数据降维:PCA主成分分析与UMAP算法的详细解读与实现

ming | 2025.12

在讲解具体的数据降维方法之前,我们必须要明白,什么是数据降维。我们可以从一个熟悉的场景来理解它。

假设你要买一台新手机,面对琳琅满目的品牌和型号,你会如何做出决定? 如果是我的话,我可能会去看评测视频或文章,下意识地聚焦于几个核心指标:CPU性能、屏幕素质、电池容量、拍照效果和价格。然后我会综合这些因素来选择一款手机。

现在,想象你拿到了一张极为详尽的手机参数总表,上面罗列了每一款在售机型的所有数据:

erlang

CPU型号,屏幕尺寸(英寸),电池容量(mAh),实测续航时间(小时),充电功率(W),从10%充满电所需时间(分钟),屏幕刷新率(Hz),内存与存储配置(GB),主摄传感器型号,整机重量(g),电源管理系统(PMIC)型号,射频前端(RFFE)模块,音频编解码器型号,搭载的各类传感器,基带芯片版本,图像信号处理器(ISP)型号,参考价格(元)...上面的这些信息对你挑选手机有帮助吗?当然有,但是太冗余了,有很多信息是没有必要的,其中像"射频前端(RFFE)"这类极其底层的硬件参数,对绝大多数消费者而言,其专业程度和决策相关性都极低,几乎等同于噪声。我相信应该没有人会通过一台手机的射频前端型号来选择手机。这时候,我们就要对这个表进行数据降维了。

数据降维的本质,是对原始数据做一次智能的"信息提纯" 。它并非随意丢弃,而是通过数学变换,将这张庞杂的表格转化为我们能够直观理解 和高效使用的"核心指标看板";比如上面的"电池容量"和"续航时间",这两个特征是高度相关的;再比如诸如"射频前端","PMIC"这些特征,可能对最终决策影响很小,大多数人都不会关注这个。因此我们可以将这些多余的特征维度去除,只留下最能对我们挑选手机有用的特征即可,这就是数据降维。

在机器学习领域中,一个数据集的特征(维度)动辄成百上千,高维数据不仅会增加计算负担,还容易引发"维度灾难",导致模型过拟合、泛化能力下降。(因为有很多特征之间高度相关,还有很多特征对当前任务没有什么影响,属于噪声)。

再举一个简单的例子,有如下的一张表:

| 水果 | 特征1 | 特征2 | 特征3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 苹果 | 0.12 | 0.25 | 0.21 |

| 菠萝 | 0.50 | 0.98 | 0.62 |

| 香蕉 | 0.01 | 0.19 | 0.10 |

| 橘子 | 0.32 | 0.63 | 0.43 |

| 橙子 | 0.64 | 1.24 | 0.79 |

表面上,每个水果由三个特征定义,但实际上,所有有效信息都蕴含在"特征1"这一条轴上。特征2和特征3不过是特征1经过简单线性变换后的"影子"。

实际上,特征2 ≈ 特征1 × 2,特征3 ≈ 特征1 + 0.1。这意味着三个特征中存在严格的线性关系,信息是冗余的。

因此在数据降维的时候完全可以把特征2与3删去。

这个例子揭示了数据降维中一个最经典、也最强大的思想:在看似复杂的高维数据中,往往存在着少数几个"隐藏"的主轴,大部分数据变化都沿着这些主轴发生。找到它们,就相当于抓住了数据的本质结构。

当你对数据降维的必要性与核心思想有了基本了解后,下面就开始讲解数据降维领域最经典的算法------主成分分析(PCA),然后用代码实现一遍这个算法。最后再讲解使用一下现代主流数据降维算法UMAP。

注意:下面的内容需要你有一定的线性代数基础和numpy基础才能理解,否则会很难搞清楚PCA究竟做了一件什么事。

一. PCA主成分分析

要深入理解PCA主成分分析,我们首先需要掌握线性代数中的一个核心概念------SVD奇异值分解。如果你对这个概念还不熟悉,不用担心,接下来我会详细解释什么是SVD。

SVD奇异值分解是线性代数中一个极其重要的数学工具,它描述的是,对于任意一个矩阵 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> A A </math>A(形状为 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> m × n m \times n </math>m×n),都能分解成三个矩阵的乘积 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> A = U S V T A=USV^{T} </math>A=USVT。其中:

- <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> U U </math>U是一个 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> m × m m \times m </math>m×m的正交矩阵( <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> U T U = I U^T U = I </math>UTU=I)

- <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> V T V^{T} </math>VT是一个 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> n × n n \times n </math>n×n的正交矩阵( <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> V V T = I V V^T = I </math>VVT=I)

- <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> S S </math>S是一个 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> m × n m \times n </math>m×n的对角矩阵,对角线上的元素称为奇异值,均为正数且通常按降序排列

注意,任意形状的矩阵都可以进行SVD奇异值分解,但是为了方便起见,这里就认为矩阵 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> A A </math>A是一个方阵(形状为 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> n × n n \times n </math>n×n)

<math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML" display="block"> A = U S V T = U [ s 1 0 0 0 0 s 2 0 0 ⋮ ⋮ ⋱ ⋮ 0 0 0 s n ] V T , ( s 1 ≥ s 2 ≥ s 3 ≥ . . . ≥ s n ≥ 0 ) A = USV^{T} = U\begin{bmatrix} s_{1}& 0& 0& 0\\ 0& s_{2}&0 &0 \\ \vdots & \vdots & \ddots &\vdots \\ 0 & 0 & 0 &s_{n} \end{bmatrix} V^T ,\space\space\space (s_{1}\ge s_{2}\ge s_{3}\ge ...\ge s_{n}\ge 0 ) </math>A=USVT=U s10⋮00s2⋮000⋱000⋮sn VT, (s1≥s2≥s3≥...≥sn≥0)

至于为什么任何一个矩阵能分解成三个特定的矩阵 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> U , S , V T U,S,V^{T} </math>U,S,VT的乘积,这就是数学问题了,SVD奇异值分解有着坚实的数学基础,如果你对证明过程感兴趣,可以自行在互联网上检索。

这里我们亲手实践一下,python的numpy库中有现成的SVD奇异值分解的函数,可以直接调用。

python

import numpy as np

# 定义矩阵A

A = np.array([[2.0, 3, 5],

[7, 11, 13],

[17, 19, 23]])

# 进行SVD奇异值分解

U, s, V_t = np.linalg.svd(A)

print(U)

print(s)

print(V_t)

python

# 输出

# U

array([[-0.15323907, -0.44072023, -0.8844679 ],

[-0.46548171, -0.75732959, 0.458016 ],

[-0.87169063, 0.48188958, -0.08909473]])

# s

array([39.37043356, 2.28397225, 0.86742829])

# V_t

array([[-0.466939 , -0.56240524, -0.68239894],

[ 0.87977217, -0.21755265, -0.42269583],

[-0.08926865, 0.79772877, -0.5963723 ]])注意,上面分解的 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> s s </math>s之所以是一个一维数组而不是我们上面说的对角矩阵,是因为numpy出于存储效率的考虑,只存储有用的部分,因为其它地方都是0,没有必要存储,只存储对角线上的元素,大大提高存储效率。

现在,我们验证一下numpy进行的SVD矩阵分解是否正确,我们试试将 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> U , S , V T U,S,V^{T} </math>U,S,VT进行矩阵乘法,看看结果是不是 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> A A </math>A。

首先,把 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> s s </math>s变成对角矩阵 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> S S </math>S

python

# 将s变为二维对角矩阵

S = np.zeros(A.shape)

S[: len(s), : len(s)] = np.diag(s)

print(S)

# 输出

array([[39.37043356, 0. , 0. ],

[ 0. , 2.28397225, 0. ],

[ 0. , 0. , 0.86742829]])

python

print(U @ S @ V_t) # 这里的@符号是矩阵乘法的意思

# 输出

array([[ 2., 3., 5.],

[ 7., 11., 13.],

[17., 19., 23.]])完美还原! 我们可以看到,通过SVD分解后再重新组合,我们得到了原始的矩阵A。这验证了SVD分解的正确性。

虽然我们在示例中使用了numpy的linalg.svd函数,但在处理大规模数据时,我们通常不会直接使用这个函数来实现,因为它很占内存,并且计算量非常大,小型矩阵还好,但是我们实际应用中要处理的矩阵都是成百上千维的。

接下来,我们换一个视角,将矩阵 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> U U </math>U 的每一列看成一个列向量 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> p i ⃗ \vec{p_i} </math>pi ,将矩阵 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> V V </math>V 的每一列看成一个列向量 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> q i ⃗ \vec{q_i} </math>qi ,那么上面的式子就可以重新表述为:

<math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML" display="block"> A = U S V T = [ p 1 ⃗ , p 2 ⃗ . . . , p n ⃗ ] [ s 1 0 0 0 0 s 2 0 0 ⋮ ⋮ ⋱ ⋮ 0 0 0 s n ] [ q 1 ⃗ T q 2 ⃗ T ⋮ q n ⃗ T ] A = USV^{T} = [\vec{p_{1}},\vec{p_{2}}...,\vec{p_{n}}]\begin{bmatrix} s_{1}& 0& 0& 0\\ 0& s_{2}&0 &0 \\ \vdots & \vdots & \ddots &\vdots \\ 0 & 0 & 0 &s_{n} \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} \vec{q_{1}}^{T}\\ \vec{q_{2}}^{T}\\ \vdots \\ \vec{q_{n}}^{T} \end{bmatrix} </math>A=USVT=[p1 ,p2 ...,pn ] s10⋮00s2⋮000⋱000⋮sn q1 Tq2 T⋮qn T

现在,我们将这个式子进行展开化简,利用矩阵乘法的分配律,将其拆解为一系列"多项式"之和:

<math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML" display="block"> A = s 1 p 1 ⃗ q 1 ⃗ T + s 2 p 2 ⃗ q 2 ⃗ T + . . . + s n p n ⃗ q n ⃗ T A = s_{1}\vec{p_{1}}\vec{q_{1}}^{T} + s_{2}\vec{p_{2}}\vec{q_{2}}^{T} + ... + s_{n}\vec{p_{n}}\vec{q_{n}}^{T} </math>A=s1p1 q1 T+s2p2 q2 T+...+snpn qn T

请注意,由于列向量 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> p i ⃗ \vec{p_i} </math>pi 的形状为 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> ( n , 1 ) (n,1) </math>(n,1),行向量 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> q i ⃗ T \vec{q_i}^T </math>qi T 的形状为 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> ( 1 , n ) (1,n) </math>(1,n),因此每一项 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> p i ⃗ q i ⃗ T \vec{p_i}\vec{q_i}^T </math>pi qi T 都是一个 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> n × n n \times n </math>n×n 的矩阵。而每个奇异值 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> s i s_i </math>si 则充当了对应子矩阵的权重系数 ,它的大小衡量了该子矩阵在重构原始矩阵 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> A A </math>A 时的重要性。

由此,我们发现一个重要的洞察:一个复杂的矩阵 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> A A </math>A,可以被分解为一系列简单(秩为1)矩阵的加权和。

那么,一个自然的想法就产生了:既然每个子矩阵的贡献由权重 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> s i s_i </math>si 决定,我们是否可以舍弃那些权重非常小的子矩阵,而只用剩下的主要部分来近似原矩阵 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> A A </math>A 呢?毕竟,权重小的项对最终合成结果的"影响"微乎其微。

答案是肯定的,而这正是SVD用于数据降维的核心思想。 由于奇异值满足 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> s 1 ≥ s 2 ≥ s 3 ≥ . . . ≥ s n ≥ 0 s_{1} \ge s_{2} \ge s_{3} \ge ... \ge s_{n} \ge 0 </math>s1≥s2≥s3≥...≥sn≥0,通常它们会快速衰减。这意味着前几个奇异值往往包含了矩阵中绝大部分的信息或"能量"。因此,我们可以只保留前几个最大的奇异值及其对应的子矩阵,来得到一个非常优秀的近似。

<math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML" display="block"> A ≈ s 1 p 1 ⃗ q 1 ⃗ T + s 2 p 2 ⃗ q 2 ⃗ T + s 3 p 3 ⃗ q 3 ⃗ T A \approx s_{1}\vec{p_{1}}\vec{q_{1}}^{T} + s_{2}\vec{p_{2}}\vec{q_{2}}^{T} + s_{3}\vec{p_{3}}\vec{q_{3}}^{T} </math>A≈s1p1 q1 T+s2p2 q2 T+s3p3 q3 T

从矩阵运算的角度看,这个近似过程等价于将三个分解矩阵 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> U , S , V T U, S, V^T </math>U,S,VT 同时进行"截断":

<math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML" display="block"> A ≈ [ p 1 ⃗ , p 2 ⃗ , p 3 ⃗ ] [ s 1 0 0 0 s 2 0 0 0 s 3 ] [ q 1 ⃗ T q 2 ⃗ T q 3 ⃗ T ] A \approx [\vec{p_{1}},\vec{p_{2}},\vec{p_{3}}]\begin{bmatrix} s_{1}& 0& 0\\ 0& s_{2}&0 \\ 0 & 0 & s_{3} \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} \vec{q_{1}}^{T}\\ \vec{q_{2}}^{T}\\ \vec{q_{3}}^{T} \end{bmatrix} </math>A≈[p1 ,p2 ,p3 ] s1000s2000s3 q1 Tq2 Tq3 T

如果你不相信,我们可以做一个实验。

我们知道,一张灰度图像本质上就是一个数值矩阵,每个像素值通常在 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> 0 0 </math>0 到 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> 255 255 </math>255 之间。

这里,我使用一张大小为 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> 640 × 640 640 \times 640 </math>640×640 的灰度图像 Frieren.jpg。

现在,我用Python读取这张图像,得到一个形状为 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> ( 640 , 640 ) (640, 640) </math>(640,640) 的矩阵 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> A A </math>A,并对其进行奇异值分解(SVD),得到 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> U , S , V T U, S, V^T </math>U,S,VT。

python

import numpy as np

from PIL import Image # 需要引入pillow库,用来处理图像

# 读取灰度图像

def read_grayscale_image(image_path):

img = Image.open(image_path).convert('L')

img_array = np.array(img)

return img_array

image_path = './Frieren.jpg'

A = read_grayscale_image(image_path)

# 进行完整的SVD分解

U, S, Vt = np.linalg.svd(A)不推荐使用上面的代码进行SVD分解,效率非常低,下文会有更加高效的SVD分解实现

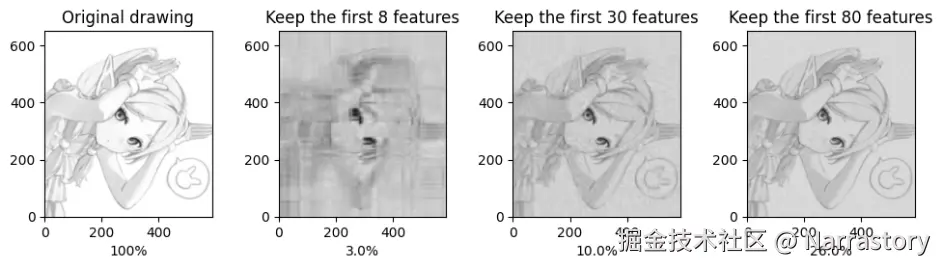

由于 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> A A </math>A 是 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> 640 × 640 640 \times 640 </math>640×640 的矩阵,根据公式 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> A = ∑ i = 1 640 s i p i ⃗ q i ⃗ T A = \sum_{i=1}^{640} s_{i}\vec{p_{i}}\vec{q_{i}}^{T} </math>A=∑i=1640sipi qi T,它由640个子矩阵相加而成。现在,我们分别进行"截断"近似:

- 仅使用最大的前8个子矩阵进行重建。

- 仅使用最大的前30个子矩阵进行重建。

- 仅使用最大的前80个子矩阵进行重建。

然后,我们观察这些近似结果与原始图像的对比:

从上图可以清晰地看到:

- 第一张图是原始图像,由全部640个成分组成。

- 第二张图仅保留了最核心的8个成分,已经能勾勒出人物的基本轮廓和主要特征,尽管细节模糊且存在块状伪影。

- 第三张图在轮廓的基础上,恢复了更多的细节和纹理,图像质量显著提升。

- 第四张图已经能够非常出色地还原原图像,绝大多数细节都得以保留。

这个实验生动地展示了SVD降维的威力:我们仅仅使用了前80个最重要的"特征层"(占总数的12.5%),就实现了对原始数据高达99%以上的视觉保真度。 而剩下的560个子矩阵,其对应的奇异值/权重已经变得非常小,它们所包含的视觉信息大多是极其细微的细节、平滑区域的渐变噪声,或者是人眼不敏感的极高频成分 。舍弃它们可以极大地节省"带宽"或"存储空间"。

如果你已经理解了前面的内容,那么真正的PCA主成分分析对你来说已经触手可及了。

现在假设我们有一个数据集,包含 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> m m </math>m 个样本,每个样本有 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> n n </math>n 个特征,可以将其表示为一个形状为 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> ( m , n ) (m,n) </math>(m,n) 的矩阵 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> A A </math>A。在进行 PCA 之前,我们通常需要对数据进行标准化处理(这是关键步骤,确保不同量纲的特征具有可比性)。

我们知道对于任意一个矩阵 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> A A </math>A(形状为 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> m × n m \times n </math>m×n),都能分解成三个矩阵的乘积 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> A = U S V T A=USV^{T} </math>A=USVT。在我们对矩阵 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> A A </math>A进行分解后,我们得到了如下矩阵:

- <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> U U </math>U是一个 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> m × m m \times m </math>m×m的正交矩阵

- <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> V T V^{T} </math>VT是一个 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> n × n n \times n </math>n×n的正交矩阵

- <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> S S </math>S是一个 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> m × n m \times n </math>m×n的对角矩阵

现在就看你要保留几个奇异值及其对应的子矩阵了,假设你只想保留最大的3个奇异值,那么就要对 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> U , S , V T U,S,V^{T} </math>U,S,VT进行截断处理;截断后的矩阵如下:

- <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> U ^ \hat{U} </math>U^:取 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> U U </math>U 的前 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> 3 3 </math>3 列,形状为 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> m × 3 m \times 3 </math>m×3

- <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> S ^ \hat{S} </math>S^:取 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> S S </math>S 的前 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> 3 3 </math>3 个奇异值构成的对角矩阵,形状为 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> 3 × 3 3 \times 3 </math>3×3

- <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> V ^ T \hat{V}^T </math>V^T:取 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> V T V^T </math>VT 的前 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> 3 3 </math>3 行,形状为 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> 3 × n 3 \times n </math>3×n

那么降维后的矩阵 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> A ′ = A ⋅ V ^ A' = A \cdot \hat{V} </math>A′=A⋅V^, <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> A ′ A' </math>A′的形状为 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> ( m , 3 ) (m,3) </math>(m,3);其中 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> V ^ \hat{V} </math>V^ 是 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> V ^ T \hat{V}^T </math>V^T 的转置

注意,对于等式 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> A = U S V T A=USV^{T} </math>A=USVT,在等式两边同乘一个 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> V V </math>V,得到 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> A V = U S V T V AV=USV^{T}V </math>AV=USVTV;因为 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> V V </math>V是正交矩阵,所以 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> V V T = E V V^T = E </math>VVT=E,原式就可以写成 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> A V = U S AV=US </math>AV=US

所以降维后的矩阵也可以由这个式子得到: <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> A ′ = U ^ ⋅ S ^ A' = \hat{U} \cdot \hat{S} </math>A′=U^⋅S^;两种方式是等价的。

矩阵 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> A ′ A' </math>A′即为我们通过 PCA 得到降维后的数据表示。这就是PCA主成分分析的数学流程了;到这里就结束了,我们的目标就是得到 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> A ′ A' </math>A′。我知道你看到这里肯定会很困惑,为什么仅仅通过这样的矩阵乘法就能实现降维?的确,数学是非常有趣的,仅靠白纸黑字和静态的图片可能很难领会到PCA的精髓,PCA需要从几何的角度来理解,这需要你有比较强的线性代数几何基础,如果你看不懂下面的我对PCA的解释,非常推荐看看3Blue1Brown的可视化线性代数教程和可视化PCA教程。

任何两个矩阵相乘,在几何上都可以看作是对空间施加了一次变换------包括拉伸、旋转等操作。具体来说,若矩阵 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> A A </math>A 与矩阵 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> B B </math>B 相乘得到 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> A ⋅ B A \cdot B </math>A⋅B,则相当于将矩阵 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> A A </math>A 所表示的向量按行(或以行为坐标的向量组)进行 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> B B </math>B 所定义的线性变换;反过来看,也可以理解为将矩阵 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> B B </math>B 所表示的向量按列(或以列为坐标的向量组)进行 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> A A </math>A 所定义的线性变换。

特别地,当变换矩阵为对角矩阵 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> S S </math>S 时, <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> A ⋅ S A \cdot S </math>A⋅S 意味着对 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> A A </math>A 的每一行向量,在由 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> S S </math>S 确定的各个正交轴方向上进行独立的缩放(即纯拉伸,无旋转)。此时, <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> S S </math>S 对角线上的数值就代表对应坐标轴方向上的拉伸因子。而当变换矩阵为正交矩阵 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> U U </math>U 时, <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> A ⋅ U A \cdot U </math>A⋅U 则 表示对 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> A A </math>A 的行向量进行一种"刚性"旋转变换,不改变向量的长度与彼此间的正交性,因此是保范数且保内积的变换。

基于这样的几何视角,我们可以理解:任何一个矩阵 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> A A </math>A 都可以通过单位矩阵 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> E E </math>E 经过一系列变换得到。具体来说,存在正交矩阵 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> U U </math>U与 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> V T V^T </math>VT,以及对角矩阵 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> S S </math>S,使得:

<math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML" display="block"> E ⋅ U ⋅ S ⋅ V T = A E \cdot U \cdot S \cdot V^T = A </math>E⋅U⋅S⋅VT=A这实际上是奇异值分解的几何表达:从单位矩阵 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> E E </math>E 出发,先经过 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> U U </math>U 进行旋转,再经过 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> S S </math>S 在各正交方向上做不同程度的拉伸,最后通过 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> V T V^T </math>VT 再做一次旋转,最终得到矩阵 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> A A </math>A。其中, <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> S S </math>S 的对角元素称为奇异值,它们的大小反映了对应方向上的拉伸强度。奇异值越大,说明该方向上的信息"强度"越高,对数据整体结构的贡献也越大。

值得注意的是,在 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> E ⋅ U ⋅ S E \cdot U \cdot S </math>E⋅U⋅S 这一步,矩阵的"形态"------即数据在各主要方向上的分布强度------实际上已经确定;最后的 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> V T V^T </math>VT 变换只是对整个结构做一次整体旋转,并不改变数据的内部相对关系与分布特性。因此,我们完全可以用 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> U ⋅ S U \cdot S </math>U⋅S 来捕捉 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> A A </math>A 的核心结构信息。这也意味着,如果我们希望降低数据的维度,可以保留奇异值较大的方向,而舍弃那些奇异值很小的方向,因为它们所包含的信息量很有限,对整体结构的贡献较小。

于是,降维后的近似矩阵可表示为:

<math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML" display="block"> A ′ = U ^ ⋅ S ^ A' = \hat{U} \cdot \hat{S} </math>A′=U^⋅S^

接下来,我们介绍如何在实际应用中高效地对大规模矩阵进行降维操作。这里我们借助 Python 的 sklearn 库来实现。不需要担心你不熟悉这个库,在学习这些强大的工具库(如 SciPy、scikit-learn、Pytorch)时,一个高效的策略是 "按需所学,而非系统通读" 。试图一开始就系统性地掌握一个庞大库的所有内容,很容易陷入大量专业术语的泥潭。更好的方式是,在具体项目中遇到什么需求,再去深入学习该库对应的模块。这能让你始终保持目标清晰,理解也更为深刻。

下面我们就来学习如何使用 sklearn 中提供的 PCA 类,它内部基于高效且稳定的 SVD 实现,只需几行代码即可完成降维。

sklearn库的安装方法为:

bash

pip install scikit-learn使用示例:

python

import numpy as np

from sklearn.decomposition import TruncatedSVD

# 示例数据

A = np.array([[3, 4, 3],

[5, 1, 6],

[7, 2, 9],

[8, 3, 7]])

# 初始化截断 SVD,保留前 2 个最大的主成分/奇异值

svd = TruncatedSVD(n_components=2)

# 进行数据降维

# 计算出来的result_A就是A',因为只保留了两个最大的主成分,所以A'矩阵只有两列

result_A = svd.fit_transform(A)

s = svd.singular_values_ # 奇异值数组

V_t = svd.components_ # 因为只保留了两个最大的主成分,所以V_t矩阵只有两行

# 获取分解结果

print("奇异值s:", s)

print("V_t:", V_t)

print("A'",result_A)

# ===输出===

奇异值s:

[18.43513181 3.20662265]

V_t:

[[ 0.65528575 0.24759647 0.71365018]

[ 0.02053089 0.93856832 -0.34448222]]

A':

[[ 5.09719365 2.78241927]

[ 7.80592628 -1.02567055]

[11.50504478 -1.07948712]

[10.98062664 0.56857653]]要想通过 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> A ′ A' </math>A′重建原来的 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> A A </math>A也很简单,因为 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> A ′ = A ⋅ V ^ A' = A \cdot \hat{V} </math>A′=A⋅V^,所以 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> A = A ′ ⋅ V ^ T A = A' \cdot \hat{V}^{T} </math>A=A′⋅V^T;注意,因为 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> A ′ A' </math>A′是已经降维后的矩阵了,降维过程中丢弃了部分信息,我们无法完全精确地还原原始数据,转换回的新的 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> A A </math>A后也不再是原来的 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> A A </math>A了,它肯定与原始 <math xmlns="http://www.w3.org/1998/Math/MathML"> A A </math>A接近,但存在些许差异,这就要看你保留了多少奇异值了。

python

new_A = result_A @ V_t

print(new_A)

# ===输出===

[[3.39724391, 3.8735377 , 2.67911918],

[5.09405433, 0.97005788, 5.92402595],

[7.51692906, 1.83543602, 8.58244137],

[7.20712154, 3.25241226, 7.64046165]]以上就是PCA算法的全部内容。可以看到,PCA的数学原理较为直观,实现也相对容易;但正因如此,它也存在明显的局限性。PCA只能捕捉数据中的线性结构,对于非线性复杂关系的降维效果往往不够理想。此外,PCA对异常值较为敏感,极端值可能会显著影响主成分的方向,从而降低降维结果的质量。

尽管如此,PCA依然是目前最常用和基础的降维方法之一。在实际应用中,很多降维流程会先使用PCA进行初步处理,消除部分噪声与冗余,再结合其他非线性降维方法进一步提取数据结构。

二. UMAP算法

UMAP是一种近年来广受关注的非线性降维算法。与PCA相比,UMAP能够更有效地捕捉数据中复杂的非线性结构,因此在许多实际任务中表现更为强大。

UMAP的理论基础建立在坚实的现代数学框架之上,主要涉及黎曼几何与代数拓扑。它通过构建高维空间中的数据拓扑结构,并尝试在低维空间中保持该结构的本质特征。简单来说,UMAP 的核心思想是在降维过程中尽量保持数据的局部结构------就好像将高维空间中的几何形状"平滑地展开"到低维空间中,形成一张保持相对结构的"解剖图"。

相较于其他非线性降维方法(如 t-SNE),UMAP 的优势非常明显,比如计算效率很高,内存消耗更小,可以处理百万级别的数据等。

尽管UMAP与PCA的最终目标一致------减少数据维度、去除冗余信息,但二者处理数据内在结构的方式有本质不同。下面我们将重点介绍如何使用UMAP工具包进行降维,而不深入其数学细节。

首先需要安装UMAP库

bash

pip install umap-learn为了直观展示UMAP的降维效果,我们以经典的鸢尾花(Iris)数据集为例,演示完整的降维流程。这是一个多分类数据集,包含3个类别(三种鸢尾花品种),每个类别50个样本,共150个样本。每个样本有4个特征:花萼长度、花萼宽度、花瓣长度和花瓣宽度。

鸢尾花(Iris)数据集是sklearn库自带的,只要你之前安装过sklearn库就已经内置了这个数据集了。

python

import numpy as np

from sklearn.datasets import load_iris # 引入鸢尾花数据集

# 加载鸢尾花数据集

iris = load_iris()

A = iris.data # 获取特征矩阵,类型为numpy数组

labels = iris.target # 标签向量,0/1/2分别对应三种鸢尾花

print(A.shape) # 获取A的形状

print(A[0:10]) # 查看前10个数据

# ===输出===

(150, 4)

[[5.1 3.5 1.4 0.2]

[4.9 3. 1.4 0.2]

[4.7 3.2 1.3 0.2]

[4.6 3.1 1.5 0.2]

[5. 3.6 1.4 0.2]

[5.4 3.9 1.7 0.4]

[4.6 3.4 1.4 0.3]

[5. 3.4 1.5 0.2]

[4.4 2.9 1.4 0.2]

[4.9 3.1 1.5 0.1]]在获取到样本矩阵后,要对其进行标准化处理(这一步非常关键!PCA中在降维前也是要先进行标准化处理!),之后才能进行降维操作。

python

# 进行标准化处理

from sklearn.preprocessing import StandardScaler

scaler = StandardScaler()

scaled_A = scaler.fit_transform(A) # 对A进行标准化

print(scaled_A[0:10]) # 查看前10个数据

# === 输出 ===

[[-0.90068117 1.01900435 -1.34022653 -1.3154443 ]

[-1.14301691 -0.13197948 -1.34022653 -1.3154443 ]

[-1.38535265 0.32841405 -1.39706395 -1.3154443 ]

[-1.50652052 0.09821729 -1.2833891 -1.3154443 ]

[-1.02184904 1.24920112 -1.34022653 -1.3154443 ]

[-0.53717756 1.93979142 -1.16971425 -1.05217993]

[-1.50652052 0.78880759 -1.34022653 -1.18381211]

[-1.02184904 0.78880759 -1.2833891 -1.3154443 ]

[-1.74885626 -0.36217625 -1.34022653 -1.3154443 ]

[-1.14301691 0.09821729 -1.2833891 -1.44707648]]接下来进行umap降维:

python

import umap

# 初始化 UMAP 模型,设定目标维度为2,固定随机种子以保证可重复性

reducer = umap.UMAP(n_components=2, random_state=42)

embedding_A = reducer.fit_transform(scaled_A) # 进行UMAP数据降维

print(embedding_A.shape) # 查看降维后的数据形状

print(embedding_A[0:10]) # 查看降维后的前10个样本

# === 输出 ===

(150, 2)

[[13.515001 4.9760547]

[11.787091 3.2109737]

[11.698444 3.7325902]

[11.408422 3.5530434]

[13.728321 5.26629 ]

[14.782503 5.270304 ]

[12.758788 4.6392527]

[13.191469 4.637623 ]

[11.2218685 3.2424262]

[11.846259 3.354508 ]]umap.UMAP()函数的常用参数如下:

| 参数 | 作用 | 推荐范围 | 影响 |

|---|---|---|---|

n_neighbors |

控制局部结构的粒度 | 5~50(默认15) | ↗️ 值越大保留全局结构,↘️ 值越小保留局部细节 |

min_dist |

控制点的聚集程度 | 0.001~0.5(默认0.1) | ↗️ 值越大点越分散,↘️ 值越小聚类越紧密 |

n_components |

降维后的维度 | 2或3(用于可视化) | 一般选2维绘图,3维可交互 |

metric |

距离度量方法 | 'euclidean'(默认)、'cosine'、'manhattan' | 根据数据特性选择,例如文本用余弦距离 |

n_jobs |

并行计算使用的CPU核心数 | 根据自己电脑CPU核心数适当配置 | 加速计算 |

random_state |

随机种子 | 任意整数 | 固定后可保证每次运行结果一致。 |

注意:一般情况下umap要保留参数random_state,这样才能保证每次运行结果一致。使得结果可重现。缺点就是它只能在一个CPU核心上运行。若是reducer = umap.UMAP(n_components=2, n_jobs=-1) # -1 表示使用所有CPU核心,就是并行计算,运算速度会大大提升,缺点就是每次降维后的结果可能不同,这种只适合数据可视化的时候使用。

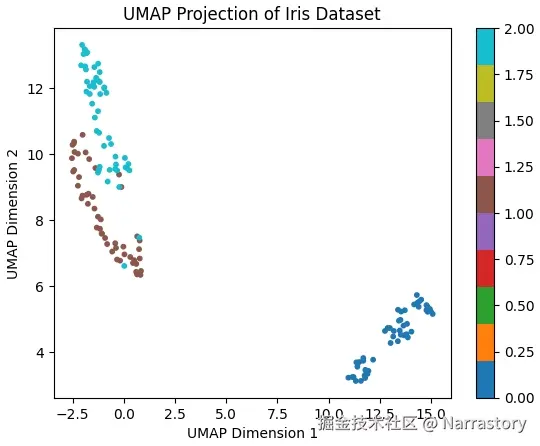

将数据降至二维后,我们可以将这些点绘制在平面直角坐标系中,直观查看降维效果,并用颜色区分不同类别。

python

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt # 引入matplotlib库绘制图表

# 数据可视化(使用散点图)

y = data.target # 获取每个样本的标签

plt.scatter(embedding[:, 0], embedding[:, 1], c=y, cmap="tab10", s=10)

plt.title("UMAP Projection of Iris Dataset")

plt.xlabel("UMAP Dimension 1")

plt.ylabel("UMAP Dimension 2")

plt.colorbar()

plt.show()从图中可以看出,降维后的二维数据依然保持了原始数据中三个类别的分离结构,同类样本聚集在一起,不同类之间边界清晰。这说明 UMAP 在降维过程中有效保留了数据的类别信息。

如果你已经用umap降维后的训练集训练了一个模型,那么未来进行推理的时候,新数据如何进行预处理呢?对训练集的数据是如何进行预处理的,那么对新数据就是一样的预处理。

python

newData2Predicted = np.array([[4,3,1,0.3]]) # 一个新数据,需要输入到模型中进行运算

# 先将其标准化,再转换为低维,再送到模型中去运算

# 注意不能再创建新的scaler和reducer,必须是之前在处理训练集时定义的scaler和reducer才行。

lowDemensionVersion = reducer.transform(scaler.transform(newData2Predicted))

# 降维后的新数据

print(lowDemensionVersion)

# === 输出 ===

[[11.103776 , 3.8664804]]更常用的方法是本地化保存这两个预处理函数scaler和reducer

python

import joblib

# 本地化数据预处理模型,将其保存为本地文件

joblib.dump(scaler, 'scaler.pkl')

joblib.dump(reducer, "reducer.pkl")

python

newData2Predicted = np.array([[4, 3, 1, 0.3]]) # 一个新数据

# 需要使用的时候再通过加载预处理模型来对其进行预处理

savedScaler = joblib.load('./scaler.pkl')

savedReducer = joblib.load('./reducer.pkl')

newLowDemensionVersion = savedReducer.transform(savedScaler.transform(newData2Predicted))

print(newLowDemensionVersion)

# === 输出 ===

[[11.103776 , 3.8664804]]