本篇博客我们将真正理解Linux下一切皆文件的概念与文件缓存区,并且编写一个简单的libc,话不多说,我们现在开始~~

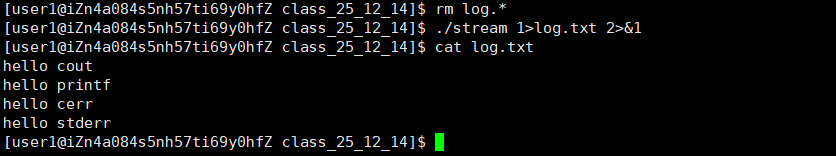

1.了解stderr,补充重定向

在这之前,我们将重新理解一下重定向以及err(标准错误)

cpp

#include <iostream>

#include <cstdio>

int main()

{

std::cout << "hello cout" << std::endl;

printf("hello printf\n");

std::cerr << "hello cerr" << std::endl;

fprintf(stderr, "hello stderr\n");

return 0;

}按照我们之前的理解,我们前两句将写入标准输出,后面两句将写到标准错误文件中

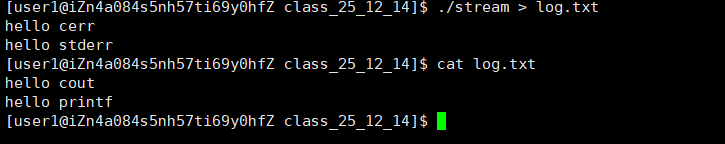

我们在加入重定向操作后,标准错误输出在显示屏上,而标准输出输出在log.txt中,为什么呢

因为我们>会打开第一个文件,也就是标准输出,而没有打开标准错误,那如果我们要输出标准输出,而将标准错误输出到log.txt中呢,此时我们就要再次理解>了,其实>并不是真正的写法,而是fd>...,fd是你要替换的文件描述符

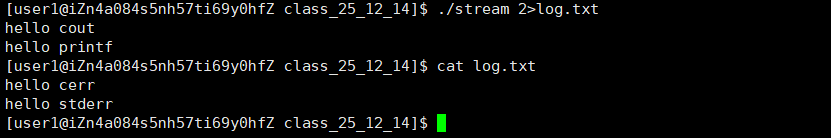

所以可以这样写:

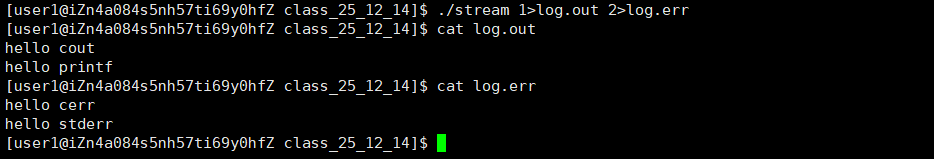

这里要挨着一起才行,那要是我们想要标准输出在一个文件,标准错误在一个文件呢

那么只需要使用下面代码就行:

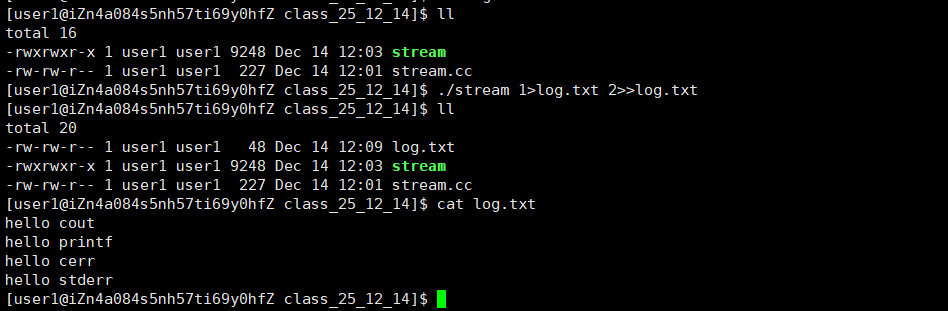

那要是我们想在一个文件输出这些内容呢,有两种写法:

写法一:

写法二:

为什么要有标准错误呢?下图是原因:

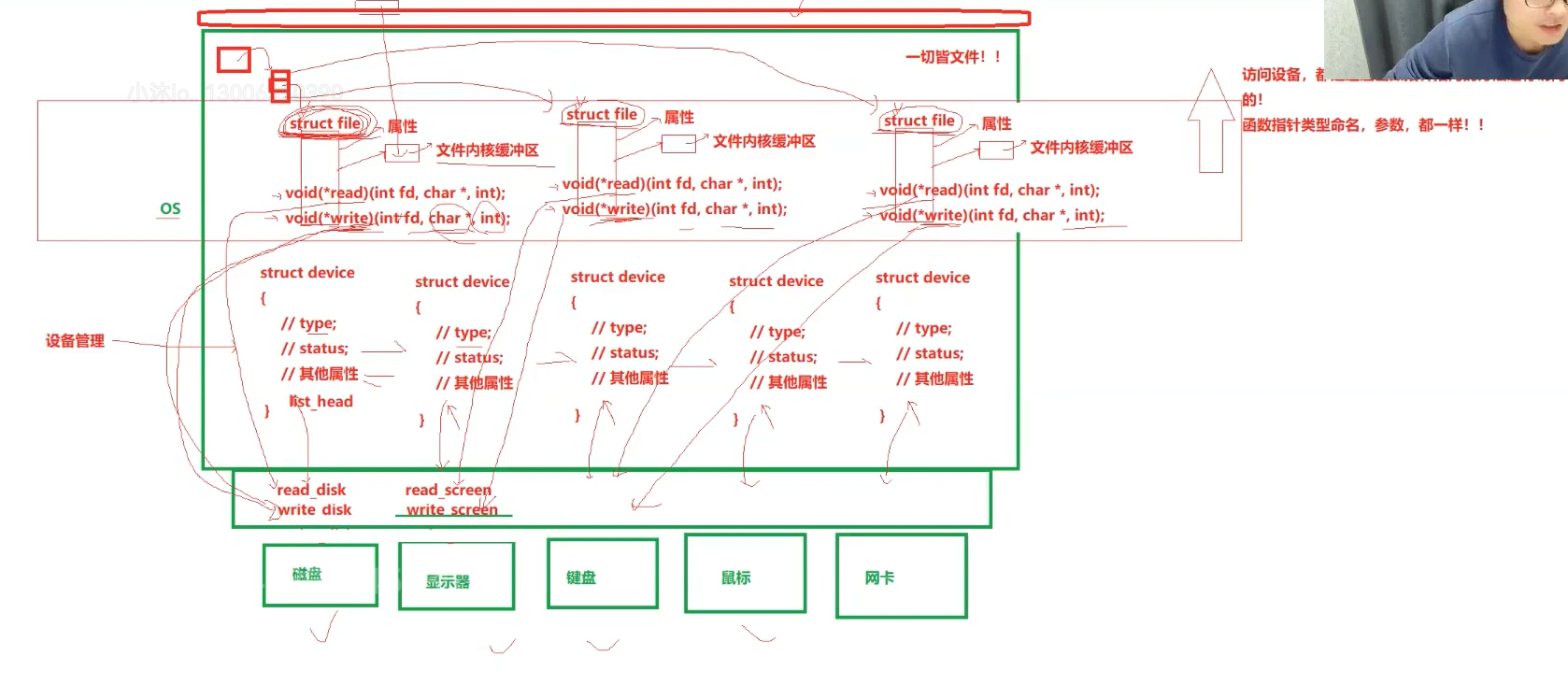

2.一切皆文件

⾸先,在windows中是⽂件的东西,它们在linux中也是⽂件;其次⼀些在windows中不是⽂件的东

西,⽐如进程、磁盘、显⽰器、键盘这样硬件设备也被抽象成了⽂件,你可以使⽤访问⽂件的⽅法访 问它们获得信息;甚⾄管道,也是⽂件;将来我们要学习⽹络编程中的socket(套接字)这样的东西, 使⽤的接⼝跟⽂件接⼝也是⼀致的。

这样做最明显的好处是,开发者仅需要使⽤⼀套 API 和开发⼯具,即可调取 Linux 系统中绝⼤部分的资源。举个简单的例⼦,Linux 中⼏乎所有读(读⽂件,读系统状态,读PIPE)的操作都可以⽤

read 函数来进⾏;⼏乎所有更改(更改⽂件,更改系统参数,写 PIPE)的操作都可以⽤ write 函

数来进⾏

之前我们讲过,当打开⼀个⽂件时,操作系统为了管理所打开的⽂件,都会为这个⽂件创建⼀个file结构体,该结构体定义在 /usr/src/kernels/3.10.0-1160.71.1.el7.x86_64/include/linux/fs.h 下,以下展⽰了该结构部分我们关系的内容:

cpp

struct file {

...

struct inode *f_inode; /* cached value */

const struct file_operations *f_op;

...

atomic_long_t f_count; // 表⽰打开⽂件的引⽤计数,如果有多个⽂件指针指

向它,就会增加f_count的值。

unsigned int f_flags; // 表⽰打开⽂件的权限

fmode_t f_mode; // 设置对⽂件的访问模式,例如:只读,只写等。所

有的标志在头⽂件<fcntl.h> 中定义

loff_t f_pos; // 表⽰当前读写⽂件的位置

...

} __attribute__((aligned(4))); /* lest something weird decides that 2 is OK

*/我们下面来看一下图,来理解一下为什么linux下一切皆文件:

1. 核心思路:用「struct file」统一封装所有资源

Linux 内核会给所有硬件设备(磁盘、显示器、键盘、网卡等) ,都套一层「struct file结构体」的壳:

- 图中 OS 层的多个

struct file,就是对应不同设备的 "文件抽象"; - 每个

struct file里包含:文件属性、内核缓冲区(用来缓存设备数据),以及 **read/write等函数指针 **(这是 "文件接口" 的核心)。

2. 设备的具体逻辑:「struct device + 硬件操作函数」

图的下层是设备管理层 和实际硬件:

struct device:对应每个具体硬件(磁盘、显示器、键盘等),记录设备的类型、状态等属性;- 硬件操作函数:比如磁盘对应

read disk/write disk(实际读 / 写磁盘的逻辑),显示器对应read screen/write screen(实际读 / 写显示器的逻辑)。

3. "一切皆文件" 的关键:函数指针绑定「统一接口 ↔ 设备逻辑」

struct file里的read/write函数指针,会绑定到对应设备的实际操作函数:

- 比如 "磁盘对应的

struct file",它的read指针会指向read disk(实际读磁盘),write指针指向write disk(实际写磁盘) - 比如 "显示器对应的

struct file",它的write指针会指向write screen(实际写显示器,也就是显示内容)

4. 用户层的体验:只用 "文件操作" 就能控制所有设备

当你在用户层调用read()/write()时:

- 不用关心操作的是 "磁盘文件" 还是 "显示器"------ 你只需要操作对应的

struct file(也就是 "文件描述符" 对应的结构体) - 内核会通过

struct file里的函数指针,自动调用对应设备的实际操作逻辑(比如写显示器就调用write screen,读磁盘就调用read disk)

Linux "一切皆文件" 的本质,是用struct file做统一抽象,通过函数指针把 "文件接口" 和 "设备的实际逻辑" 绑定起来------ 不管是磁盘、显示器还是键盘,用户都只用一套 "文件操作(open/read/write/close)" 来控制,内核帮你屏蔽了不同设备的差异。这张图正是把 "抽象层(struct file)、设备层(struct device)、硬件逻辑" 的绑定关系画了出来

3.缓冲区

1.什么是缓冲区

缓冲区是内存空间的⼀部分。也就是说,在内存空间中预留了⼀定的存储空间,这些存储空间⽤来缓 冲输⼊或输出的数据,这部分预留的空间就叫做缓冲区。缓冲区根据其对应的是输⼊设备还是输出设备,分为输⼊缓冲区和输出缓冲区

2.为什么要引⼊缓冲区机制

读写⽂件时,如果不会开辟对⽂件操作的缓冲区,直接通过系统调⽤对磁盘进⾏操作(读、写等),那么 每次对⽂件进⾏⼀次读写操作时,都需要使⽤读写系统调⽤来处理此操作,即需要执⾏⼀次系统调⽤,执⾏⼀次系统调⽤将涉及到CPU状态的切换,即从⽤⼾空间切换到内核空间,实现进程上下⽂的切换,这将损耗⼀定的CPU时间,频繁的磁盘访问对程序的执⾏效率造成很⼤的影响。

为了减少使⽤系统调⽤的次数,提⾼效率,我们就可以采⽤缓冲机制 。⽐如我们从磁盘⾥取信息,可以在磁盘⽂件进⾏操作时,可以⼀次从⽂件中读出⼤量的数据到缓冲区中,以后对这部分的访问就不需要再使⽤系统调⽤了,等缓冲区的数据取完后再去磁盘中读取,这样就可以减少磁盘的读写次数,再加上计算机对缓冲区的操作远快于对磁盘的操作,故应⽤缓冲区可极⼤提⾼计算机的运⾏速度。⼜⽐如,我们使⽤打印机打印⽂档,由于打印机的打印速度相对较慢,我们先把⽂档输出到打印机相应的缓冲区,打印机再⾃⾏逐步打印,这时我们的CPU可以处理别的事情。可以看出,缓冲区就是块内存区,它⽤在输⼊输出设备和CPU之间,⽤来缓存数据。它使得低速的输⼊输出设备和⾼速的CPU能够协调⼯作,避免低速的输⼊输出设备占⽤CPU,解放出CPU,使其能够提⾼效率⼯作

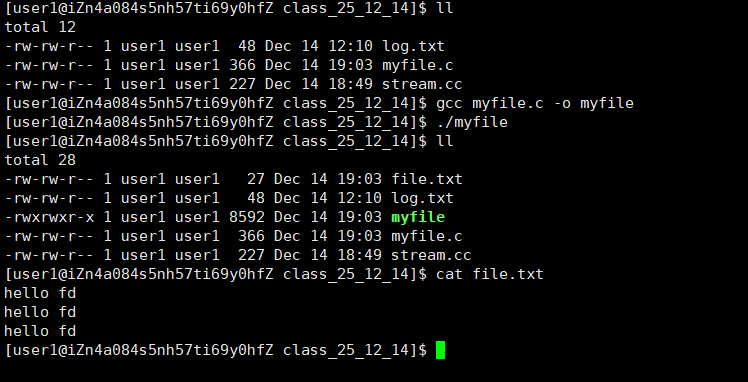

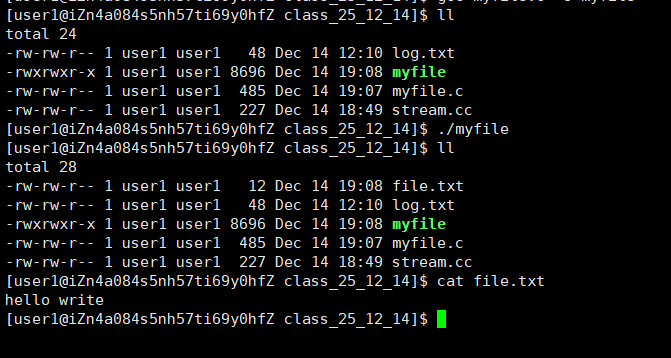

3.解决open与close问题

下面我们来看一段之前的代码:

cpp

#include <stdio.h>

#include <sys/stat.h>

#include <sys/types.h>

#include <fcntl.h>

#include <unistd.h>

int main()

{

close(1);

int fd = open("file.txt", O_CREAT | O_WRONLY | O_APPEND, 0666);

if (fd < 0)

{

perror("fd open");

return 1;

}

printf("hello fd\n");

printf("hello fd\n");

printf("hello fd\n");

return 0;

}

此时我们将内容打印到了file.txt中

要是我们关闭fd呢

cpp

#include <stdio.h>

#include <sys/stat.h>

#include <sys/types.h>

#include <fcntl.h>

#include <unistd.h>

int main()

{

close(1);

int fd = open("file.txt", O_CREAT | O_WRONLY | O_APPEND, 0666);

if (fd < 0)

{

perror("fd open");

return 1;

}

printf("hello fd\n");

printf("hello fd\n");

printf("hello fd\n");

close(fd);

return 0;

}

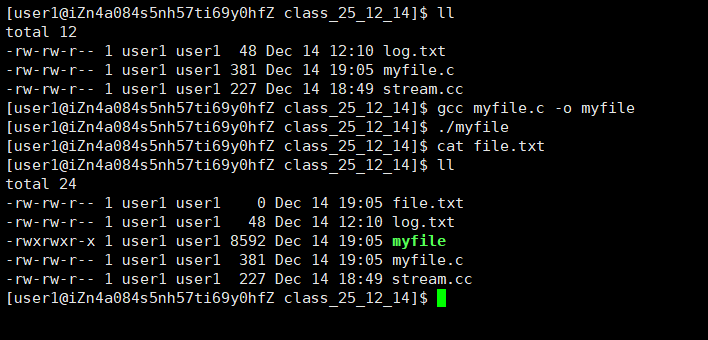

此时为什么什么都没有呢??内容去哪里啦??

先别急,如果我们在此基础上使用系统调用(write)

cpp

#include <stdio.h>

#include <sys/stat.h>

#include <sys/types.h>

#include <fcntl.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <string.h>

int main()

{

close(1);

int fd = open("file.txt", O_CREAT | O_WRONLY | O_APPEND, 0666);

if (fd < 0)

{

perror("fd open");

return 1;

}

printf("hello fd\n");

printf("hello fd\n");

printf("hello fd\n");

const char* message = "hello write\n";

write(fd, message, strlen(message));

close(fd);

return 0;

}

虽然printf的内容没了,但是write还是有的

这是因为缓冲区的存在,c语言会给我们一个缓冲区,我们会先将内容输出到c语言缓冲区,等到时机合适会将该缓冲区刷新到系统缓冲区,而write会直接将内容输出到系统缓冲区,所以会出现只要write内容,要想实现printf也输出,只需要手动刷新一下c语言缓冲区即可

cpp

#include <stdio.h>

#include <sys/stat.h>

#include <sys/types.h>

#include <fcntl.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <string.h>

int main()

{

close(1);

int fd = open("file.txt", O_CREAT | O_WRONLY | O_APPEND, 0666);

if (fd < 0)

{

perror("fd open");

return 1;

}

printf("hello fd\n");

printf("hello fd\n");

printf("hello fd\n");

const char* message = "hello write\n";

write(fd, message, strlen(message));

fflush(stdout);

close(fd);

return 0;

}

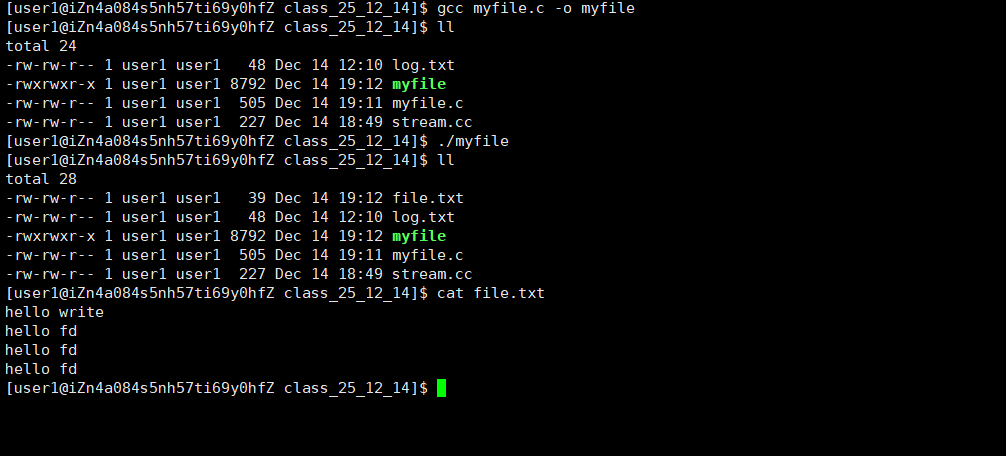

4.c语言缓冲区与系统缓冲区

可是为什么刚刚没有刷新缓冲区呢,为什么需要一个c语言缓冲区呢,下图将为你讲解:

首先需要知道,如果不要c语言缓冲区,那么printf一次,语言层就往系统层刷一次缓冲区,会极大浪费系统资源,如果我们有一个c语言缓冲区,等合适的时机在刷,就会极大降低系统负担,举个例子,你要下楼丢垃圾,你是选择一个一个丢,还是选择把垃圾装在一起丢?为了节约力气和时间,肯定选择一起丢嘛

而合适的时机是什么呢

1.强制刷新

就是fflush

2.进程退出

在main函数里面也就是return的时候

3.刷新条件满足

1.立即刷新->无缓冲->语言层输出一句话立马刷新到系统缓冲区里面

2.满了刷新->全缓冲->c语言缓冲区满了,必须要向系统缓冲区刷新了(文件用)

3.行刷新->行缓冲->一行一行从c缓冲区刷新到系统缓冲区(显示器用)

那么有了上面的基础,我们来解答一下为什么close会出现无内容的情况

很简单,因为我们先将内容放在了c语言缓冲区,此时在没有满足任何一种缓冲区刷新的情况下我们就将fd关闭,导致缓冲区内容无处可刷,所以显示无内容

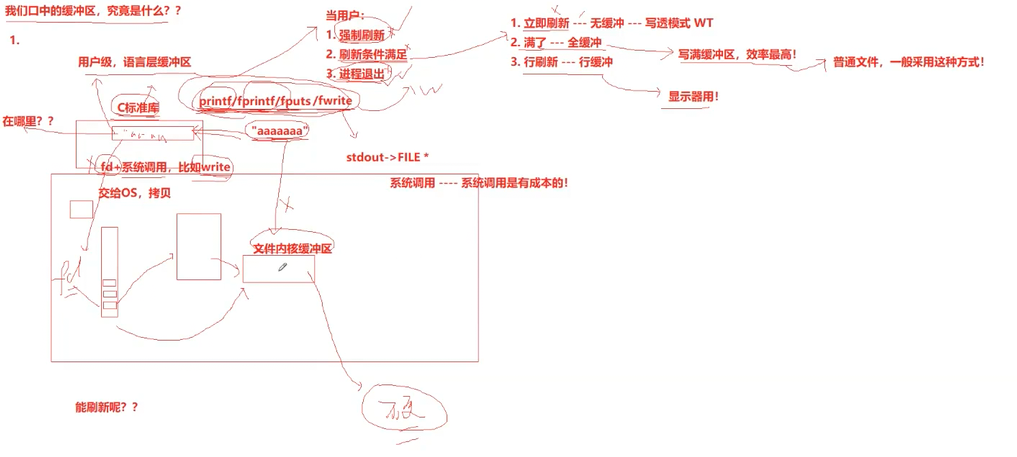

5.应用

cpp

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <unistd.h>

int main()

{

//语言层调用

printf("hello printf\n");

fprintf(stdout, "hello fprintf\n");

const char* message1 = "hello fwrite\n";

fwrite(message1, strlen(message1), 1, stdout);

//系统层调用

const char* message2 = "hello write\n";

write(1, message2, strlen(message2));

fork();

return 0;

}

为什么两个答案不一样呢?

我们先来看看第一个直接使用,因为我们前面讲过,显示器是行刷新,所以我们一行一行刷新,fork的子进程与父进程缓冲区都是空的,所以只有四个输出

第二个重定向操作后,就从显示器刷新变味了文件刷新,也就是全缓冲,此时父进程缓冲区是语言层的三个输出,fork之后的子进程会拷贝一份父进程pcb,包括缓冲区,所以此时进程结束两个进程刷新缓冲区,就出现了两分语言层输出,而write是系统调用,所以直接输出到系统缓冲区,只有一个

4.简单的libc编写

Makefile:

cpp

code : mystdio.c usercode.c

gcc $^ -o $@

.PHONY : clean

clean :

rm -f codemystdio.h:

cpp

#pragma once

#include <stdio.h>

#define MAX 1024

//刷新方式

#define NONE_FLUSH (1 << 0)

#define LINE_FLUSH (1 << 1)

#define FULL_FLUSH (1 << 2)

typedef struct IO_FILE

{

int fileno; //文件描述符

int flag; //标志位

char outbuffer[MAX]; //缓冲区

int bufferlen; //缓冲区元素个数

int flush_method; //刷新方式

}MyFile;

MyFile* MyFopen(const char* path, const char* mode);

void MyFclose(MyFile*);

int MyFwrite(MyFile* , void* str, int len);

void MyFFlush(MyFile* );mystdio.c:

cpp

#include "mystdio.h"

#include <sys/types.h>

#include <sys/stat.h>

#include <fcntl.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <unistd.h>

static MyFile* BuyFile(int fd, int flag)

{

MyFile* f = (MyFile*)malloc(sizeof(MyFile));

if (f == NULL)

{

return NULL;

}

f->bufferlen = 0;

f->fileno = fd;

f->flag = flag;

f->flush_method = LINE_FLUSH;

memset(f->outbuffer, 0, sizeof(f->outbuffer));

return f;

}

MyFile* MyFopen(const char* path, const char* mode)

{

int fd = -1;

int flag = 0;

if (strcmp(mode, "w") == 0)

{

flag = O_CREAT | O_WRONLY | O_TRUNC;

fd = open(path, flag, 0666);

}

else if (strcmp(mode, "r") == 0)

{

flag = O_RDONLY;

fd = open(path, flag);

}

else if (strcmp(mode, "a") == 0)

{

flag = O_CREAT | O_WRONLY | O_APPEND;

fd = open(path, flag, 0666);

}

else

{

//TODO

}

if (fd < 0)

{

return NULL;

}

return BuyFile(fd, flag);

}

void MyFclose(MyFile* file)

{

MyFFlush(file);

}

int MyFwrite(MyFile* file, void* str, int len)

{

//拷贝

memcpy(file->outbuffer + file->bufferlen, str, len);

file->bufferlen += len;

//行刷新

if ((file->flush_method & LINE_FLUSH) && file->outbuffer[file->bufferlen - 1] == '\n')

{

MyFFlush(file);

}

return 0;

}

void MyFFlush(MyFile* file)

{

if (file->bufferlen == 0)

{

return;

}

int n = write(file->fileno, file->outbuffer, file->bufferlen);

(void)n;

file->bufferlen = 0;

}usercode.c:

cpp

#include "mystdio.h"

#include <string.h>

#include <unistd.h>

int main()

{

MyFile* filep = MyFopen("./log.txt", "a");

if (!filep)

{

perror("filep open\n");

return 1;

}

//char* message = (char*)"hello my_libc\n"; //带/n行刷新

char* message = (char*)"hello my_libc!!!"; //不带就是全刷新

//MyFwrite(filep, message, strlen(message));

int cnt = 10;

while (cnt--)

{

MyFwrite(filep, message, strlen(message));

printf("filep->outbuffer : %s\n", filep->outbuffer);

sleep(1);

}

MyFclose(filep);

return 0;

}