上篇博客我们学习了系统IO接口,几乎每一个接口都会使用到fd,那么fd到底是什么呢,本篇博客就会带你了解文件描述符--fd

1.⽂件描述符fd定义

通过对open函数的学习,我们知道了⽂件描述符就是⼀个⼩整数

2.fd :0 & 1 & 2

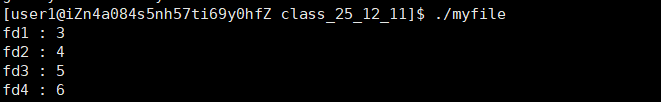

我们看看创建多个文件,每个文件的fd是多少

myfile.c代码:

cpp

#include <stdio.h>

#include <sys/types.h>

#include <sys/stat.h>

#include <fcntl.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <string.h>

int main()

{

umask(0);

int fd1 = open("log1.txt", O_CREAT | O_WRONLY | O_TRUNC, 0666);

int fd2 = open("log2.txt", O_CREAT | O_WRONLY | O_TRUNC, 0666);

int fd3 = open("log3.txt", O_CREAT | O_WRONLY | O_TRUNC, 0666);

int fd4 = open("log4.txt", O_CREAT | O_WRONLY | O_TRUNC, 0666);

if (fd1 < 0)

{

perror("fd1 open");

return 1;

}

if (fd2 < 0)

{

perror("fd2 open");

return 1;

}

if (fd3 < 0)

{

perror("fd3 open");

return 1;

}

if (fd4 < 0)

{

perror("fd4 open");

return 1;

}

printf ("fd1 : %d\n", fd1);

printf ("fd2 : %d\n", fd2);

printf ("fd3 : %d\n", fd3);

printf ("fd4 : %d\n", fd4);

close(fd1);

close(fd2);

close(fd3);

close(fd4);

return 0;

}运行结果如下:

他们使一个一个递增的,并且最开始是3,那么0,1,2去哪儿呢??

Linux进程默认情况下会有3个缺省打开的⽂件描述符,分别是标准输⼊0, 标准输出1, 标准错

误2

0,1,2对应的物理设备⼀般是:键盘,显⽰器,显⽰器

可是我们也学过c语言的标准输入,标准输出,标准错误

同样的c++也有对应的cin,cout,cerr

这些与我们现在学习的系统级别的0,1,2有什么联系呢??

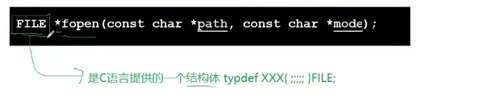

如果我们仔细观察fopen的函数,其实就会发现他调用的是FILE,但是我们从来没有真正认识FILE,其实他就是一个c语言提供的一个struct结构体

而且我们从上一篇博客知道,每个语言层的接口背后一定会调用系统层的IO函数,而系统层只认fd ,也就是文件描述符,所以我们可以百分百确定,在FILE这个结构体内,一定会有一个变量,记录着fd!!!

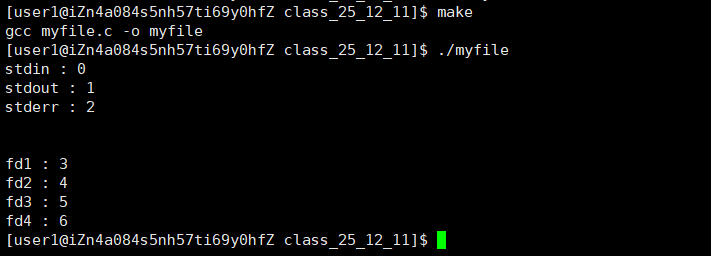

现在我们来验证一下我们的猜测,将c语言里面的std_fd打印出来

myfile.c代码:

cpp

#include <stdio.h>

#include <sys/types.h>

#include <sys/stat.h>

#include <fcntl.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <string.h>

int main()

{

printf("stdin : %d\n", stdin->_fileno);

printf("stdout : %d\n", stdout->_fileno);

printf("stderr : %d\n", stderr->_fileno);

printf("\n\n");

umask(0);

int fd1 = open("log1.txt", O_CREAT | O_WRONLY | O_TRUNC, 0666);

int fd2 = open("log2.txt", O_CREAT | O_WRONLY | O_TRUNC, 0666);

int fd3 = open("log3.txt", O_CREAT | O_WRONLY | O_TRUNC, 0666);

int fd4 = open("log4.txt", O_CREAT | O_WRONLY | O_TRUNC, 0666);

if (fd1 < 0)

{

perror("fd1 open");

return 1;

}

if (fd2 < 0)

{

perror("fd2 open");

return 1;

}

if (fd3 < 0)

{

perror("fd3 open");

return 1;

}

if (fd4 < 0)

{

perror("fd4 open");

return 1;

}

printf ("fd1 : %d\n", fd1);

printf ("fd2 : %d\n", fd2);

printf ("fd3 : %d\n", fd3);

printf ("fd4 : %d\n", fd4);

close(fd1);

close(fd2);

close(fd3);

close(fd4);

return 0;

}结论正确!!

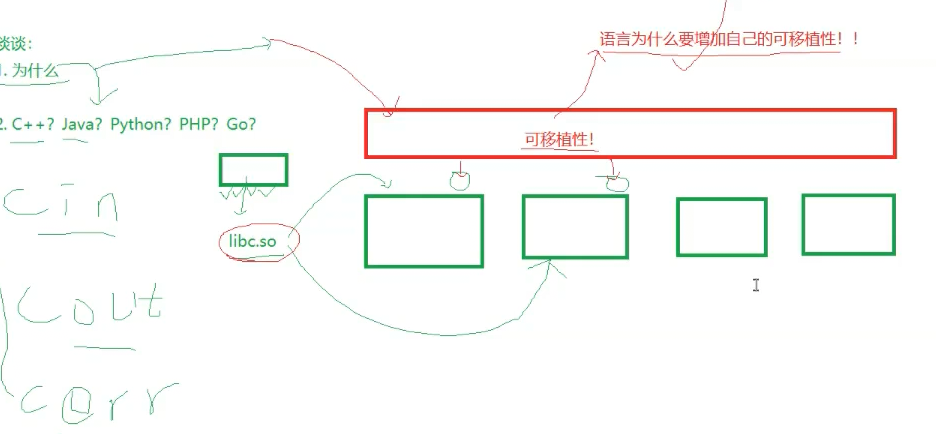

3.为什么要底层封装fd

我们一直用c语言做例子,其实c++,java等等等语言底层调用文件接口都会存在fd封装,可是为什么要这么做呢

-

屏蔽系统差异,实现跨平台(可移植性) 不同系统的底层 IO 接口完全不同:Linux 用

fd(int)+open/read,Windows 用句柄(HANDLE)+CreateFile/ReadFile。封装后会提供统一的抽象接口 (如 C 的FILE*、Java 的FileInputStream),开发者不用写系统判断代码,一行代码跨 Linux/Windows/macOS -

提升易用性,降低开发成本 裸 fd 是原始系统调用,需要手动处理返回值、缓冲区、字节数,代码繁琐易出错;封装后提供人性化功能(比如 C 的

FILE*有用户态缓冲、fprintf格式化读写,Java 的流支持按行读取),开发者只需关注 "怎么读写",不用关心底层 fd 操作 -

增强安全性,避免资源问题 裸 fd 容易出现泄漏(忘关 fd)、非法操作(用已关闭的 fd 读写)、缓冲区越界;封装后会自动管理资源(如 C++ 的 RAII 自动关闭 fd、Java 的

try-with-resources自动释放),还会强制处理错误,减少风险 -

提供高级抽象功能裸 fd 只能处理字节流,封装后支持按行、按对象、按字符编码(如 UTF-8)读写,这些高级功能是开发中刚需,不用开发者自己造轮子

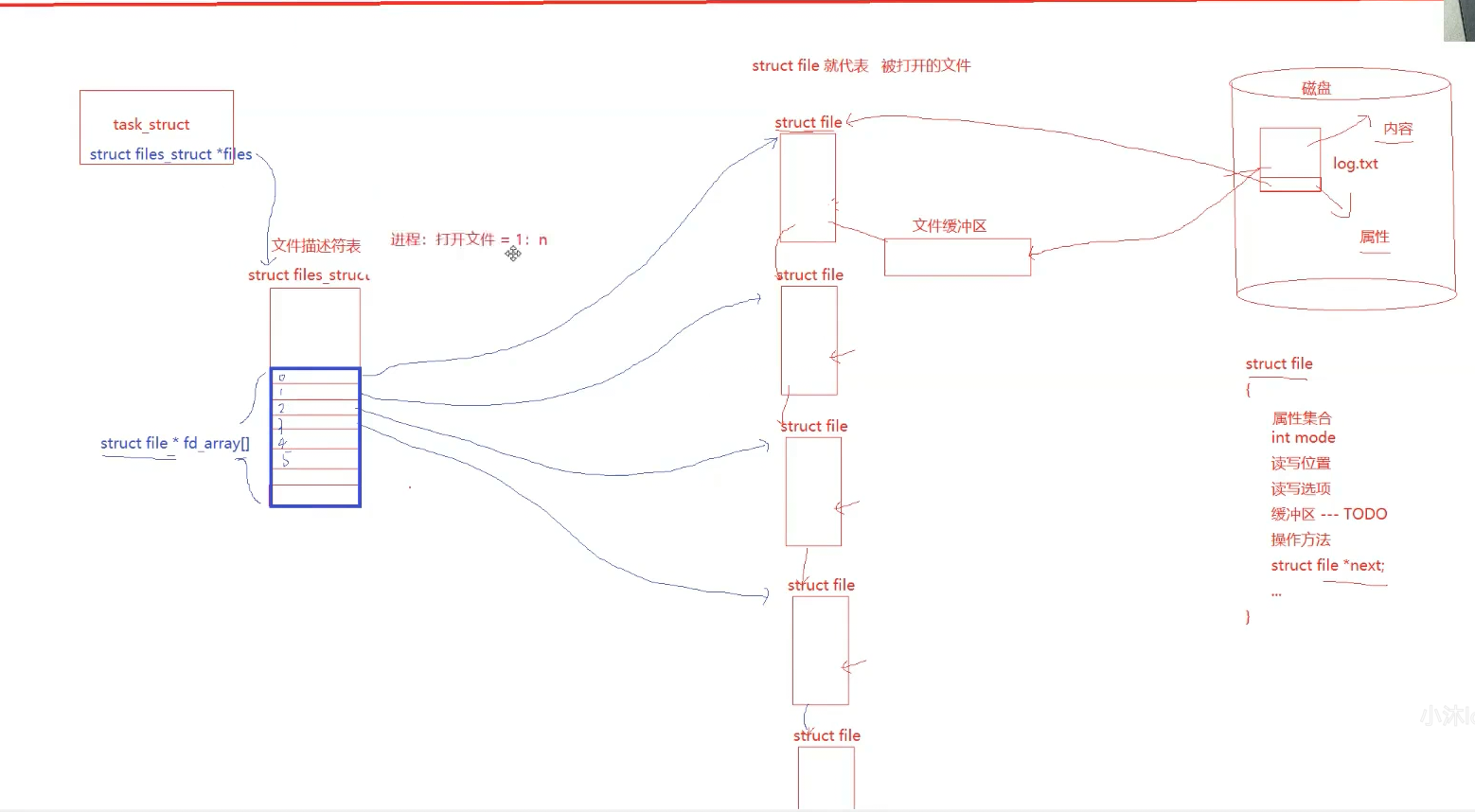

4.深入认识文件描述符fd

想一想我们学习的时候,什么数据结构会用到0,1,2,3,4...来查找对应内容

答案是数组!

下面我将为你解答一下,文件从磁盘到内存,以及进程如何管理文件的全过程

如上图,我们先要知道一个进程可能会管理多个文件,同时这些文件有的可能要被打开,有的正在使用,有的打算关闭,而且系统里面存在多个进程,最后可能会有100个进程10000个文件,那么这些进程该怎么管理这些文件呢,我们类比一下就会想到进程调度,也是1:n的管理关系,采用的是链表链接struct的形式管理的

所以我们也可以这样做

系统先读取磁盘文件到一个结构体struct_file里面,这个结构体保存着文件的属性集合,mode,读写位置等等等,其中还有一个缓冲区,这个缓冲区存放在文件的内容,文件的属性交给了其他变量

进程会打开很多个文件,于是这些被打开的文件就用链表连接起来,形成一个struct file*指针

同时进程有一个struct files_struct表(文件描述符表),里面有一个数组,是file*类型的指证数组,所以0,1,2,3...下标就对应数组里面的file*,而file*又表示打开的文件,与最开始形成闭环,完美阐释了什么叫做先描述再组织!

所以总的来说

⽂件描述符就是从0开始的⼩整数。当我们打开⽂件时,操作系统在内存中要创建相应的 数据结构来描述⽬标⽂件。于是就有了file结构体。表⽰⼀个已经打开的⽂件对象。⽽进程执⾏open系

统调⽤,所以必须让进程和⽂件关联起来。每个进程都有⼀个指针*files, 指向⼀张表files_struct,该表最重要的部分就是包含⼀个指针数组,每个元素都是⼀个指向打开⽂件的指针!所以,本质上,⽂件 描述符就是该数组的下标。所以,只要拿着⽂件描述符,就可以找到对应的⽂件

下面是linux底层源码

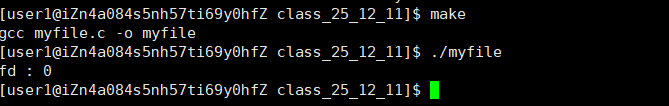

5.⽂件描述符的分配规则

我们知道文件描述符会从3开始,一直往后,那么假如我们将0关掉,然后再打开一个文件,fd又会是多少呢,是0,还是3?

下面我们来做实验:

myfile.c:

cpp

#include <stdio.h>

#include <sys/types.h>

#include <sys/stat.h>

#include <fcntl.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <string.h>

int main()

{

//printf("stdin : %d\n", stdin->_fileno);

//printf("stdout : %d\n", stdout->_fileno);

//printf("stderr : %d\n", stderr->_fileno);

//printf("\n\n");

close(0);

umask(0);

int fd = open("fd.txt", O_CREAT | O_WRONLY | O_TRUNC, 0666);

if (fd < 0)

{

perror("fd open");

return 1;

}

printf("fd : %d\n", fd);

close(fd);

//int fd1 = open("log1.txt", O_CREAT | O_WRONLY | O_TRUNC, 0666);

//int fd2 = open("log2.txt", O_CREAT | O_WRONLY | O_TRUNC, 0666);

//int fd3 = open("log3.txt", O_CREAT | O_WRONLY | O_TRUNC, 0666);

//int fd4 = open("log4.txt", O_CREAT | O_WRONLY | O_TRUNC, 0666);

//if (fd1 < 0)

//{

// perror("fd1 open");

// return 1;

//}

//if (fd2 < 0)

//{

// perror("fd2 open");

// return 1;

//}

//if (fd3 < 0)

//{

// perror("fd3 open");

// return 1;

//}

//if (fd4 < 0)

//{

// perror("fd4 open");

// return 1;

//}

//printf ("fd1 : %d\n", fd1);

//printf ("fd2 : %d\n", fd2);

//printf ("fd3 : %d\n", fd3);

//printf ("fd4 : %d\n", fd4);

//close(fd1);

//close(fd2);

//close(fd3);

//close(fd4);

return 0;

}运行结果是0,所以说明文件描述符分配规则就是从0开始,一直往后找空缺,有空缺就将返回对应下标,即fd

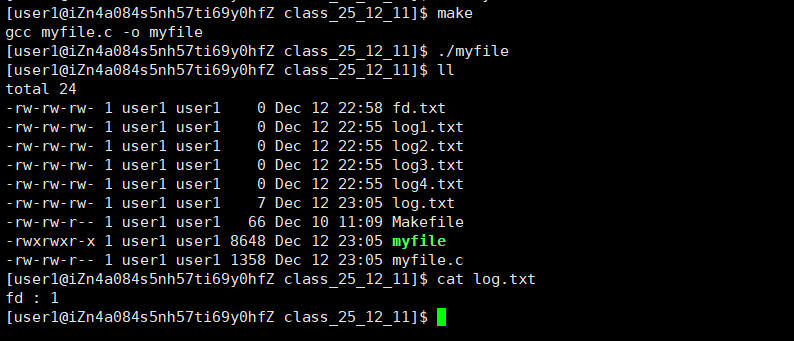

6.重定向

我们之前谈过很多重定向,但是重定向到底是什么,怎么实现的,我们没有了解,下面我们用一组代码来开始探索重定向操作

myfile.c:

cpp

#include <stdio.h>

#include <sys/types.h>

#include <sys/stat.h>

#include <fcntl.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <string.h>

int main()

{

//printf("stdin : %d\n", stdin->_fileno);

//printf("stdout : %d\n", stdout->_fileno);

//printf("stderr : %d\n", stderr->_fileno);

//printf("\n\n");

close(1);

umask(0);

int fd = open("log.txt", O_CREAT | O_WRONLY | O_TRUNC, 0666);

if (fd < 0)

{

perror("fd open");

return 1;

}

printf("fd : %d\n", fd);

//close(fd);

//int fd1 = open("log1.txt", O_CREAT | O_WRONLY | O_TRUNC, 0666);

//int fd2 = open("log2.txt", O_CREAT | O_WRONLY | O_TRUNC, 0666);

//int fd3 = open("log3.txt", O_CREAT | O_WRONLY | O_TRUNC, 0666);

//int fd4 = open("log4.txt", O_CREAT | O_WRONLY | O_TRUNC, 0666);

//if (fd1 < 0)

//{

// perror("fd1 open");

// return 1;

//}

//if (fd2 < 0)

//{

// perror("fd2 open");

// return 1;

//}

//if (fd3 < 0)

//{

// perror("fd3 open");

// return 1;

//}

//if (fd4 < 0)

//{

// perror("fd4 open");

// return 1;

//}

//printf ("fd1 : %d\n", fd1);

//printf ("fd2 : %d\n", fd2);

//printf ("fd3 : %d\n", fd3);

//printf ("fd4 : %d\n", fd4);

//close(fd1);

//close(fd2);

//close(fd3);

//close(fd4);

return 0;

}

咦?为什么没有在显示屏输出fd : 1,而是将这句话打印到了log.txt文件了呢??

此时,我们发现,本来应该输出到显⽰器上的内容,输出到了⽂件 myfile 当中,其中,fd=1。这

种现象叫做输出重定向。常⻅的重定向有: > , >> , <,<<

那这个现象是怎么发生的呢?

我们首先关闭了1,那么我们创建的log.txt描述符就找到了这个空缺,所以fd就为1,而printf是c语言提供的输出,底层默认输出到stdout,而stdout是语言层封装的,底层只认识fd=1的文件,所以此时stdout就被替换为了log.txt,即向log.txt输出fd : 1,所以会出现这个情况,这就是重定向操作

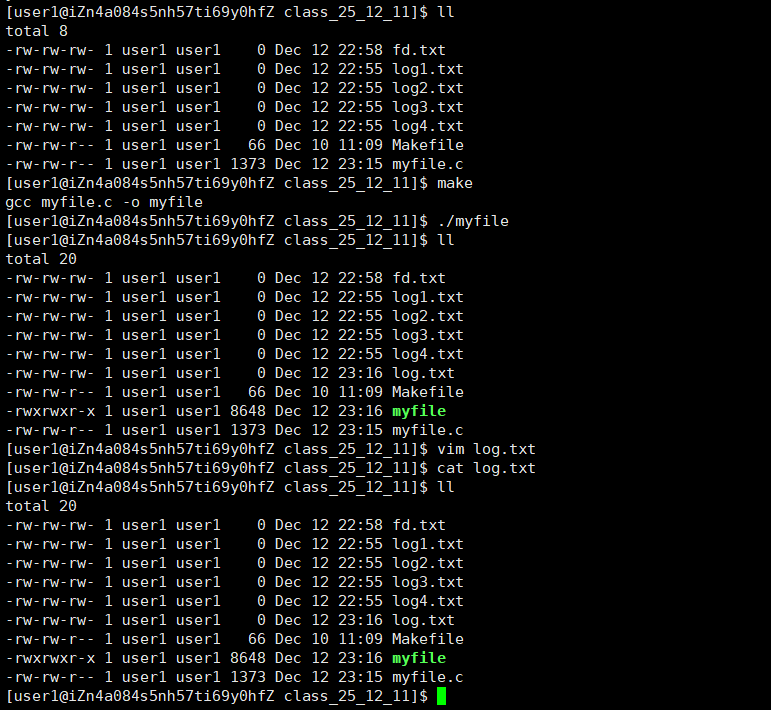

如果你仔细观察myfile.c代码,就会发现我们没有close(fd),那如果我们将close(fd)加上会发什么呢?(请每次./myfile前将log.txt删掉,不然无法创建新的文件来进行实验)

myfile.c:

cpp

#include <stdio.h>

#include <sys/types.h>

#include <sys/stat.h>

#include <fcntl.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <string.h>

int main()

{

//printf("stdin : %d\n", stdin->_fileno);

//printf("stdout : %d\n", stdout->_fileno);

//printf("stderr : %d\n", stderr->_fileno);

//printf("\n\n");

close(1);

umask(0);

int fd = open("log.txt", O_CREAT | O_WRONLY | O_TRUNC, 0666);

if (fd < 0)

{

perror("fd open");

return 1;

}

printf("fd : %d\n", fd);

close(fd);

//close(fd);

//int fd1 = open("log1.txt", O_CREAT | O_WRONLY | O_TRUNC, 0666);

//int fd2 = open("log2.txt", O_CREAT | O_WRONLY | O_TRUNC, 0666);

//int fd3 = open("log3.txt", O_CREAT | O_WRONLY | O_TRUNC, 0666);

//int fd4 = open("log4.txt", O_CREAT | O_WRONLY | O_TRUNC, 0666);

//if (fd1 < 0)

//{

// perror("fd1 open");

// return 1;

//}

//if (fd2 < 0)

//{

// perror("fd2 open");

// return 1;

//}

//if (fd3 < 0)

//{

// perror("fd3 open");

// return 1;

//}

//if (fd4 < 0)

//{

// perror("fd4 open");

// return 1;

//}

//printf ("fd1 : %d\n", fd1);

//printf ("fd2 : %d\n", fd2);

//printf ("fd3 : %d\n", fd3);

//printf ("fd4 : %d\n", fd4);

//close(fd1);

//close(fd2);

//close(fd3);

//close(fd4);

return 0;

}东西去哪儿呢,为什么显示屏没有,log.txt也没有内容??

要解决这个问题,需要我们学习缓冲区才可以理解,现在不做讲解!

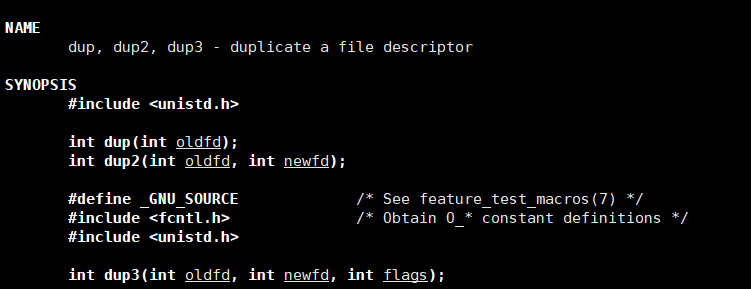

但是我们要更改一次文件描述符,需要先close要改到的位置,然后再open,非常麻烦,有没有简单点的方法呢??答案是有的,那就是使用函数dup2();

下面是man dup2的定义

怎么使用呢,比如我们要把fd 指向 1,那么就是dup2(fd, 1),但是只是指针指向,并不会将fd与1交换值

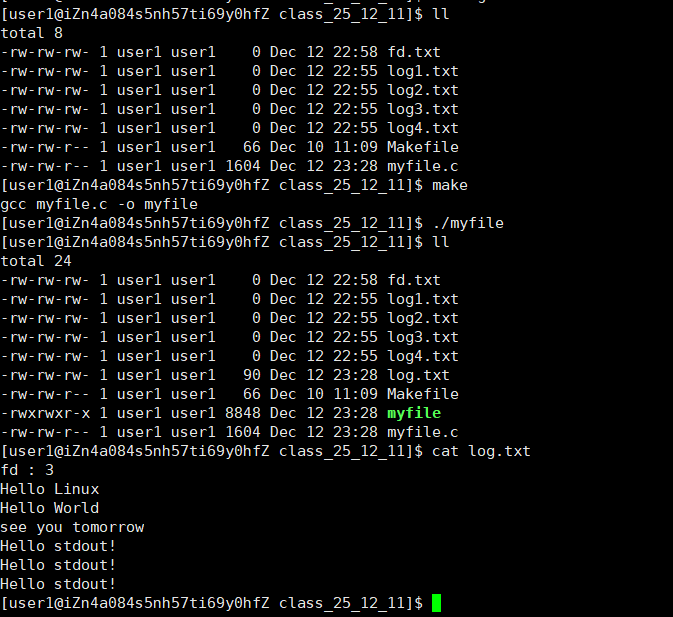

下面是myfile.c验证:

cpp

#include <stdio.h>

#include <sys/types.h>

#include <sys/stat.h>

#include <fcntl.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <string.h>

int main()

{

//printf("stdin : %d\n", stdin->_fileno);

//printf("stdout : %d\n", stdout->_fileno);

//printf("stderr : %d\n", stderr->_fileno);

//printf("\n\n");

//close(1);

umask(0);

int fd = open("log.txt", O_CREAT | O_WRONLY | O_TRUNC, 0666);

if (fd < 0)

{

perror("fd open");

return 1;

}

dup2(fd, 1);

close(fd);

printf("fd : %d\n", fd);

printf("Hello Linux\n");

printf("Hello World\n");

printf("see you tomorrow\n");

fprintf(stdout, "Hello stdout!\n");

fprintf(stdout, "Hello stdout!\n");

fprintf(stdout, "Hello stdout!\n");

//close(fd);

//int fd1 = open("log1.txt", O_CREAT | O_WRONLY | O_TRUNC, 0666);

//int fd2 = open("log2.txt", O_CREAT | O_WRONLY | O_TRUNC, 0666);

//int fd3 = open("log3.txt", O_CREAT | O_WRONLY | O_TRUNC, 0666);

//int fd4 = open("log4.txt", O_CREAT | O_WRONLY | O_TRUNC, 0666);

//if (fd1 < 0)

//{

// perror("fd1 open");

// return 1;

//}

//if (fd2 < 0)

//{

// perror("fd2 open");

// return 1;

//}

//if (fd3 < 0)

//{

// perror("fd3 open");

// return 1;

//}

//if (fd4 < 0)

//{

// perror("fd4 open");

// return 1;

//}

//printf ("fd1 : %d\n", fd1);

//printf ("fd2 : %d\n", fd2);

//printf ("fd3 : %d\n", fd3);

//printf ("fd4 : %d\n", fd4);

//close(fd1);

//close(fd2);

//close(fd3);

//close(fd4);

return 0;

}

符合预期~~

所以有了上面的知识,现在我们可以知道了

> 无非就是dup2(fd1, fd2)并且清空写入

>> 无非就是dup2(fd1, fd2) 并且添加写入

...

我们还可以完成类似cat的操作:

myfile.c:

cpp

#include <stdio.h>

#include <sys/types.h>

#include <sys/stat.h>

#include <fcntl.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <string.h>

int main(int argc, char* argv[])

{

if (argc != 2)

{

return 1;

}

int fd = open(argv[1], O_RDONLY);

if (fd < 0)

{

perror("fd open");

return 1;

}

dup2(fd, 0);

close(fd);

while (1)

{

char buffer[64];

int n = read(0, buffer, sizeof(buffer) - 1);

if (n > 0)

{

buffer[n] = '\0';

printf("%s", buffer);

}

else

{

break;

}

}

return 0;

}

//int main()

//{

// //printf("stdin : %d\n", stdin->_fileno);

// //printf("stdout : %d\n", stdout->_fileno);

// //printf("stderr : %d\n", stderr->_fileno);

// //printf("\n\n");

// //close(1);

// umask(0);

// int fd = open("log.txt", O_CREAT | O_WRONLY | O_TRUNC, 0666);

// if (fd < 0)

// {

// perror("fd open");

// return 1;

// }

// dup2(fd, 1);

// close(fd);

// printf("fd : %d\n", fd);

// printf("Hello Linux\n");

// printf("Hello World\n");

// printf("see you tomorrow\n");

// fprintf(stdout, "Hello stdout!\n");

// fprintf(stdout, "Hello stdout!\n");

// fprintf(stdout, "Hello stdout!\n");

// //close(fd);

// //int fd1 = open("log1.txt", O_CREAT | O_WRONLY | O_TRUNC, 0666);

// //int fd2 = open("log2.txt", O_CREAT | O_WRONLY | O_TRUNC, 0666);

// //int fd3 = open("log3.txt", O_CREAT | O_WRONLY | O_TRUNC, 0666);

// //int fd4 = open("log4.txt", O_CREAT | O_WRONLY | O_TRUNC, 0666);

// //if (fd1 < 0)

// //{

// // perror("fd1 open");

// // return 1;

// //}

// //if (fd2 < 0)

// //{

// // perror("fd2 open");

// // return 1;

// //}

// //if (fd3 < 0)

// //{

// // perror("fd3 open");

// // return 1;

// //}

// //if (fd4 < 0)

// //{

// // perror("fd4 open");

// // return 1;

// //}

// //printf ("fd1 : %d\n", fd1);

// //printf ("fd2 : %d\n", fd2);

// //printf ("fd3 : %d\n", fd3);

// //printf ("fd4 : %d\n", fd4);

// //close(fd1);

// //close(fd2);

// //close(fd3);

// //close(fd4);

// return 0;

//}

原本read(0)是从键盘 读取输入,重定向后,read(0)会从命令行参数指定的文件 中读取内容,相当于 Shell 中的<重定向(比如./a.out test.txt等价于./a.out < test.txt)