your food well? It must have been a little bit odd

having dinner with Irving Fisher. But he was a brilliant economist and he wrote an article in 1933,

in Econometrica, called the Debt-Deflation Model

of Great Depressions. In 1933, prices were falling at a rapid

rate because of the depression. We had huge deflation. And he thought maybe that's why

we are having the depression, and here's his train of thought

as he describes it there. Normally people who borrow

money are the optimists, right? They're borrowing, they're leveraging. They think the stock market will go up or

some other market will go up and they want to get it. And they're willing to take risks. So you have the risk-taking optimists on

one side and then you have the naysayers. They are people who are pessimistic and

risk-averse and they don't want to take

chances as the lenders.

So, what happens when

there's a huge deflation and consumer price index goes down? Well, that magnifies the real

value of the debt, right? If you owe $100 and

the consumer price index falls by 25%, your debt has gone up to about 133,

it's gone up a lot. So what ends up happening in a deflation is that the debtors get beaten down. The optimists have less

wealth in real terms and the pessimists have more because now the

$100 that they loaned is worth a lot more. So he thought this has to be important. You know that people are different. Some people are natural optimist, and

some people are just, not necessarily that they're just pessimistic, but

they just don't want to get into that. They're not entrepreneurial. I don't mean that disparagingly. They're just a different personality. Maybe they're artistic or something else. But then in a depression,

wealth gets distributed towards them so in a weighted sense they

get more votes now. So you've now rewarded the pessimists and

the world is being run by the pessimists. So no wonder we're in

a depression in 1933. Now the recent crisis, that is of 2008/9. That's no quite so recent anymore,

but it's still with us. Did not bring much deflation,

not like 1933. But what it did do is it produced lower

consumer prices than people expected. because inflation often

practically disappeared, and there was some deflation at times. So that means that irrelative to

expectations, wealth had been distributed, redistributed from those who borrowed

money to those who lent money. So it's still true and

it may be important factor to consider. This brings up a question

that I've already alluded to.

Why isn't debt indexed to inflation? Well it isn't. This is the puzzling thing about human

nature, people just don't get it. And it happens again and again that we

have major shifts in the price level and it redistributes debt value

between debtors and creditors. People just don't get it,

I think they're afraid of index numbers, this calculations,

the consumer price index, there's some calculation,

you want my debt to be tied to a formula. So anyway I've already alluded to the fact

that I think we should create an indexed unit of account like they have in Chile or

Mexico or some other countries. So that it would be easier for

people to contemplate indexation, but they dont, this is the real world.

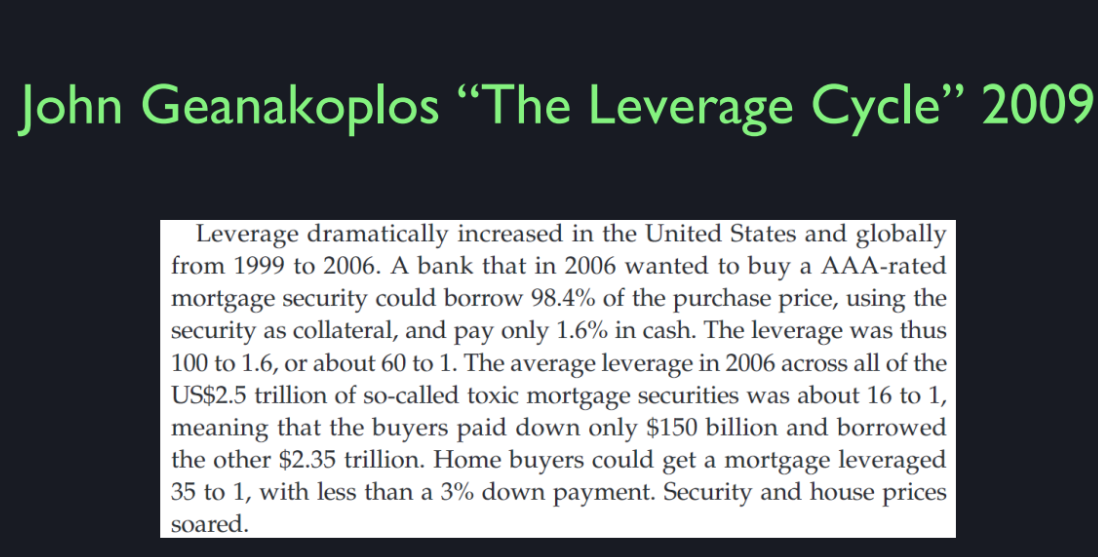

So any time we see unexpected

behaviour of consumer prices it has real effects on the economy. John Geanakoplos here at Yale has written a number of papers

on what he calls the Leverage Cycle. And pointing out that leverage has

varied quite a bit through time, notably recently in

the United States in 2006, just before the financial crisis. Leverage became extremely high,

particularly in the housing market. Banks were allowing people to borrow, typically something like 97% of the value

of the house, to borrow a house. So this leverage, you think anyone

who takes a risky investment and borrows 97% of the money,

that's really a daring thing to do. But everyone was doing that. Anyone who was in that stage of

the lifecycle where you'd buy a house, it's funny how people value, I don't think that people are consistent

at all in their thinking about risk. A view developed in 2006 that the housing

prices are going up, I said before 2006. Housing prices are going up so fast you

can make a lot of money by, in fact you could make a huge amount of money,

percentage-wise, by just buying a house. If you bought a house in 2000,

home prices went up, well, I don't know, I should have this memorized, but

let's say they went up 50% after that, you make 50% on your investment,

it's pretty good. But if you borrow 97% of the money, it's

just astronomical what you could make. People got excited about

leverage because they also had the perception that

home prices don't fall. I know this was out there,

people had this idea. Why do they think that

home prices don't fall? Just the Law of Economics,

house prices never fall? But we know the law is wrong because

in 1933 they were falling rapidly and so, I guess that's beyond

people's memories. So, people got kind of an optimistic

bias just before the financial crisis. And the economy leveraged itself up. It isn't the government that did it. The government if anything,

was leaning against that with regulations. So anyway, so

that's the end of my thoughts. So is debt immoral? I tend not to think of

it at all as immoral. We talked about the Irving Fisher diagram. How the ability to borrow and

lend raises utility. I think that at various times

in life you need money, the extreme case is you need money for

illness, you're sick, you're going to die,

you need expensive treatment. Of course you borrow the money. So lenders are not evil. Even if they lend, we talked about this,

even if they lend for your honeymoon, for a vacation. That's not evil, either. You may know, psychologically, your fiancee needs that if you

want the marriage to succeed. And that's just something you have to do. It's not crazy, it's not self-indulgent. So I think debt is a good thing,

but not always well-managed.

The overall level of debt in the economy (hence leverage) rises in real value because of deflation.

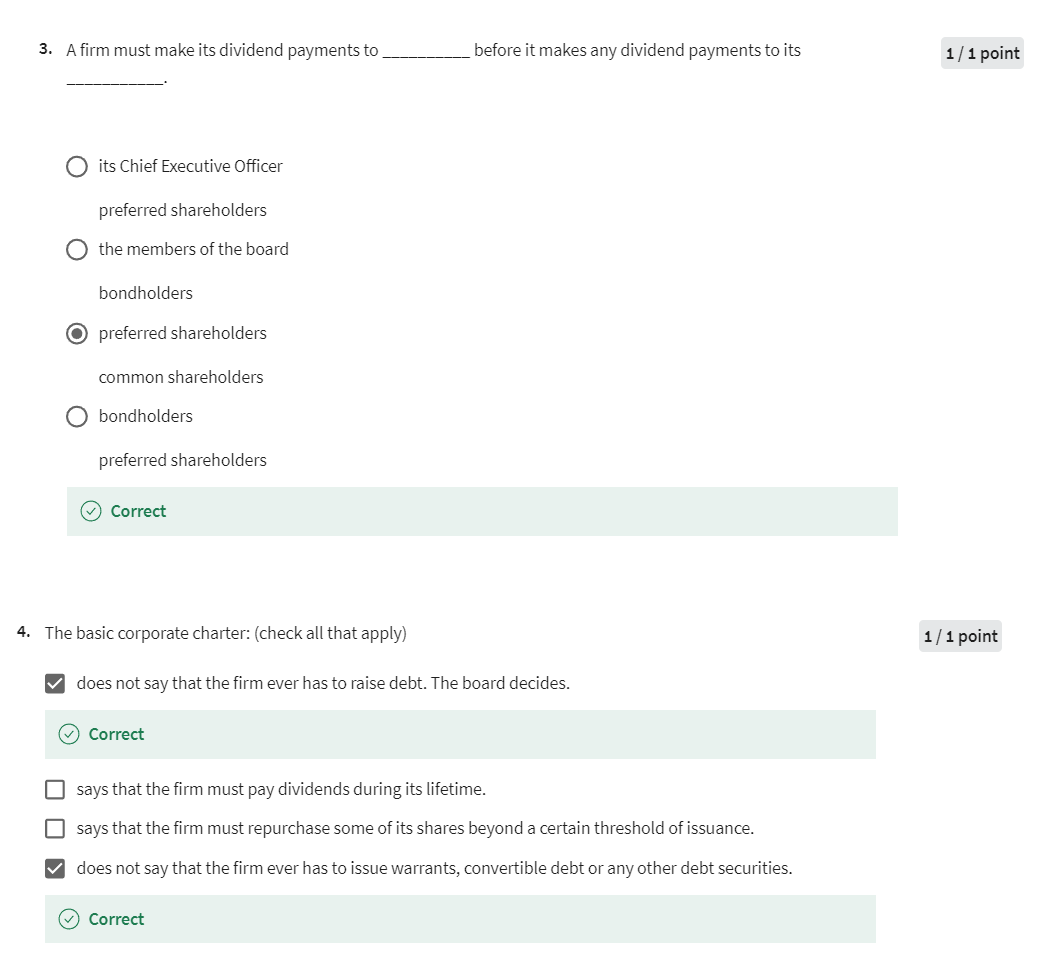

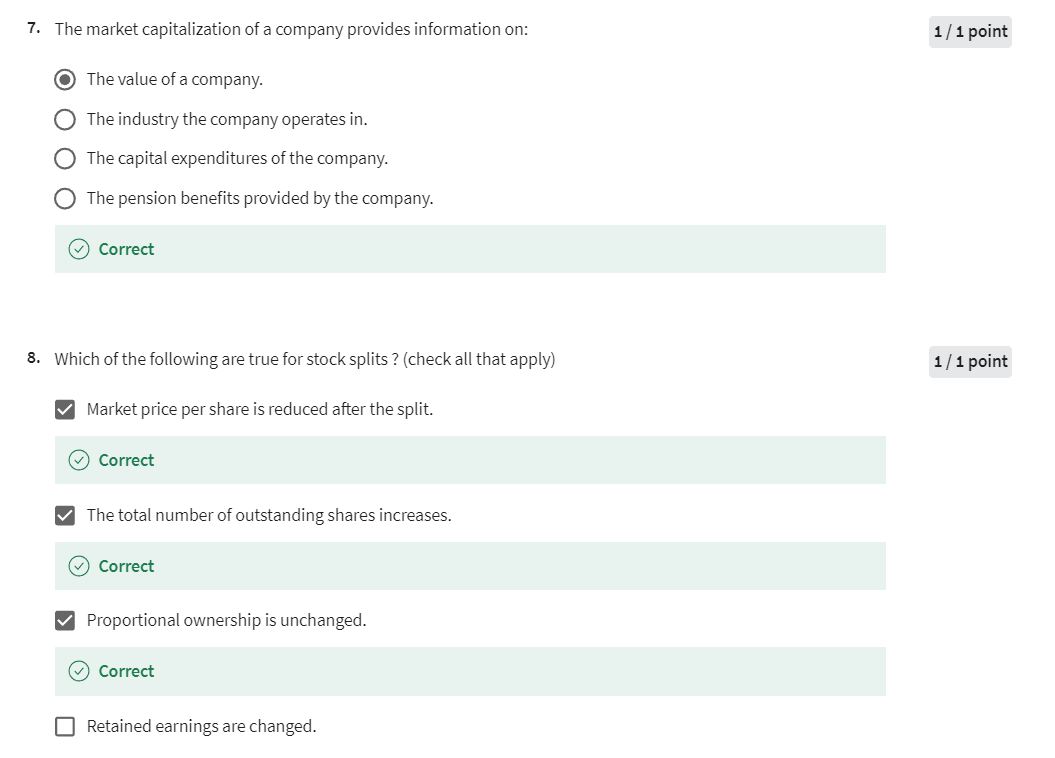

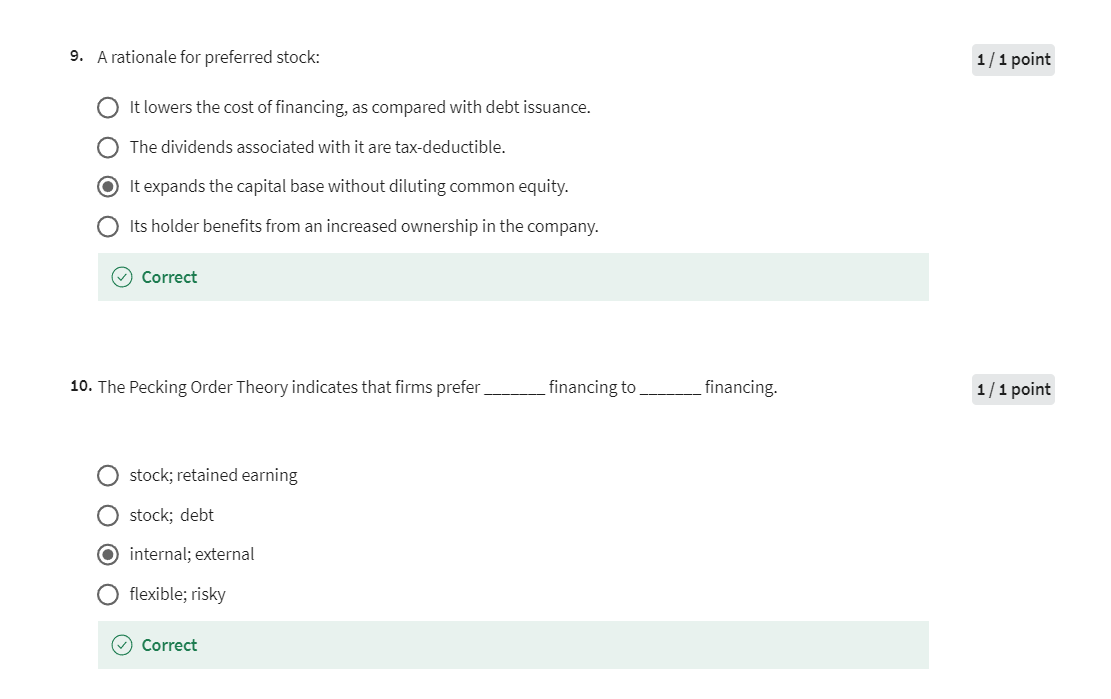

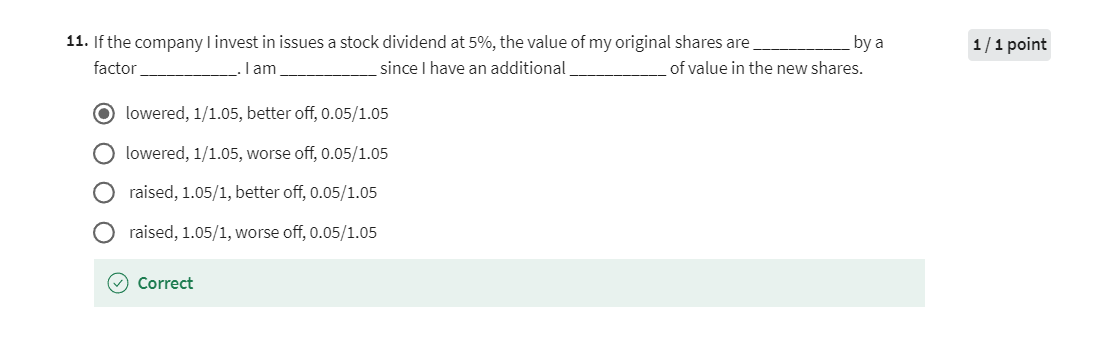

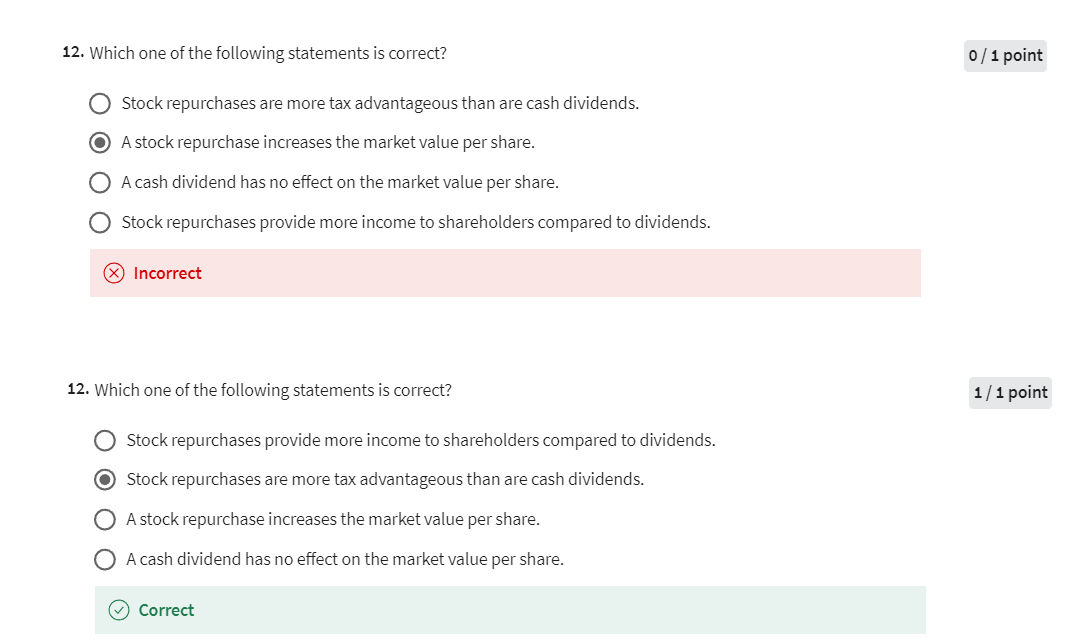

Lesson #8 Quiz

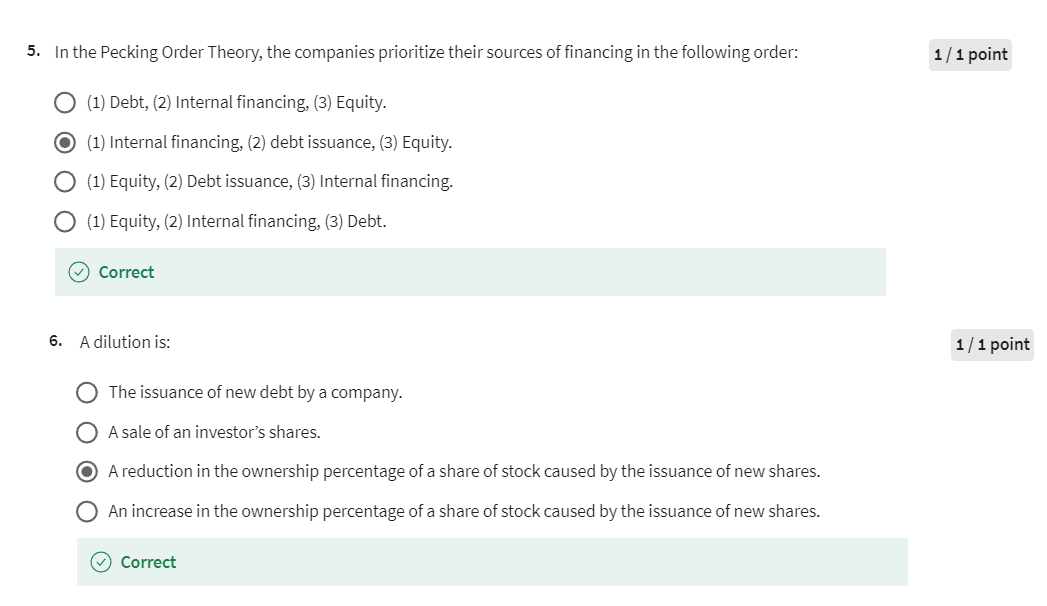

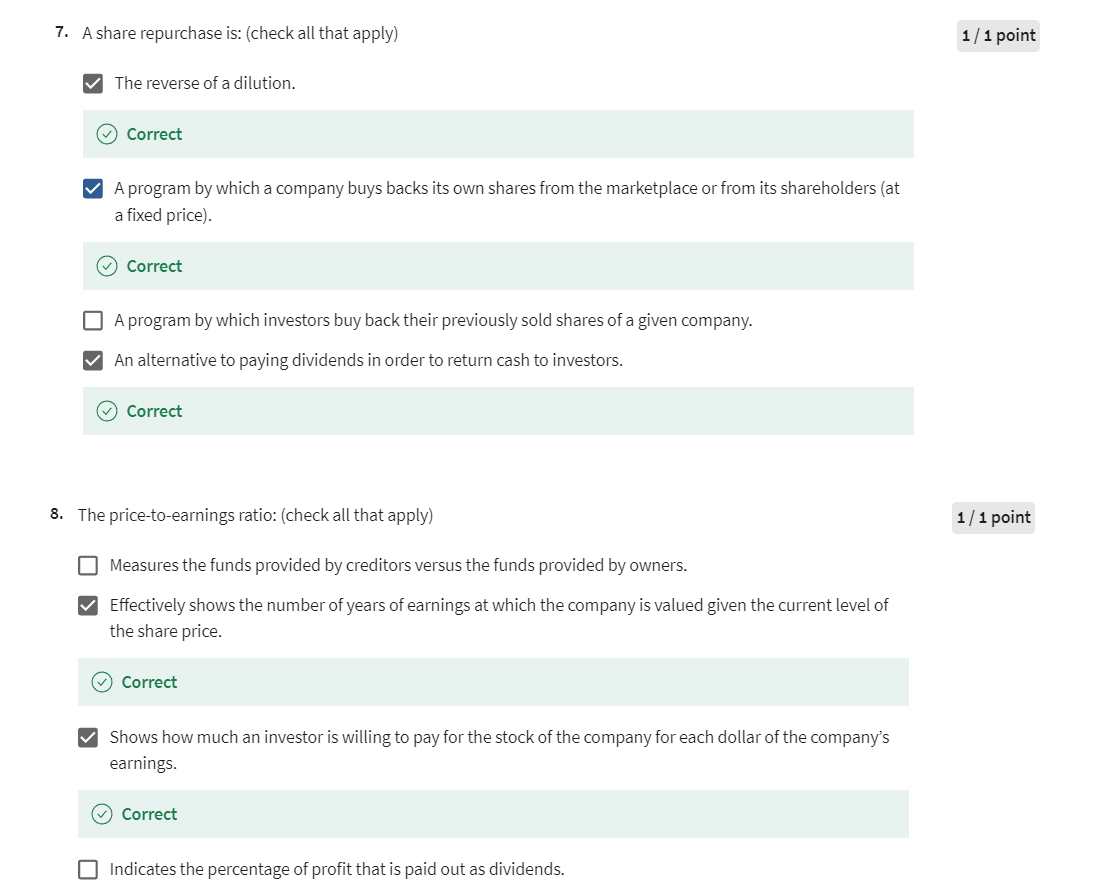

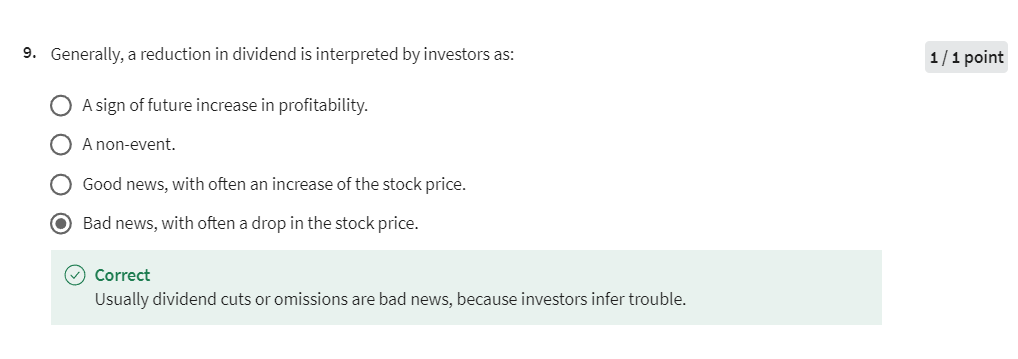

Lesson #9

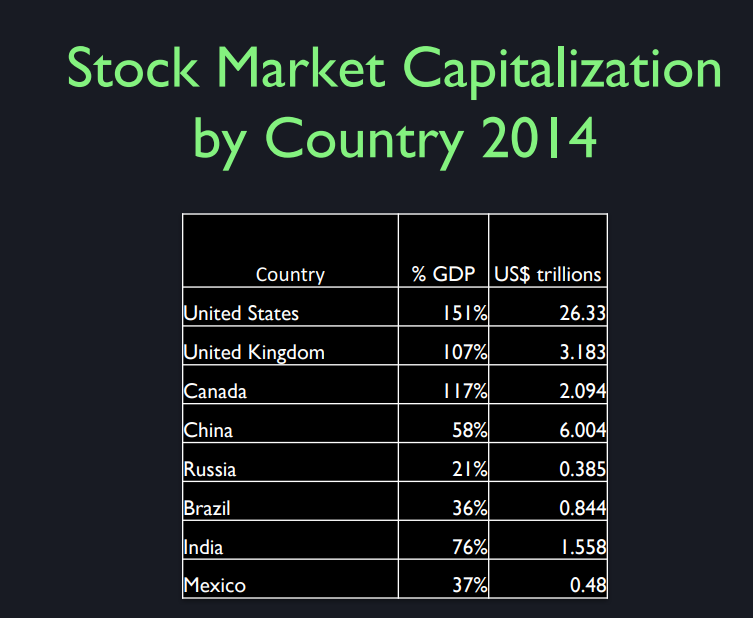

Market Capitalization by Country

Now, we did not invent stocks

in the United States of America. I wanted to show market capitalization. Remember, we defined that market

capitalization is the price per share multiplied by the number of shares,

and this is common stock. I'll define that in a minute. I just took some,

kind of the latest year I could get data, shows the market cap in trillions

of US dollars by country. Just for a random selection

of countries that I picked. And here is the market cap

as a percent of annual GDP. So the United States leads the pack,

for now. United States did not invent corporate

stock, although it was here in the United States that a general

limited liability law was invented. And that may be a head start that this

country got to impetus towards huge stock market valuation. But as of 2014, the market capitalization

of the US stock market was 26 trillion. Actually, it hasn't changed a whole lot

since then, because 2014 was a peak. 2015 was flat, 2016 is down so far, so it's something like that now,

at 151% of GDP. No other country comes close, but

I think if you put the EU together, I didn't do that, that's the European

Union, it comes somewhat close. Here's one EU country. The stock market as a percent of GDP is lower than the US, but

they have a very large GDP. Canada is a little bit less capitalist. See, we're really

capitalists in this country. We have a big stock market,

it's all traded. A lot of this isn't owned

by Americans by the way. The Chinese love the US stock market and

they would invest in it more if there weren't regulations in

China making that difficult. But America is for sale, but I should add,

the US Stock Market is not America. It's a particular thing,

it's a particular contract. It's a claim on earnings

of the corporate sector. And there's much more to this country, and

to any country, than the stock market. So I don't want to overplay it.

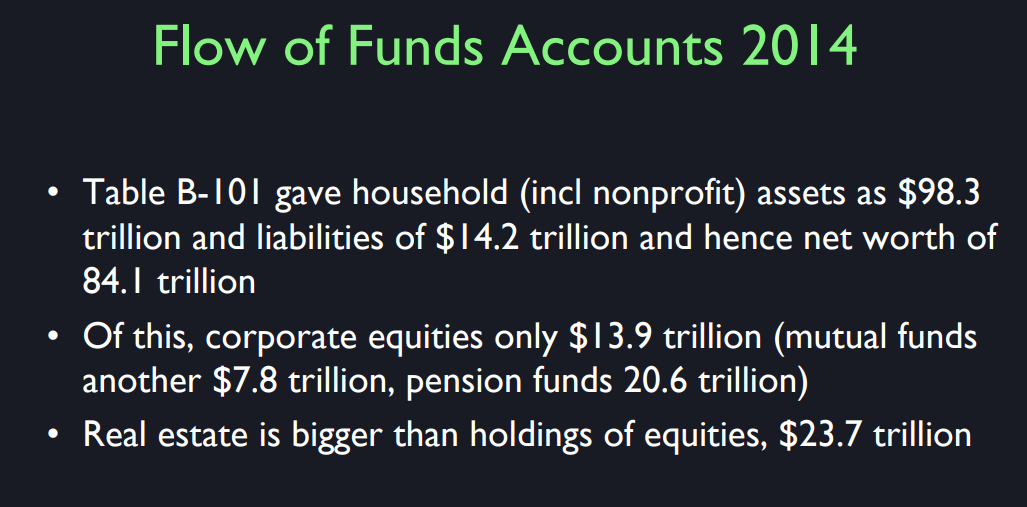

Okay, just to give another perspective,

this is now about the United States. The Federal Reserve Board of Governors has a balance sheet for

households and non profits. They lump in non profits with households,

which I think is unfortunate, but they're small, it's basically households. So what's the total wealth tangible? We're not including human capital. You can compute a present

value of your lifetime income. For each of you, that would be in

the many millions, I'm hoping. [LAUGH] Not for each of you,

some of you won't do that. [LAUGH] But most of you, because you'll

live a long time and earn money for a long time. But what is the tangible assets that we

can quantify and value through markets? According to the Federal Reserve,

as of 2014, these assets were worth $98 trillion US. It asks people to add up everything

they own, their house, their stocks, their bonds, everything. Add that number for every household,

and you get almost $100 trillion. But people don't own it free and

clear, they have liabilities. For example, typically they borrowed money

to buy the house, so they have debt. So we want to subtract

off those liabilities. The total value of those liabilities

in 2014 was 14 trillion. So that leaves the total

net worth of households in the United States at 84 trillion.

That's quite a bit more

than the stock market. Now corporate equities own directly,

now equities, that's the same as stock, common stock. Households own directly 13.9 trillion,

that's less than half of the stock market. They tended to own it in other

forms like mutual funds which are, as of 2014, were almost 8 trillion. What are mutual funds? They are collections of investments

made by a investment company, who then sell shares to the public. Now this includes, I believe, other,

not just corporate stocks, but also it definitely includes bonds and other

investments that mutual funds might make. But it's mostly stocks, and

pension funds, 20.6 trillion. Those are investment companies

that save for your retirement. Your employer typically gives you one. This is not social security, social

security is a government pension fund. But companies also, as a compensation to

their employees, give them pension funds. And the pension funds invest and

typically buy stocks. Now you'ill note that these numbers

add up to more than 26 trillion, which is my market cap for

the stock market. But that's because pension funds also

invest in bonds and other things. And then the balance sheet for the Table

B101 also includes the value of real estate owned directly by households,

that's mostly single family homes. It also includes vacation homes, some

households have investment properties, so the total value of real

estate owned by household. Then I have to say in parentheses,

and non profits is 23.7 trillion. Bigger than the stock market? No, not quite. Bigger than the direct holdings on

the stock market, close to twice as big. So even in America most people are not

that into stock market investing. I think it might be very smart policy

not to buy a home, to rent a home and invest in a broadly diversified portfolio

which that should be less risky. But most people don't do that,

and maybe they have good reasons.

The Corporation

So what is a stock? Well, we first have to think

about the corporation. So the word corporation comes from

the Latin word corpus, meaning body. And what it is,

is an organization that is. Incorporated, that means it's made as

if it has a body, as if it's a person. In fact, the word person in law

typically includes corporations. If you wanted to say an individual

you could say a natural person. [LAUGH] A corporation is

an artificial person. The idea is to create

something that legally has a lot of the rights that individuals do. And traditionally it would be created

by a royal charter, prescription, or act of legislature. More recently it's done according to

procedures that are widely available. In Ancient Rome they had corporations,

they were called publicani. But they were limited, and

they had a stock market. This is what you can read

in the Goetzmann book. The stock market of

Ancient Rome was outdoors on the street in front of one of

the temples in the Roman Forum. And you could go and

buy shares in company. There isn't much data left

about stock prices then. Most of the companies, at least later

in Ancient Rome were of a certain kind. They were tax collectors. The Roman government paid private

companies to collect taxes for them. Why not, right? It's not the way we

normally do things today. But rather than go out after everyone, the

government just hired a company to do it. And those were traded

on the stock exchange. They didn't develop much. I don't know the reason. They didn't have any insurance

companies or shipping companies. Those kinds of activities were

done without incorporation.

Now let's talk about a modern corporation. The modern corporation in

the United States let's talk about a for-profit company like those that

are on the New York Stock Exchange. It's governed by a board of directors

that is elected by the shareholders. So it's called shareholder democracy. Typically one share, one vote. So it sounds like a sensible thing. It's a little bit like

the electoral college in U.S. Constitution for the government. You vote for electors and

then the electors vote for the president. Similarly, you as a shareholder

vote your shares, one share one vote in a company sounds

sensible to elect the board of directors. And then the board of directors

votes on who will be the president. The CEO or president, we now tend to

say CEO, chief executive officer. And companies will also have a president. But the CEO is generally the top,

for instance. So the person, the CEO is hired by

the board, serves as an employee, and has to report to the board of directors. Even non-profits are somewhat like,

they do have a board of directors. And then they hire the president. And there are other structures in Germany,

notably, a company will have two boards,

an Aufsichtsrat and a Vorstand. The Aufsichtsrat is a supervisory board which stands on top of

the whole operation. The Vorstand does the details, manages. Well, it doesn't actually,

it hires people to manage the company. But it's in charge of

day-to-day activities. But it's the same basic idea,

they just divide it into two parts.

Now I've been talking about

for-profit corporations, we also have non-profit corporations. A for-profit corporation is

owned by the shareholders and the shareholders have one vote each. The shareholders have the claim on

the earnings of the company, and have to pay a corporate profits tax. The company has to pay a tax to

the government on its earnings. Non-profit corporations, for example,

Yale University are not owned by anyone. Now you might ask, how can that be? How can it not be owned by anyone? Well, they have a board of directors

called the Yale Corporation. And they have a prevision

where alumni can elect them. Other non-profits would

just be self-perpetuating. That is the directors

appoint their own successors. It sounds a little wild,

because what if the directors get crazy? Then the whole thing could

go down in craziness. But that's the way we leave it. Generally it works. Generally the board appoints other

people who have normally some idealistic commitment to the purposes

of the non-profit. The for-profit exists for shareholders. The non-profit exists for whatever the charter of the non-profit

says, it promotes some cause. For-profits have a price per share. Non-profits are not traded and so they

don't have a price, no price for them.

You mention non-profit

organizations in your lecture, so can you talk about, does non-profit

status means that their revenues should never exceed their costs

to maintain a non-profit status? >> Yeah, non-profit,

maybe it's misleading. It doesn't mean that

they don't make profits. It means that they don't distribute

profits to shareholders. The purpose is not to distribute profits. But they do have a purpose. In a for-profit company, the objectives that are focused on are the shareholders. They take the money and

they do what they want with it. But in a non-profit, the non-profit can

make as much profits as it wants but it keeps them in the company and

spends them on some purpose. A non-profit has to be

defined with a purpose. Because it is doesn't go, otherwise they

would just sit on the money forever. And, in fact,

that kind of thing has happened where non-profits accumulate

huge amounts of money. And people wonder, where's it going to go? Where's it going to be spent? Sometimes non-profits are developed

that have a goal that gets lost later. One famous example is the Shaker Church. That was a Christian church

in the 19th century and they created a foundation and

they accumulated money. But there aren't hardly any Shakers left,

there might be two left in the world. And so the foundation is being

run by people who have to think, well what would I do if I were a Shaker? That is a potential

problem with non-profits. But usually they're defined with

a purpose that will endure and will continue to motivate

their use of the profits.

Shares and Dividends

So now I want to make a very basic

point about corporations and shares. If I give you 1,000 shares

in a company and you wonder, what does that mean that

I own 1,000 shares? You have to ask another question which is,

how many shares at there had standing? So we talked about this before. I'm not up to date on this but it might share of the company is

equal to the total number of shares I own divided by the total number of

shares outstanding for the company. So it's my number

relative to the tutorial. If I own half of the shares outstanding

then I own half of the company. Companies do things called splits

where they will break a share in 2, and call one share another 1.5 shares or

2 shares or whatever. They do that periodically. Why do they do that? It seems that companies think that

there's an optimal price per share that encourages investors look right,

feels right. And so they will change the number

of shares from time to time to try to hit a target for

the price per share. In the United States, by tradition, the target price per share is

something like $30 a share. So suppose your company

has done very well and the price per share which was

originally 30 is now up to 60. Your board of directors may then, someone might bring it up at the board

meeting, we should do a two-for-one split to get our share price back

down to the magic $30 a share. So then you would then send out a letter

to all of your shareholders and saying, we're doubling

the number of shares, and by the way this year, you now have

twice whatever you did before.

Well, I put down my slides. This is essentially meaningless. Other doing is changing

the unit of measurement, it's like going between [FOREIGN] and

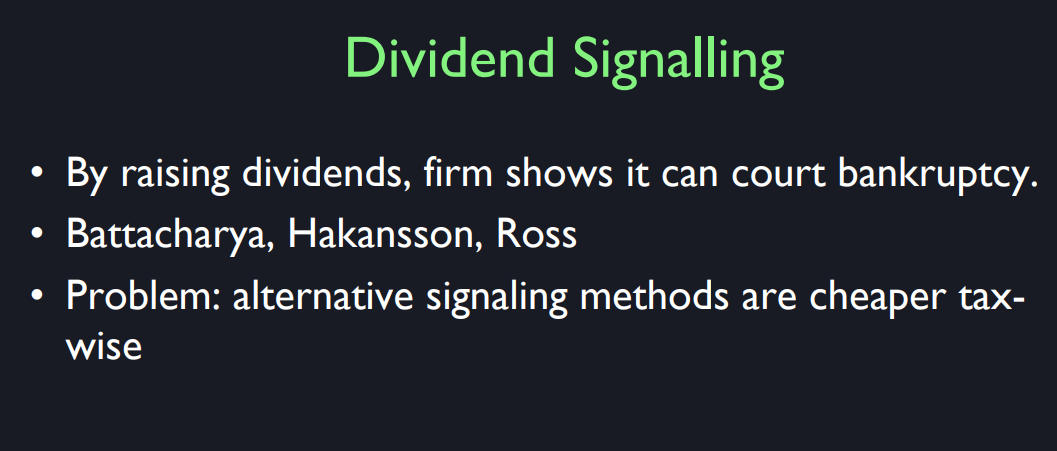

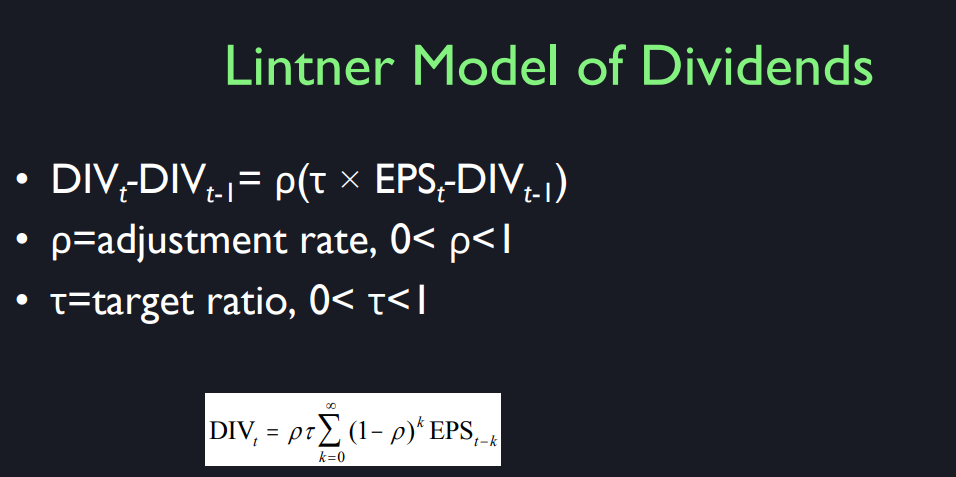

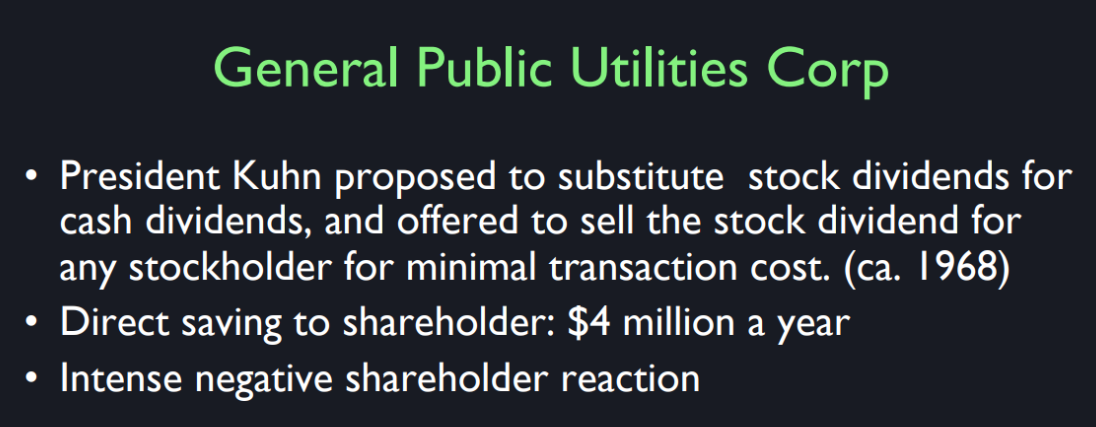

FOREIGN\]. It means nothing. By the way they even do it. Well, why not? One reason they do it is they just think if the share price gets too high, you can't buy a fraction of the share. It gets to expensive, and people like to buy in round lots because the brokers encourage that. About 100 shares. So if it's $30 a share, you can buy an investment round lot for $3,000. But it gets expensive if you don't split. Now one company that doesn't split is Berkshire Hathaway. That's Warren Buffet's company. And it's been selling for thousands of dollars per share. So you can't even buy a round lot unless you a substantially wealthy person. Warren Buffet does that out of some principle. He can do it. Or I should say, his board does that. They can do it because it's all meaningless. But not totally meaningless just that it gets hard device small amount of share. You can buy one share but you can't buy a half of share. So now the company is defined as I said in basic terms, by a board of directors. The company has a constitution, called the Corporate Charter, and the Corporate Charter defines how things are done, but the general principle is guided by state laws. It's state governments that manage. You have to incorporate in a state, which means you choose a state to make your headquarters in. And that state then restricts what you can put into the corporate charter. Delaware is the most popular state for incorporating, because, well, it's the smallest state in the United States and smallest states have an incentive to be very generous to corporations, and they will all move to your state and you end up making money. Big states wouldn't do that because they already have corporations we need to be there. So the corporate law in the state defines the rights and responsibilities of shareholders and the board of directors. Well, it might say something about dividends but it doesn't tell the company what to pay out. This is something that's often forgotten. You buy shares in a company to get dividends. \[SOUND\] A dividend is a distribution of money from the company's earnings to its shareholders. \[SOUND

That's why, in America at least, especially, we're very clear. Why would you buy share in a company? Hey, they pay dividends. It's like interest except its variable. And tends to grow through time. Whereas, debt contracts doesn't grow,

it's just fixed. So you're doing it for the dividends. Remember we had the return on

a corporation has two components, the capital gains which is the

appreciation in the price per share and the dividends. So people tend to talk so

much about the capital gains. The movement of the market,

they forget about dividends. Some people don't even know

there are [LAUGH] dividends. That's actually the whole reason for

being for the stock market. Ideally anyway,

you buy shares to get dividends. And, in fact, if you look at history,

up until recent times, most of the returns you get on

the stock market are in the dividends. People think, well no,

isn't it just that the market has soared? Well, historically, over 100 years,

dividends are more important. The stock market goes up and

down, creates capital gains and capital losses, but

dividends are what it's all about. So companies don't have to pay a dividend

but typically young companies don't. Once they're mature they like

to start paying dividends and it signals to the world that

they're really making money. If you're investing a company

that never pays the dividend, you start to wonder,

is this real or is this a fraud? I never get a penny from them. So once they're into making money, they think it impresses investors

to get dividend checks. All right, I remember my own company. We incorporated in Delaware. My first company,

Case-Shiller Weiss Incorporated. And we didn't have to pay a dividend. I remember we had a board meeting

where we talked about exactly this. We've never paid a dividend. We gave shares to a lot of

our employees as incentive. But someone said,

they don't even believe in it. Nothing has ever happened. So we should pay a dividend. But we didn't. We held on. The employers eventually did

well when we sold the company. They found out that their shares

really were worth something. But we should have started paying

dividends and make it clearer. We didn't.

So when a company pays a dividend,

what happens to the share price? Well, very simple, it drops because

the company used to have the money and now it doesn't. It paid it out. The share price pretty much has to drop

and I don't suppose it always does. Because funny things happen but the basic idea is that a share drops

in value when a dividend is paid. But I have to qualify that. It doesn't drop in value when you get

the check in the mail for you dividend. That would be variable anyway, right? They don't necessarily pay

them out in the exact moment. So a company has to define what

they call an X dividend date. That means, they will pay out

the dividend, this dividend, typically chorally dividend

every three months. They'll pay out this dividend to

shareholders of record on this date. So company values drop routinely

on the ex dividend date. That doesn't mean bad news

about the company at all.

So I had a question about companies and

different dividend payment systems. So some companies like to boast

about they always pay dividends. They never miss it. Why would they want to emphasize this? And what would happen if they had

to cut back on their dividends or they don't miss their

dividends in a period? >> Well, I think this is an essentially

behavioral human question. So the reason they don't want to

miss a dividend is because they think that will harm

the investor support. They don't want to see

their stock price fall. If the investors lose confidence in

the company, these tag price can fall and then the management starts to

worry that that'll be taken over. If the price gets too low, take over, people will think, I'll buy it and

I will shut it down and they'll sell it of all their assets may

be you can get, if it gets low enough. So it's a big fear they don't want

investors to have a bad attitude. So then why would you as an investor

be disturbed if a company didn't pay a dividend? Well, I think it's a sort of

fundamental human miss trust. You don't know that these guys are on

the level, maybe they're crooks or maybe they're not. It's like missing a payment

on your credit card. You have a credit rating that

depends on you actually making these monthly payments. And you could take the attitude, well,

I'll miss it once and I'll pay the fine. What difference does it make? But your credit rating will

go down if you do that. So most people personally think,

I'm going to pay every month, this is something I'm really going to do. And they kind of imagine that it's

like that with dividends with company, if they miss a dividend it means they're

kind of unreliable, untrustworthy, now they didn't have to think that but that

apparently is how a lot of people think. So that's why lots of companies don't

ever want to miss paying a dividend. >> Couldn't missing a dividend also be

a real indication of financial trouble though and maybe that's why investors-

Right, right. >> Why a red flag is raised? >> Yeah, now the thing is that

a dividend is not promised. The corporate law says that they can pay a dividend at the discretion of

the board whether they want to or not. And many companies go years

without paying dividends, but the public might have some preconceived

notions and think it's like my credit card bill and if their not paying,

there's something wrong here. Now they could stop paying a dividend for

perfectly good reasons. Like they want to do something

with it that's more productive, but the investors might not understand. By the way, I don't mean that firms never

miss paying a dividend, I'm just saying that some firms pride themselves

on never having missed a dividend.

Common vs. Preferred

I've already suggested, but I didn't really state it clearly, the difference between common and preferred stock. We've been talking about common stock. Now common doesn't mean plain and not pretty, it means held in common. The word equity refers to common stock as well. I'll come back to that. What's the difference? Preferred stock has a specified dividend which does not grow through time. And like common stock, it doesn't have to be paid. Now again, there might be slight differences in state law. We have 50 different states in the United States and other countries have similar institutes, it's a complicated law. But, typically the deal is this: the company is supposed to pay out a fixed dividend to the preferred stockholders, but it doesn't have to. But, it cannot pay a common stock dividend until it's paid up on its preferred stock dividends. So if they don't pay them, then they have to- if they haven't paid their preferred dividend they've got to make it up eventually.

But in contrast, corporate bonds have a contractual obligation to pay a dividend. So that is, that if the company gets in trouble and it doesn't- as I say dividend, a coupon, on the bond. If a company gets in trouble and doesn't pay out its coupon the shareholders can come back and sue, force the company into bankruptcy. Preferred stockholders can't do that otherwise they're kind of like corporate bonds. During the financial crisis 2000, 2008, 2009, the U.S. government got a lot of preferred shares in companies for bailing them out. The U.S. government didn't want to get common shares, it wanted to get paid back. It didn't want to push them into bankruptcy by creating a new form of debt. So the U.S. government got preferred stock in the company. Why didn't they get common stock? Hey, this is America. The U.S. government, if it were to be buying common stock this would be socialism. The government would be owning parts of companies and they didn't want to do that. So they bought preferred stock. So for example the U.S. government and the Canadian government I think had a lot of preferred shares in General Motors.

Corporate Charter

Now, the basic corporate

charter emphasizes that all common shareholders

are treated equally. They don't have to pay out dividends to

them, but if they do pay out dividends, it has to be every share gets the same. And that's where the word equity comes in,

it's equality of shareholders. Does not have to pay dividends,

it doesn't ever have to pay dividends. But you trust that the Board will

pay dividends, because the other shareholders want the money, they can't

get at it without paying you too. The firm can also repurchase shares

instead of paying a dividend. No law saying that they have to,

they can both issue new shares and they can repurchase shares,

the Board decides. There's also other kinds

of corporate liability, warrants which are a form of option,

convertible debt. They can do whatever they want, but the fundamental thing that

ties it down is that all shareholders have one vote,

and they elect the Board. Now there are critics of

shareholder democracy.

Notice notably Berle and Means wrote

a book in 1933, that was very influential. Arguing that while you've

described a system of corporate governance

that sounds plausible, and probably does work for little companies,

but it might not work for big companies. Well I know when I set up my own

little company, Case Shiller Weiss, there were three of us, and

well we had one more major shareholder. We got together, and

it was very clear that we voted and things happened because we were involved. So the democracy, it just seemed

perfectly natural and functional. But Berle and Means thought that it

doesn't work so well for big companies. The same reason may be why voting, when there are millions of people voting,

doesn't work so well. So I know what you think whether,

do you vote? Okay, as you go to the voting booth in an

election, does it ever occur to you that my vote doesn't matter unless the rest

of the people are equally tied, right? If exactly half vote for one candidate and

exactly half vote for the other candidate that it's tied and my vote would decide,

otherwise my vote doesn't do anything. So what's the probability that

my vote is the deciding vote? Well if there's millions of people,

the probability must be miniscule, so if you were really rational,

you wouldn't vote. But people still vote in elections, and

this must be out of some sort of patriotic feeling or a sense of obligation.

But when it comes to corporations,

those senses aren't so, you don't feel patriotic for

a corporation. So and a corporation has an election,

why do I even bother. We're holding diversified portfolios,

aren't we? So, I've got a hundred different stocks, I can't keep up with how

they're all being managed. [INAUDIBLE] during election and

vote my share. I'm only a tiny, tiny fraction,

so why should I do that? So Berle and Means said that, while in practice we have

shareholder democracy, in practice the democracy is imperfect. It's really self-perpetuating

Boards of Directors. So their book was extremely

important historically. And what it led to is new regulation that

tried to allow for takeovers of companies. What Berle and Means said, is there's