Modern operational systems are often evaluated by the richness of their features or the elegance of their workflows. Yet, many such systems degrade over time: they become difficult to govern, hard to explain, and increasingly dependent on manual coordination. This failure pattern is not accidental. It reflects a deeper structural problem---operations systems are commonly designed around flows and functions, while real operational complexity is semantic in nature.

This essay argues that sustainable operational systems must be semantic-driven . Their primary design object should not be workflows, APIs, or automation chains, but task semantics: what actions mean in the real world, how facts are established, how decisions are justified, and how responsibility is assigned. Without this semantic backbone, systems may execute efficiently in the short term but will inevitably lose controllability, auditability, and evolutionary capacity.

The Limits of Flow-Centered Design

Flow diagrams and process models are attractive because they provide an illusion of order. They emphasize sequence, dependency, and completion. However, real operations are not linear narratives; they are networks of concurrent actions, partial failures, negotiations, and compensations.

The most damaging limitation of flow-centered design is not technical but epistemic:

it hides complexity rather than organizing it. Cross-boundary coordination, exception handling, and responsibility allocation are pushed outside the formal system---into informal rules, synchronous calls, or human intervention. As a result, when disputes arise or systems fail, there is no authoritative way to answer basic questions such as:

-

What actually happened?

-

Why was this choice made?

-

Who was responsible for approving or overriding it?

A system that cannot answer these questions is operationally brittle, regardless of how advanced its automation appears.

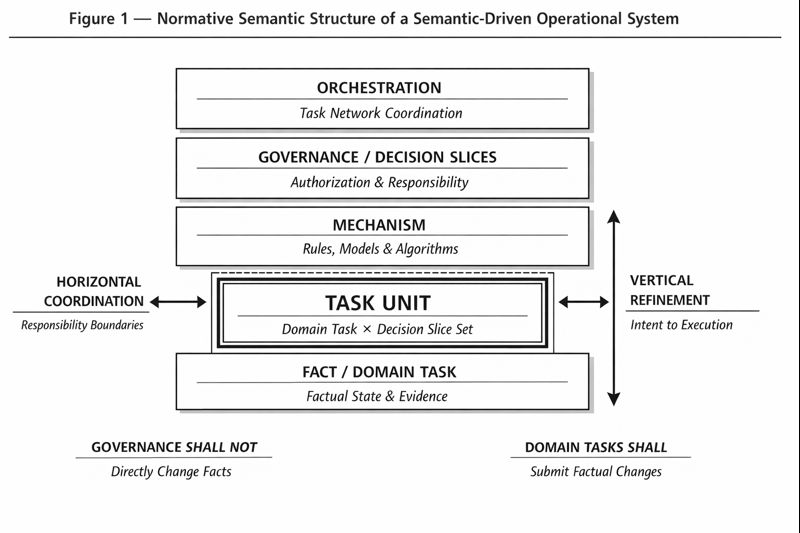

Task Units as the Proper Semantic Primitive

To overcome this limitation, operational reality must be structured around task units , not flows. A task unit is not merely a step in a process; it is a meaningful action in the real world. It has intent, a lifecycle, success and failure criteria, and---critically---evidence.

The central claim is that task units are the smallest units of operational meaning, not functions or transactions. They are closer to sentences than to instructions: they describe what was attempted, what was achieved, and under what conditions.

This shift has profound implications. When tasks, rather than flows, become the primary design object, systems stop pretending that all complexity can be flattened into sequence. Instead, concurrency, waiting, retries, and compensations become first-class concepts rather than edge cases.

Separating Facts from Decisions Is Not Optional

One of the most common structural errors in operational systems is the conflation of fact progression and decision-making. Systems either:

-

silently embed governance decisions into procedural logic, or

-

elevate every conditional branch into a formal approval process.

Both extremes are harmful.

A semantic-driven system must explicitly distinguish between:

-

Domain tasks, which advance factual state in the world, and

-

Decision slices, which capture moments where authority, responsibility, and justification are required.

This separation is not bureaucratic---it is protective. It ensures that facts are not mutated without accountability, and that accountability does not paralyze execution. Decisions constrain what may happen; domain tasks determine what did happen.

Crucially, decisions do not directly change reality. They authorize, prohibit, or redirect. Reality changes only when domain tasks consume decisions and submit verifiable outcomes. This boundary is essential for auditability and long-term trust in the system.

Complexity Has Structure, Not Just Scale

Another core argument is that operational complexity is not a single dimension that grows with system size. It has at least two independent sources:

-

Horizontal coordination complexity, arising from crossing organizational, contractual, or system boundaries.

-

Vertical refinement complexity, arising from decomposing intent into executable detail.

Treating these as interchangeable leads to systematic misdesign. Governance mechanisms cannot solve refinement problems, and algorithms cannot resolve accountability conflicts. A semantic-driven architecture makes these dimensions explicit, allowing design effort to be focused where complexity truly originates.

This perspective reframes architecture debates. Instead of arguing about tools or platforms, teams can ask a more productive question:

Is our difficulty primarily one of coordination, or one of refinement?

The answer determines which semantic structures must be strengthened first.

Governance Is the Entry Point for Evolution

Operational systems are not static artifacts; they are living systems embedded in changing organizations and environments. The ability to evolve safely depends not on predictive modeling alone, but on institutional memory.

Semantic-driven systems preserve this memory through:

-

fact chains that record what occurred,

-

decision chains that record why choices were made and by whom,

-

mechanism versions that record how conclusions were derived at the time.

Governance, in this sense, is not friction---it is the feedback interface through which systems learn. Without it, optimization becomes guesswork, and automation becomes a liability rather than an asset.

Conclusion: Execution Without Semantics Is Unsustainable

The fundamental thesis of semantic-driven operations design is simple but demanding:

An operational system must be able to explain itself before it attempts to optimize itself.

Flows can execute, functions can compute, and automation can accelerate---but only semantics can sustain meaning, responsibility, and trust over time. By grounding systems in task units, separating facts from decisions, and making complexity explicit rather than implicit, we move from systems that merely run to systems that can be governed, audited, and evolved.

In an era of increasing automation and intelligent decision-making, this semantic foundation is not a luxury. It is the precondition for scale without loss of control.